Altmetrics researchers: Time to take another look at Facebook, you’ve been missing something

“I hope that the kind of altmetrics research that has been going on lately is dying out,” says Asura Enkhbayar, in a conversation about the ScholCommLab’s latest preprint. “It is time to move beyond crunching numbers of whatever is easiest and to look for the activity we care about on social media.”

The preprint—which he published last week with Stefanie Haustein, Germana Barata, and Juan Pablo Alperin—investigated how much of research shared on Facebook is hidden from public view. Although wishing some altmetrics research “dead” may be a little strong, the results show that there are important questions that have been overlooked by the altmetrics community.

In this blog post, we highlight key findings from the study and what they mean for scholarly communications and altmetrics research.

A long-overlooked platform

“Facebook has often been disregarded in altmetrics research,” Asura says. “It is seen as a platform that doesn’t produce real engagement with science.”

Previous studies have found that less than 8% of recent research is shared on the platform. This number is much lower than what is found on Twitter—a platform with a fraction of the number of users. As a result, many researchers avoid studying Facebook altogether, despite its massive user base.

But, as the team’s research reveals, Facebook’s “low” levels of engagement may have less to do with the platform itself, and more to do with how the data is collected.

“[Companies like] Altmetric only collect mentions of research that happen in Public Pages,” Juan explained in a recent Twitter thread. “This misses every time your friend, cousin, mom, or whoever posts a link on their Timeline!”

A novel approach to tracking research on Facebook

To capture these “invisible” research mentions, the team decided to try a different approach—one based on querying the API, rather than data mining.

“Companies like Plum Analytics use a similar approach” Asura says, “but we decided to take things further by looking at many different links URLs where the research article can be found.” He continues: “Science does not live in one place; there’s preprints, postprints, different variations—and we needed to capture engagement with as many of them as possible.”

“Science does not live in one place; there’s preprints, postprints, different variations—and we needed to capture engagement with as many of them as possible.”—Asura Enkhbayar

This new technique complicated things considerably (so much so that the team ended up publishing a whole other article about the challenges involved). But it had the benefit of allowing the team to collect and consolidate the many different online versions of research shared on Facebook. Plus, it allowed them to explore—for the first time—research shared in Closed Groups, Timelines, and other private spaces inside Facebook.

More than half of research shared on Facebook is “invisible”

