Would including open scholarship in tenure guidelines move the needle?

Keynote presented by Juan Pablo Alperin at FSCI on August 9, 2019.

Overview

- Introduction

- The case for open access

- Barriers to open access

- The role of incentives

- What do we know about incentives?

- The Review, Promotion, and Tenure project

- Digging further into open access

- What do the RPT documents ask for?

- What are we to make of all this?

Introduction

Before we begin, I would also like to acknowledge that much of the work I am going to be drawing upon here today is made possible by the incredible team at the Scholarly Communications Lab. For those that don’t know, the ScholCommLab is a research group I co-lead with Stefanie Haustein from the University of Ottawa. I have the privilege of having a small team of people work with me on all kinds of problems related to scholarly communication, and having them around makes everything I do better. I know these thank yous typically go at the end, but I like to give them at the beginning when everyone is still paying attention.

More specifically, I need to thank and acknowledge the team behind the review, promotion, and tenure project, which includes Erin McKiernan, Meredith Niles, and Lesley Schimanski, who have led this project as much as I have, as well as several Research Assistants who have contributed significantly. It is all too easy to be the one who gets to stand here and take credit, but it is a credit that I need to share with all of them.

And finally, before I really get going, I feel compelled to disclose that much of what I am going to present today is very US- and Canada-centric. For those of you who are familiar with me and my work, you will know that I am typically the first to call out these Northern views. To this, I can say two things. First, I live and work in Canada, and it is in part because of the incentives in my own academic career that I do research that is not centered on Latin America—so think of this as part of the takeaway from today’s talk. As I will discuss, the pressure to research the Global North is not just an issue of promotion and tenure; rather, the whole system is set up to make it easier for me to get funding, collaborate, and publish about “global” research. Second, in my defense, I do think that those of you who are not working within this context will still find value in what I will share today. There are a lot of lessons about human nature in what we found—about what drives us and about the tricks we play on ourselves—that I do not think are specific to these two countries. I would love to hear if you agree.

Finally—and I promise, this is the last thing before I really get going—a warning: This talk may look like it is going somewhere depressing, but it is not. It ends with what I think is a fundamentally positive story of where we may be headed and what we might do to bring about change. To move the needle, if you will.

I both want to start and finish today by asserting that those of us who work in academia—faculty and librarians alike—generally share some underlying values that society is best served when research and knowledge circulate broadly. Yet, although I think we very likely already agree on these as a community, we have certainly spent a lot of time and energy justifying why we should have more open scholarship—specifically open access.

As some of you may remember, in earlier days, the idea of OA was seen as somewhat radical. It was viewed as something that faculty needed to be convinced of—not because they disagreed with sharing knowledge, but because the more formal notion of OA was new, and OA journals had not been around long enough to demonstrate their value.

The case for open access

Correspondingly, a lot of effort has gone into justifying the need for OA, including arguments for all of the following:

- citation advantage for authors: the idea that publishing OA leads to more citations

- ethical imperative: that it’s the right thing to do

- economic necessity: that it eases the financial burden on university budgets

- responsibility to tax-payer: that those who pay for research deserve access to it

- accelerated discovery: that easier access and fewer restrictions means faster science

- contribution to development: that OA, by bridging key knowledge divides, can help guide development

