Each year in August, researchers, librarians, educators, students, and open access advocates gather together for the FORCE11 Scholarly Communication Institute (“FSCI”)—a jam-packed week of learning, discussion, and celebration of all aspects of scholarly communication. This year, I was lucky enough to be one of them—thanks to a generous travel scholarship. The experience was one I’ll never forget.

Over the course of the week, I had the chance to learn from an incredible community of people. I heard from librarians, publishers, and researchers about their changing role within scholarly communication and the challenges and opportunities that come with it. I gained perspectives from Mexico, Japan, Sudan, and beyond about the unique state of scholarly communication in each of these nations. I took part in conversations about open knowledge, open pedagogy, and open culture, as well as the many different forms these ideas can take.

I left FSCI2019 with many answers, but also with many questions. I’m summarizing just a few of them here for those who couldn’t attend in person:

Is “access” to knowledge enough?

What audiences are overlooked by ‘traditional’ scholarly publishing models? Does making research available actually make it accessible? And how do factors like geography, culture, infrastructure, and education influence who has access to knowledge and who doesn’t?

These questions came up again and again in all of my courses, as well as in many of the lightning talks and plenaries. Presenters highlighted the importance of offering educational materials in multiple languages, depositing publications in open repositories, writing for non-academic audiences, and more.

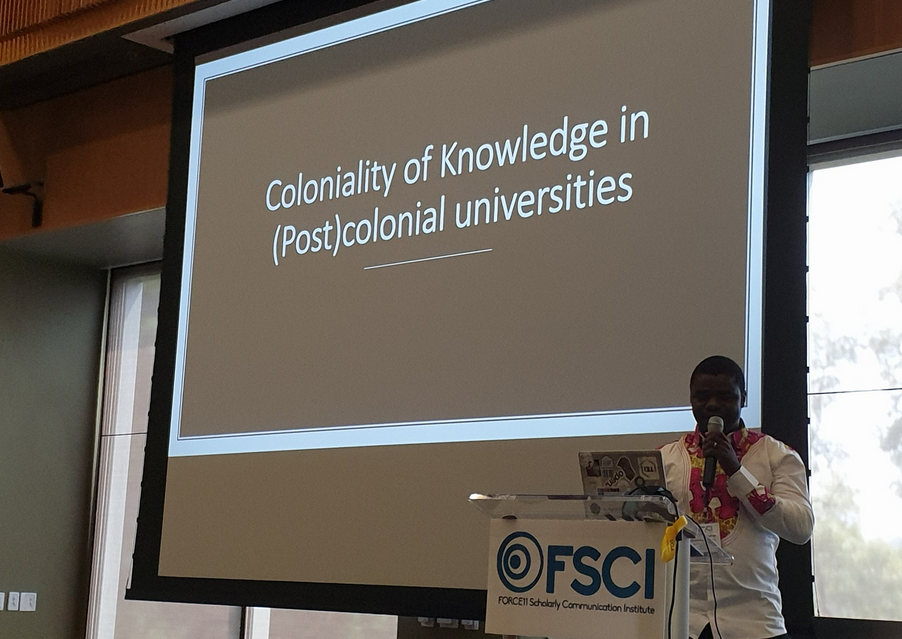

But what struck me most was Thomas Hervé Mboa Nkoudou’s plenary keynote, “Scholarly Communication reimagined from Post Colonies.” During the talk (and, later, in his class on the same subject), he emphasized how contemporary academic publishing keeps researchers in the so-called ‘Global South’ at the periphery of research production. Highlighting the colonial nature of scholarly communication, he pushed us all to reconsider our own roles as producers, consumers, and disseminators of knowledge:

“We should explore alternative ways for communicating research, aside from a traditional, published journal article.” —Thomas Hervé Mboa Nkoudou

What does the scholarly future look like?

The changes undergoing academic publishing were another key topic of conversation at FSCI this year. Should we ‘open’ up the peer review process or abandon it entirely? Is the preprint a viable alternative to a scholarly journal article? How do traditional publishing frameworks disadvantage early career researchers?

