Publish or perish? Faculty publishing decisions and the RPT process

By Meredith T. Niles, Lesley Schimanski, Erin McKiernan, and Juan Pablo Alperin – with Alice Fleerackers

As tenured faculty positions become increasingly competitive, the pressure to publish—especially in “high impact” journals—has never been greater. As a result, many of today’s academics believe having a strong publication record is necessary for the review, promotion, and tenure (RPT) process. Publishing, for some, has become synonymous with professional success.

Yet little is known about academics’ perceptions of the RPT process and how they influence their publishing decisions. What research outputs do faculty believe are valued in RPT decisions? How do these beliefs affect where and what they publish?

To find out, we surveyed faculty of 55 academic institutions across the US and Canada, asking them about their own publishing priorities and those of their peers, as well as their perceptions importance within review, promotion, and tenure. Here’s what we found:

Faculty prioritize journal readership in publishing decisions…

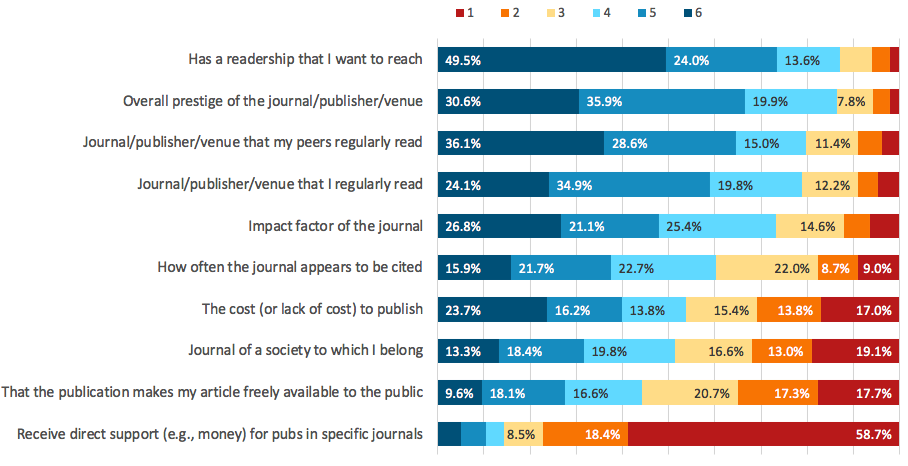

When it comes to deciding where to publish their work, academics reported valuing journal audience above all other factors. The top three factors they identified were:

- Whether the journal had a readership they wanted to reach

- The overall prestige of the journal

- Whether the journal was regularly read by their peers

Of course, other factors, like the journal’s impact factor (JIF) or the fees associated with publication, were still important to many faculty, but to a lesser degree than readership:

Importantly, we saw some significant demographic differences among faculty in their publishing priorities. Non-tenured respondents—who are under greater pressure to perform than tenured faculty—placed higher importance on the JIF, for example. Younger faculty were also more likely to prioritize factors like journal citation frequency and journal prestige, compared to older, more established peers.

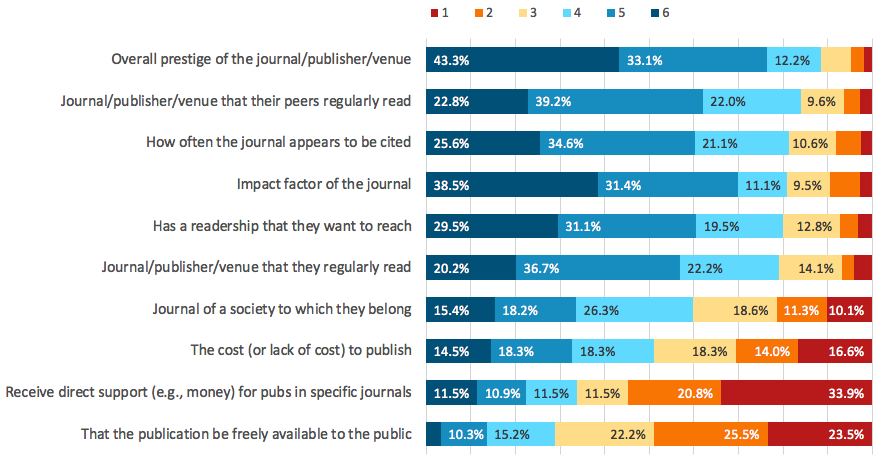

…but faculty believe their peers value prestige above all else.

When it came to evaluating others’ publishing priorities, however, faculty responded quite differently. They believed their peers would be more likely to value factors like journal prestige and JIF when deciding where to publish their work. They also believed their peers would be less likely to make decisions based on the journal’s readership or open access status:

This sense of illusory superiority when comparing oneself to peers is nothing new, but it was interesting to see it come into play in our survey.