- and more…

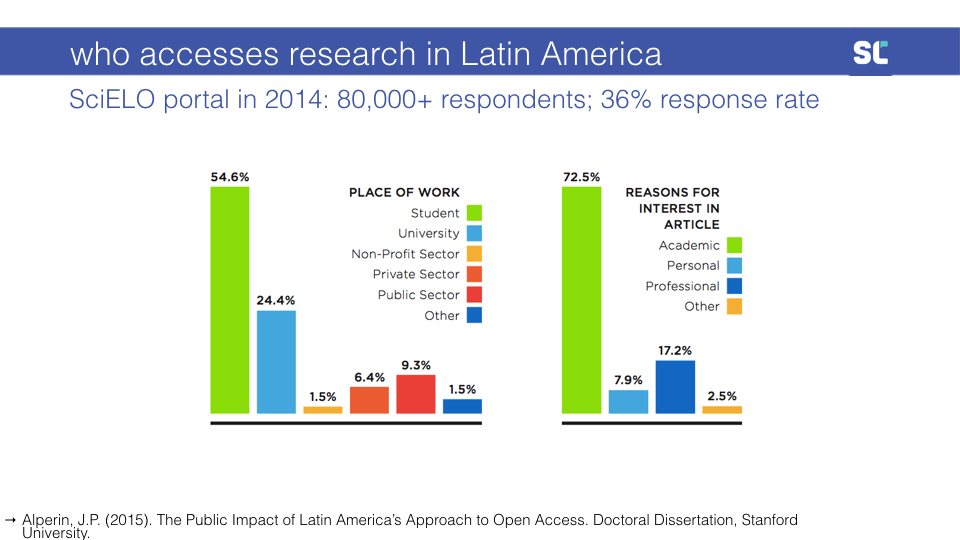

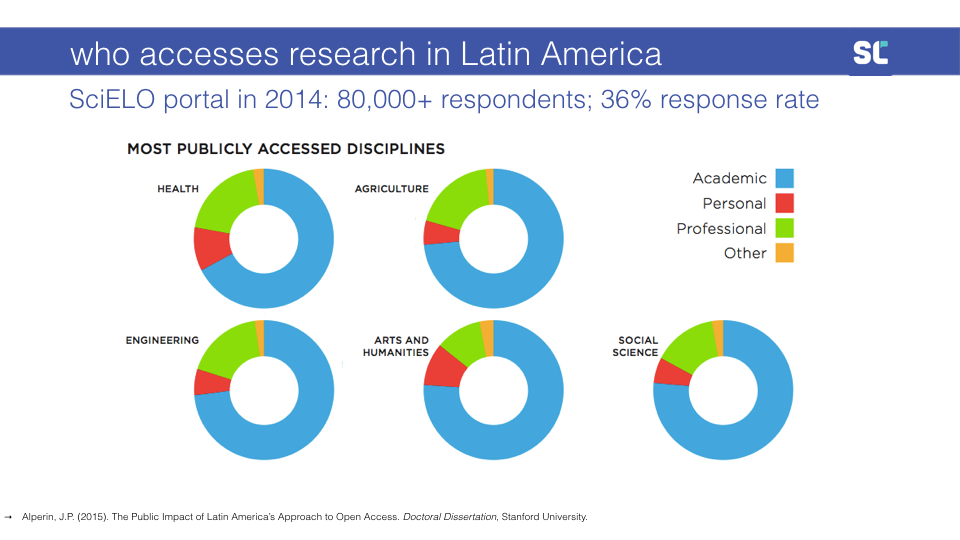

In my own work—and bringing it back to the case of Latin America—I ran a series of micro-surveys on one of the largest journal publishing portals in the region and found that between one fifth and one quarter of downloads of research articles came from outside of academia. That number varied a little depending on how exactly I asked the question. But, as you can see, students made up a significant portion of the downloads, whereas faculty (people working at universities) only made up a quarter. When I asked the question a different way, I found that around a quarter of the downloads came from people interested in research for reasons other than the academic one. While students and faculty make up about three quarters of the use, you’ll see that the public is also interested.

What is interesting is that this public demand—what I call Public Impact—is not limited to those fields where we would expect there to be public interest. Yes, when we look across disciplines, Health and Agriculture have the greatest non-academic interest, with a high proportion of that coming from those accessing for professional reasons. But we also find evidence of public impact in the Arts and Humanities—with a pretty even split between personal and professional interest—and in the Social Sciences—with more professional interest than personal.

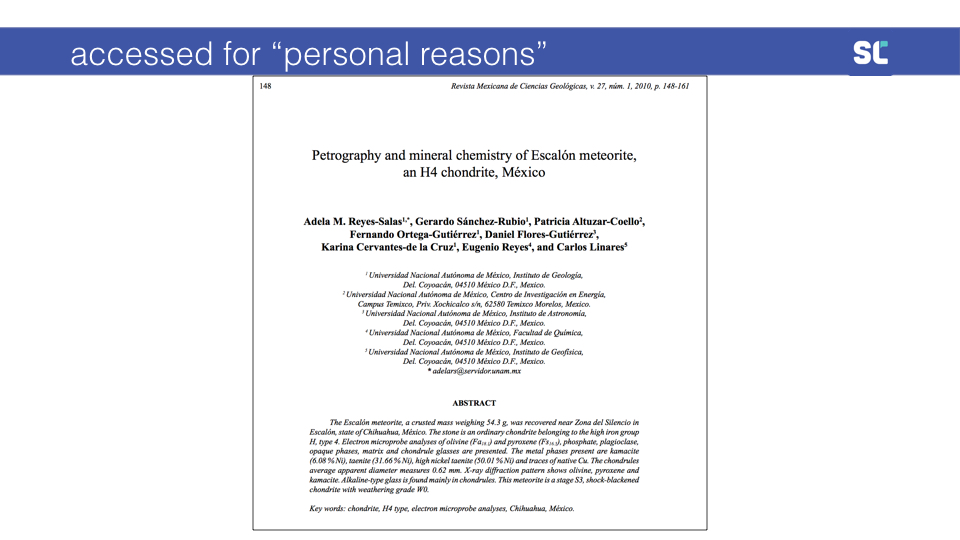

Let me show you just a couple of the papers for which there was reported “personal interest”:

