Preprint comments: A place for praise, critique, and everything in between

Once all but unknown to anyone but economics or high energy physics researchers, preprints are becoming more popular across the disciplinary spectrum. These unreviewed reports allow scholars to share their work with the wider research community as soon as it is finished, without having to navigate what can sometimes become a lengthy peer review process. This ability to receive almost-instant feedback may be the preprint’s greatest strength — or, at least, it could be, if we knew that this feedback process were truly taking place. Until recently, no one had ever systematically analyzed whether preprint server comment sections contain useful commentary of any kind.

That’s where new research by Mario Malički, Joseph Costello, Juan Pablo Alperin, and Lauren Maggio comes in. The study, which is (appropriately) available in preprint, collected all comments posted to bioRxiv preprints between May 2015 and September 2019. The team filtered this data set to include only the comments that had not received any replies, then carefully read and classified them. For each of the almost 2000 comments, they assessed whether the commenter was an author of the preprint or someone else. They also analyzed the text itself, categorizing it as a praise, critique, question, or something else entirely.

In this interview, Mario shares key insights from the study, touching on peer review reports, compliment sandwiches, and everything in between.

Why was it important to look at preprint comments?

I think the biggest criticism about preprints has been the fact that they are not peer reviewed. Comments could potentially be a way to deal with that criticism, as they enable other scholars to look at what other researchers have said about it.

When you were analyzing these comments, did you find any evidence of that actually happening — of people reviewing preprints?

For me, there were two big surprises in this study. The first was that a lot of the comments (31%) were actually made by the authors themselves. I would have thought that all of the author comments would be replies to other comments on certain aspects of the preprint.

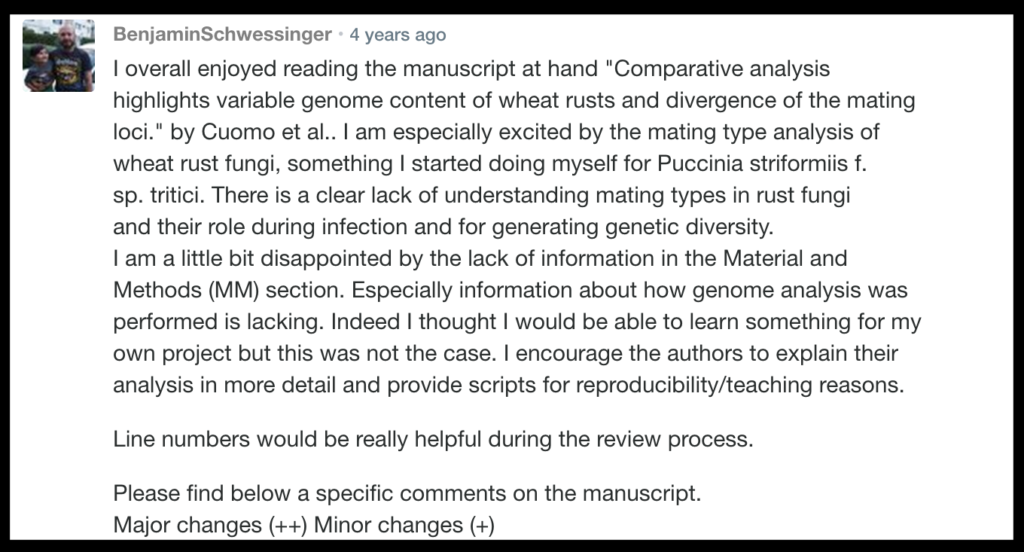

The second surprise was that 12% of comments were full peer review reports. I thought that the majority of people would write maybe one or two comments or just a simple question, but there were full peer review reports in our sample, which was very nice to see. I think that shows how people approach things. As a commenter, you have a choice: Will you ask all the questions at once — everything that bugs you — or are you just going to ask the one thing that intrigues you? We found evidence of both of those practices.

When you say commenters were posting full peer review reports, what did that actually look like?

To me, they look exactly like the ones that I get when I invite experts to review papers for my journal. They usually start with “Dear authors, thank you for the opportunity to look at your paper. I found it interesting but there are some things that I would like to address.” Then they typically create a list of bullet points to raise more issues, and add something like, “Hopefully this will help you make your paper better.”

Basically, it’s a compliment sandwich.

He he, yes. We actually found the compliment sandwich in a lot of all our comments. Sometimes in the full peer review reports, and sometimes they were just included in a question or two. Around 50% of those less formal comments had little positive comments mixed in between criticisms or questions. Maybe it’s just the way that we communicate: first a little praise, and then attack.

“We actually found the compliment sandwich in a lot of our comments… Maybe it’s just the way that we communicate: first a little praise, and then attack.”

Mario Malički

Tell me more about those more casual one-off comments—the other 88% of your sample. What did those look like?

We found all sorts of things. There would sometimes just be a simple “thank you.” But there were also questions from patients about diseases that they had that the paper was dealing with, or mentions along the lines of, “We did a similar study, you might be interested in it.” Then there were questions like, “I see maybe a problem in your figure. Am I interpreting this right?” Or, “Do you know if anyone else is working on this?” Or, “What happens next?”

When we classified them, the majority of these non-author comments were either suggestions or criticisms. We did not, however, count how many different critiques or how many different questions they raised. Still, it was interesting to see that, even in these comments that were not full peer review reports, there were lots of readers providing feedback or critique on a specific aspect of the preprint.

What’s the main takeaway of this research for the scholarly community?

It’s a tricky one to answer, because we looked at just those preprints that had received only a single comment. Sixty percent of those we analyzed were comments not by the authors but by someone out there commenting on the paper. None of them got a reply, but none, to us, looked like comments that couldn’t be replied to.

Now, we know that bioRxiv doesn’t prompt authors when a comment has been made to their preprint, so it is possible that authors were maybe not aware of the comments that were raised. But I think it may be a similar situation as the one we find with platforms like PubPeer, where anyone can comment on papers after they’ve been published in a journal. We know from these platforms that often authors will not reply. Of course, there is no international law or regulation that forces you to reply to a critique or even a question that someone raises out there in the world. You have no obligations, except maybe your own personal interest. But I’m always thinking that, if it was me, I would want to try to answer.

Do you think we can improve comment sections? It sounds like there’s potential for some really meaningful conversations to take place there.

Yes, I really think there is. Maybe the corresponding author should get at least an option to receive some sort of notification when a comment is made to their preprint. Because I feel that, unless this is done, people may stop using this public platform to reach authors; they will just write a personal email instead. While a personal email may be beneficial to you—the person who asked the questions—it’s only when the public can see your questions that others can benefit from them, too.

While a personal email may be beneficial to you—the person who asked the questions—it’s only when the public can see your questions that others can benefit from them, too.

Mario Malički

In another (upcoming) study, we actually found that 70% of all preprint servers have comment sections. But none of these servers have yet come out with studies on the frequency of use, the outcomes, or what the users want. So I think that we need a little bit more research. We need to see, in the long term, how sustainable preprint server comment sections are and how their role in scholarly publishing might evolve. There is more research coming out on the effects of open peer review in scholarly journals, and more and more journals embracing open review practices. As comments, in a way, resemble open scholarly communication, I expect we will see both more research and more use of public commenting in the near future.

For more information, check out the Preprints Uptake and Use Project Page or read the full preprint at bioRxiv.