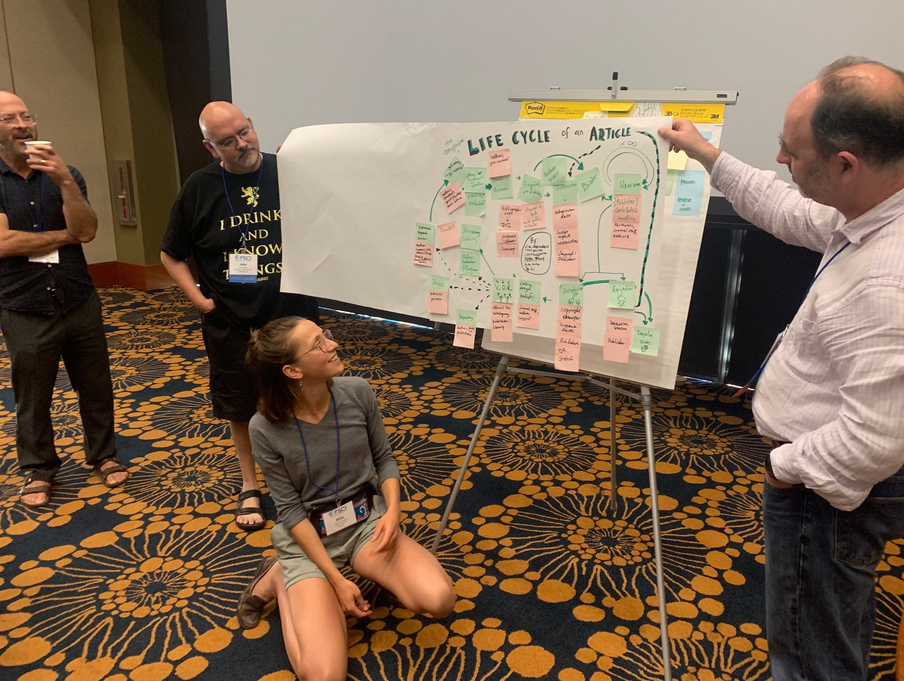

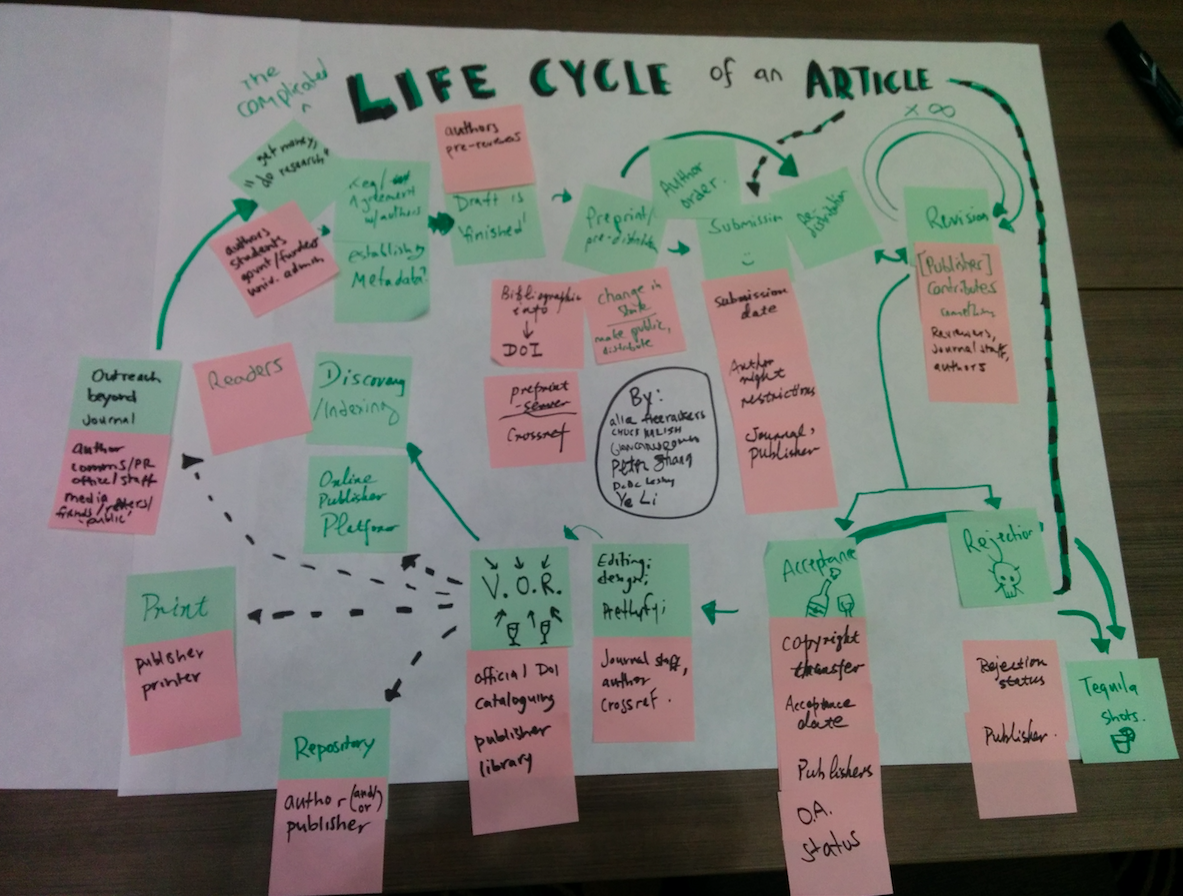

Questions such as these sparked fascinating conversations, especially in Cameron Neylon and Nicky Agate’s course, Inside Scholarly Communication Today. Through hands-on activities and lots of group discussion, we dug deep into the current nature of scholarly publishing—and brainstormed some creative ways it could be improved.

Can we build a scholarly communication system on collaboration, rather than competition?

How did a system meant to encourage sharing and collaboration become obsessed with maintaining power and prestige? Is a more open, inclusive approach to scholarly communication even possible? What would that mean for science—not to mention society?

From the classroom to the dinner hall, countless conversations centered on the rivalry that permeates so much of academic life. We discussed everything from peer-review sabotage to scholarly superiority complexes, brainstorming ways to prevent them. We daydreamed about the possibility of creating a more “generous” academic system—one built on trust and mutual support, rather than competition.