In case you cannot read that, this paper is titled Petrography and mineral chemistry of Escalón meteorite, an H4 chondrite, México:

And one more, for good measure:

I cannot even pronounce the title of this paper, yet people access it for personal reasons.

So while I welcome efforts to translate and communicate science—which are important for all kinds of reasons—examples like this show that all research can have a public audience.

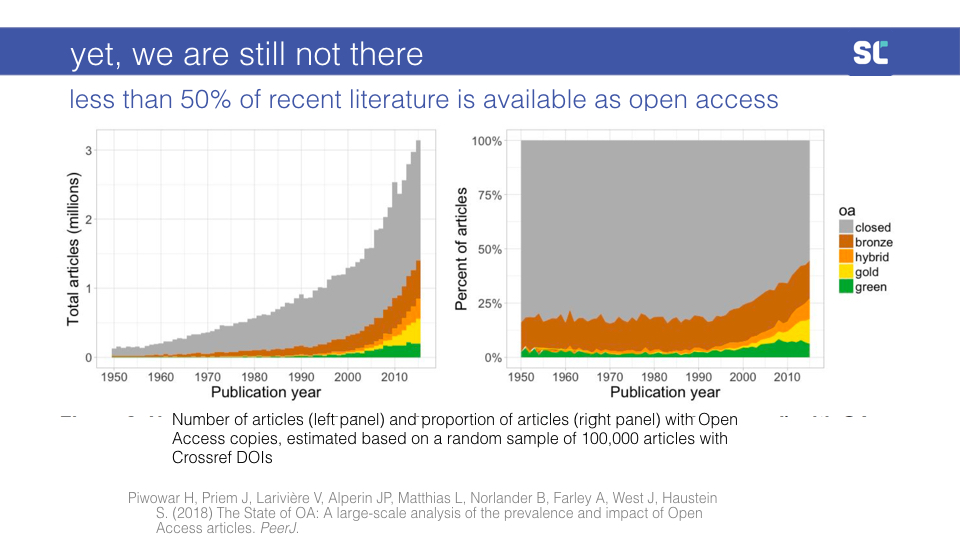

And yet, we are still not there. In 2018, we did a study using a tool and database called Unpaywall, and found that only 45% of the most recent literature is freely available to the public. This number is growing, both in the absolute number and as a percentage of total publications. But, still, we are barely making half of our publications publicly available.

Barriers to open access

We have plenty of evidence that the public values research that has been made open. We have even more compelling evidence that academics need and value access. So, shouldn’t we value providing that access?

Obviously, the reasons for why we do not have access are complex. They are social, individual, and structural at the same time, and they also have a technical component. As with any complex social system, these barriers are also deeply intertwined with one another.

One such narrative goes as follows:

- subscription publishing is very profitable

- alternative models are less so

- many established journals rely on subscriptions

- there are increasing pressures to publish more

- nobody has time for careful evaluation

- reliance on journal brands and impact factors benefits established journals

- and so we go back to #1.

There is so much at play here that I could talk for a full hour on just these challenges and we would still not be done. I am sure that you have touched on many of these throughout the week. At play here are fundamental questions of the value of public education, the market logic that has permeated the academy, the vertical integration efforts of companies like Elsevier, the challenges in the academic labour market, and so on.

The role of incentives

But I noticed a trend in all my time attending scholarly communication gatherings, sitting on the board of SPARC, and traveling. It seemed as though every conversation aimed at tackling these challenges came down to the same issue: incentives.

These conversations are taking place at all levels. From faculty and librarians to university provosts and all the way up to science ministries.

For example, the 2017 G7 Science Ministers’ Communiqué reads as follows: “We agree that an international approach can help the speed and coherence of this transition [towards open science], and that it should target in particular two aspects. First, the incentives for the openness of the research ecosystem: the evaluation of research careers should better recognize and reward Open Science activities.”