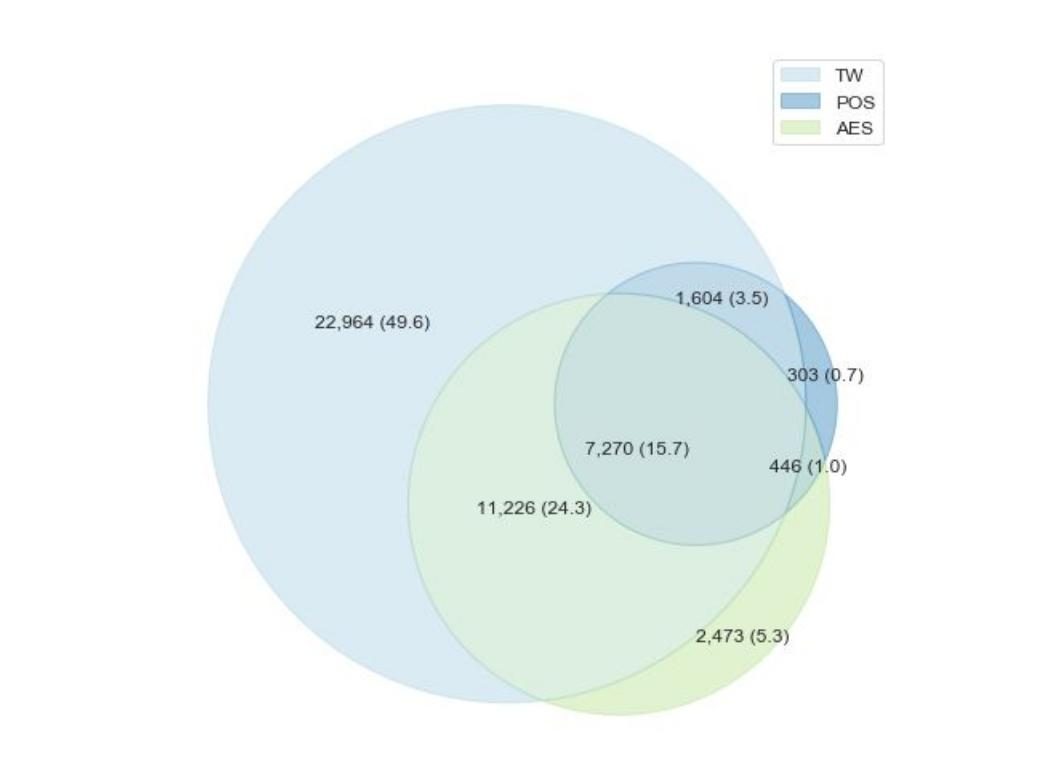

Using this approach, the team identified an additional 13,699 research articles (58.7%) not found by Altmetric’s method. In other words, although many Facebook users share research papers publicly, the majority prefer to do so in private exchanges—hidden from public view.

Even more importantly, the research papers that are shared on the platform receive almost as much engagement as those on Twitter.

“The volume of the engagement—how many times a paper is shared—is actually comparable between the two platforms,” Asura explains. “It’s fascinating; papers that receive a lot of engagement from audiences behave similarly to those on Twitter.”

Facebook users may not share quite as many academic papers as Twitter users do. But these findings suggest they’re much more interested in research than previously thought.

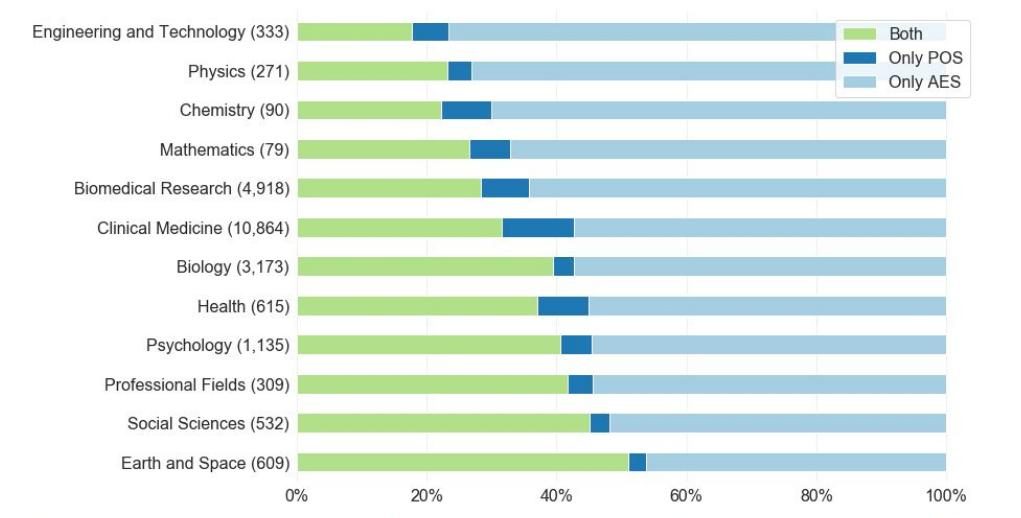

Finally, the team also found some large disciplinary differences in the data. Papers in the so-called “hard sciences” were at a greater disadvantage when measured by public posts than those in other disciplines. In other words, public shares, the most-used Facebook altmetric, seems to have a disciplinary bias:

Reimagining the future of Facebook altmetrics

What do these findings mean for the future of altmetrics research? Context, Asura says, is key.

“I can’t overemphasize how important it is to think critically about this data,” Asura says. “To consider how it applies to our work and how it impacts people outside of the Western world.”

Twitter may be the top platform for many academics, he explains. But Facebook remains one of the most important social media platforms for more than 2 billion active monthly users—especially those based in the Global South, beyond the traditional centers of knowledge production.

“Sure, looking at Facebook engagement is messy and complicated,” Asura says. “But if we truly care about the public’s interest in research, we need to look beyond that.” He continues: “It’s time we examine this platform in a more critical way.”

To find out more about the study, check out the preprint on arXiv.