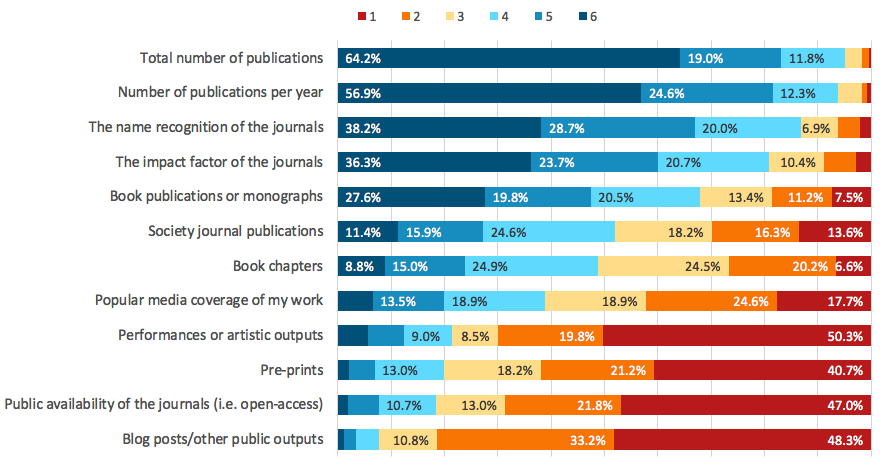

Academics see publication quantity and journal reputation as top factors in RPT decisions

Next, we asked faculty what factors they believed were valued most during the RPT process. We found a notable disjoint between their own publishing priorities and what they felt would benefit their careers.

Faculty identified the following three factors as being most important for RPT decisions:

- Total number of publications

- Number of publications per year

- Journal name recognition

Again, there were important demographic differences among faculty, with older, tenured respondents—those most likely to serve on RPT committees—being were less likely to value journal prestige and publishing metrics, compared to untenured respondents.

Faculty’s beliefs about the RPT process are key to their publishing decisions

Finally, we explored how academics’ perceptions of the RPT process affected their own publishing priorities through a series of models. In short, we found that these perceptions of what is valued by the RPT process were more likely to predict publication decisions than age, gender, or publication history.

Conclusion

Together, these results paint a complex picture of the pressures faculty face when deciding where to publish their work. On the one hand, most academics value the readership of a journal over its citation metrics. Yet, this value is at odds with the factors they believe will help them succeed in the RPT process—publication quantity and journal reputation—even though tenured faculty and those often on RPT committees didn’t value these factors as highly. Adding to this are the disjoints between faculty’s own publishing priorities and how they perceive those of their peers. Such disjoints highlight clear pathways for conversation in academia about what is most valued by communities for their scholarship, conversations we hope this work can help facilitate.

The results of this survey build on previous work examining the role of public scholarship and the journal impact factor in RPT documents. Read the full preprint at bioRxiv, or find out more about the RPT Project on the scholcommlab website.

7 Comments

Comments are closed.

[…] From a Scholcomm Lab Blog Post: […]

[…] own Juan Pablo Alperin—ended these conversations on a more positive note. Citing recent research about how faculty perceive their professional futures, he shared that many academics really do value openness, but feel pressured to pursue […]

[…] when we surveyed faculty about how they choose where to publish, we found that researchers are motivated first and foremost […]

[…] all the critiques of publish-or-perish culture, the pressures to publish keep […]

[…] This was a closing keynote address by Prof Juan Pablo Alperin of ScholCommlab where he unveiled interesting discoveries about what faculty believe others think about them regarding their open science practices. The keynote focused on findings from his research which revealed that the current system encourages continuous patronage of perceived high impact journals at the expense of making research open. Although faculty are interested in open access publishing, their decisions are constantly influenced by what their peers think, and they value prestige above all else. Hence, would including open scholarship in faculty promotion make open access publishing a reality? For more information on this interesting topic, you can read his full article here. […]

[…] to readership, faculty cared about journal prestige and journals which their peers read. As for the RPT process, faculty thought they would be evaluated based on publication quantity and prestige—but this […]

[…] This was a closing keynote address by Prof Juan Pablo Alperin of ScholCommlab where he unveiled interesting discoveries about what faculty believe others think about them regarding their open science practices. The keynote focused on findings from his research which revealed that the current system encourages continuous patronage of perceived high impact journals at the expense of making research open. Although faculty are interested in open access publishing, their decisions are constantly influenced by what their peers think, and they value prestige above all else. Hence, would including open scholarship in faculty promotion make open access publishing a reality? For more information on this interesting topic, you can read his full article here. […]