Another example, this time from an article by 11 provosts (2012) offering specific suggestions for campus administrators and faculty leaders on how to improve the state of academic publishing: “Ensuring that promotion and tenure review are flexible enough to recognize and reward new modes of communicating research outcomes.”

And finally, from research conducted at the University of California at Berkeley’s Center for Studies in Higher Education (2010): “there is a need for a more nuanced academic reward system that is less dependent on citation metrics, slavish adherence to marquee journals and university presses, and the growing tendency of institutions to outsource assessment of scholarship to such proxies.”

What do we know about incentives?

There is some existing research into the role of incentives in faculty publishing decisions.

For example, a three-year study by Harley and colleagues (2010) into faculty values and behaviors in scholarly communication found that “The advice given to pre-tenure scholars was quite consistent across all fields: focus on publishing in the right venues and avoid spending too much time on public engagement, committee work, writing op-ed pieces, developing websites, blogging, and other non-traditional forms of electronic dissemination.”

Related work by Björk (2004) similarly concludes that the tenure system “naturally puts academics (and in particular the younger ones) in a situation where primary publishing of their best work in relatively unknown open access journals is a very low priority.”

But most of this work—and we did a pretty comprehensive literature review—is based on surveys and interviews, mostly within a single university a single discipline, and is relatively limited in scope.

The Review, Promotion, and Tenure Project

Our approach was different. We wanted to look at what was written in the actual documents that govern the Review, Promotion, and Tenure process.

We ended up collecting 864 documents from 129 universities and 381 academic units. We chose universities by doing a stratified random sample across institution type using the Carnegie Classification of Institutions for the US, and the Maclean’s Ranking for Canada. Many of these documents were undated, but some dated as far back as 2000.

We collected documents from the academic units of 60 of the 129 universities in our sample:

- 98 (25.7%) from the Life Sciences;

- 69 (18.1%) from Physics, Science and Math;

- 187 (49.1%) from the Social Sciences and Humanities; and

- 27 (7.1%) from multidisciplinary units.

Which means we have, as far as we know, the most representative set of documents that govern the RPT process. We were then able to do text searches on these documents for terms or groups of terms of interest, such as “open access” or various language related to citation metrics.

Does anyone want to take a guess at how many mentioned Open Access?

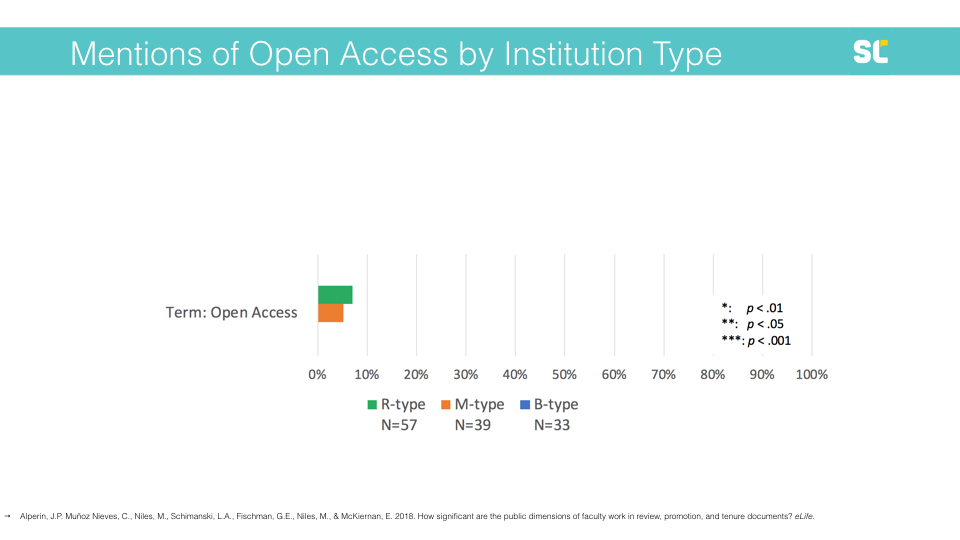

Above, you’ll see how often OA is mentioned by various kinds of academic institutions, including those focused on doctoral programs (i.e., research intensive; R-type), those that predominantly grant master’s degrees (M-type), and those that focus on undergraduate programs (i.e., baccalaureate; B-type).

What we found is that OA was mentioned by only around 5% of institutions. Just to give you a point of comparison, citation metrics, such as the journal impact factor or the h-index, were found in the documents of 75% of the R-type institutions.