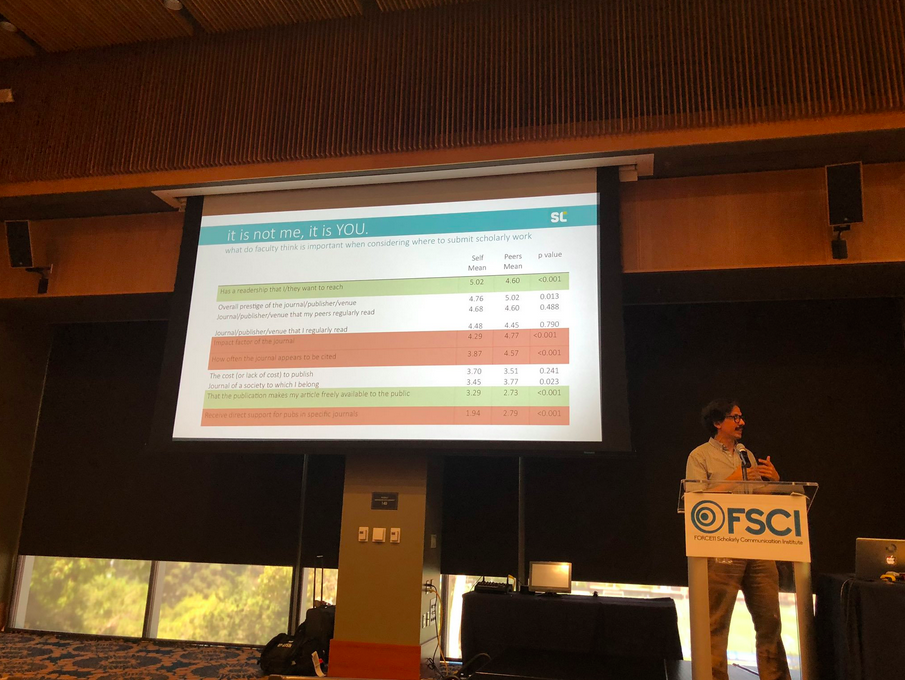

The final talk of the week—by the ScholCommLab’s own Juan Pablo Alperin—ended these conversations on a more positive note. Citing recent research about how faculty perceive their professional futures, he shared that many academics really do value openness, but feel pressured to pursue prestige-oriented publishing strategies because of what they think their peers value. This research wasn’t new to me, but I saw it in a new light after everything we’d covered during the previous sessions.

“No problem is too big, but every problem is too big if you constrain how you think”— Anita Bandrowski

As we wrapped up the closing remarks, I was reminded of something Anita Bandrowski said during one of the earlier presentations: “No problem is too big, but every problem is too big if you constrain how you think.” When it comes to changing our academic system, we still have a long way to go. But if we can address our misconceptions and be honest about what we truly value, change really is possible.

Find out more about the FORCE11 Scholarly Communication Institute on their website.