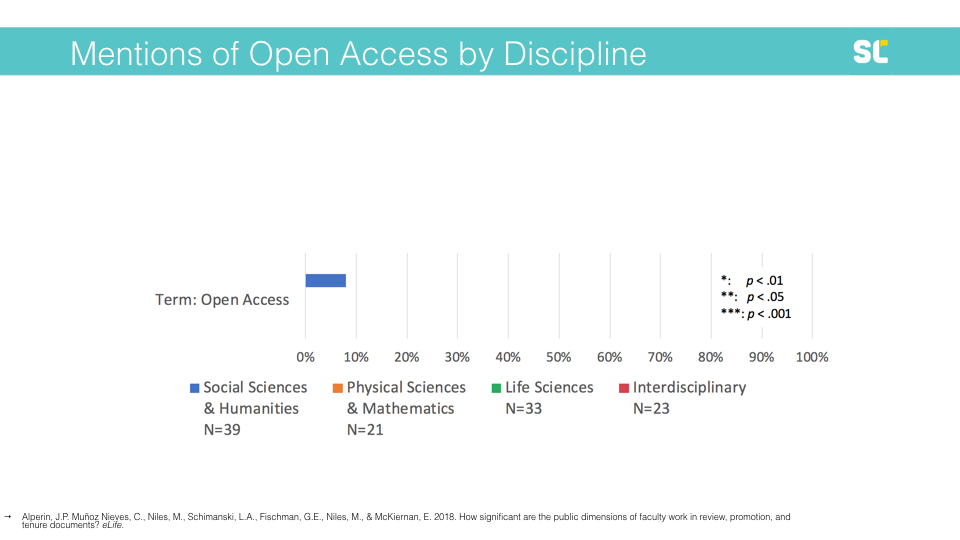

When we look by discipline, we find the mentions of OA are exclusively found in units related to the social sciences and humanities.

Digging further into open access

Now, some of you may be thinking that 5% is not so bad. If you are feeling encouraged that it is mentioned at all, you should remember that at the beginning of this talk I warned you things would get depressing before they got better.

Here are some examples of mentions of open access.

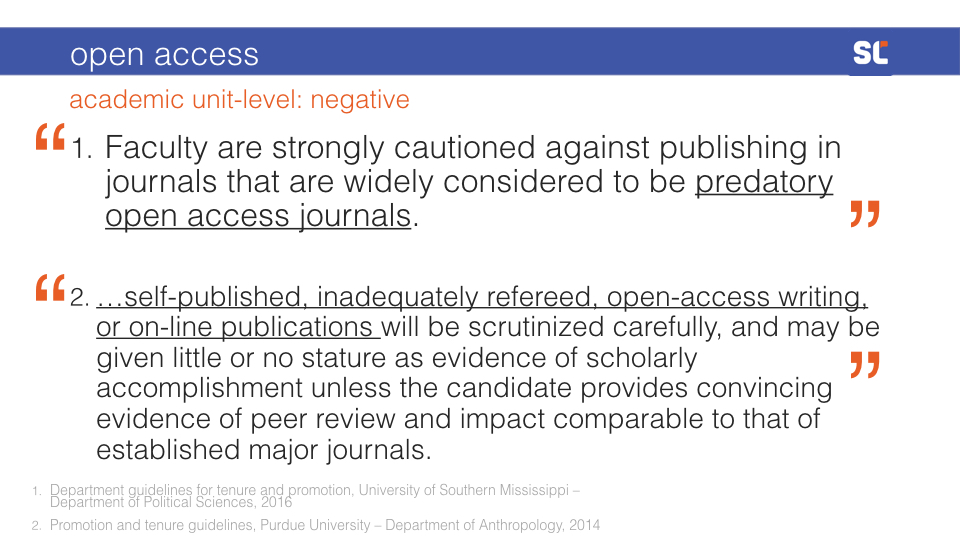

From the University of Southern Mississippi Faculty Handbook (2016): “Unfortunately, it is now possible for candidates who receive negative evaluations at lower levels (department, department chair, College Advisory Committee) to compensate [for these negative evaluations] by using online journals which feature ‘instant publishing’ of articles of questionable quality for a fee. These journals have been described as ‘predatory open-access journals.’”

Another negative example from USM, this time from the Department of Political Sciences (2016): “Faculty are strongly cautioned against publishing in journals that are widely considered to be predatory open access journals.”

And from Purdue University’s Department of Anthropology (2014): “…self-published, inadequately refereed, open-access writing, or on-line publications will be scrutinized carefully, and may be given little or no stature as evidence of scholarly accomplishment unless the candidate provides convincing evidence of peer review and impact comparable to that of established major journals.”

And finally, a more neutral mention of OA, this time from the University of Central Florida (2014): “Open-access, peer-reviewed publications are valued like all other peer-reviewed publications.”

What do the RPT documents ask for?

So, what, exactly, do the RPT guidelines ask of faculty?

Here is a sneak peek of a chapter we’re publishing in a forthcoming handbook on linguistic data management. We have not preprinted it yet, because we’re hoping to expand it a little and eventually submit it to a journal. In it, we performed a more sophisticated analysis than simply looking up single terms.

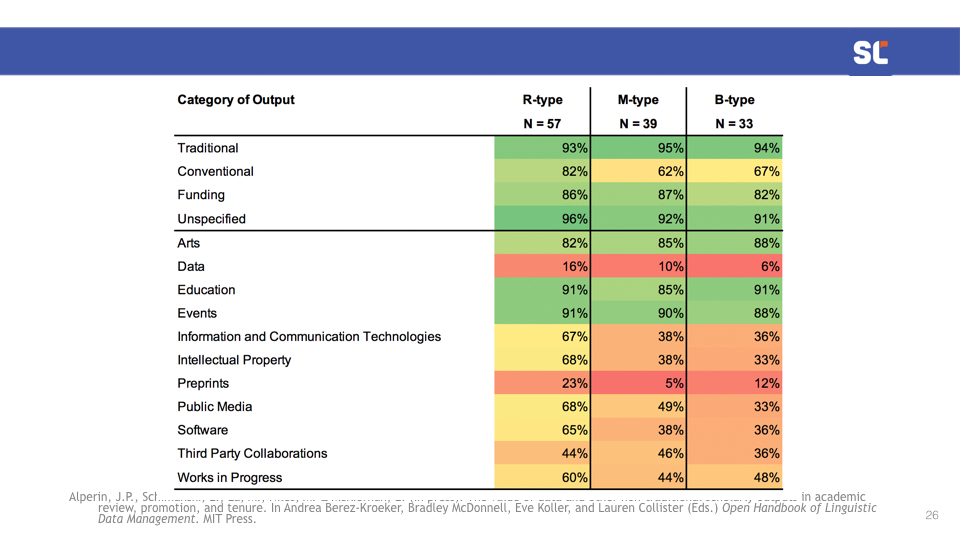

In the paper some of you may have already seen, we reported the number of mentions of the most traditional research outputs (e.g. books, journal articles, etc). In this latest work, we took a deep dive into the documents to try to identify a list of all of the outputs they mention. I won’t get into the methodology for doing this, suffice to say that identifying and classifying outputs is not an exact science. There’s lots of researcher’s interpretation at play here.

What you see at the top of this chart is that the most traditional outputs—books, journal articles, and conference presentations—are still pretty ubiquitous. We separated out these traditional outputs from other conventional outputs, like abstracts, book reviews, and editorials. As you can see, these conventional outputs are also mentioned in pretty much all the documents we analyzed.

But so are some other categories of outputs. Arts-related outputs—like exhibitions and performances—appear in most of the documents, as do education-related ones—like textbooks and syllabi. Events—and here we mean organizing things like colloquiums, conferences, or symposiums, not attending them—are also mentioned frequently.

There are a lot of other interesting things going on here—we will have the paper out soon enough so you can read more about them—but what I want to point out today is that the primary problem isn’t about acknowledging alternative forms of academic work, teaching activities, or symposiums. As you can see, there is already a recognition within the documents that scholarship and the job of faculty is quite broad.

But, we do see several problems with the way these different outputs are portrayed. As with Open Access, not every mention of an alternative form of scholarship is encouraging. We found several examples like this one:

“Promotion—scholarship will be judged, on a Department-specific basis, according to the quality of the research program, reflected in roughly descending order by the following kinds of publications: refereed books, book chapters, and articles, including major refereed research monographs; textbooks, edited books, other monographs and articles in non-refereed journals, book chapters, book reviews; other forms of scholarship, e.g., conference papers, research grants, editorship of journals, conference organization, development of computer-assisted learning, data bases, software.”

But the bigger problem—as I am coming to learn through this project—lies in how contradictory we are. Guidelines from a different unit in the same faculty (Faculty of Arts at the University of Calgary) read: “All research, scholarship and other creative activities shall be assessed on the merits of the work, regardless of the form in which they appear. Electronic publications—whether books, articles, journals, or databases—shall be considered equivalent to more traditional forms of publications if they are subjected to the same rigor of informed peer review or appropriate refereeing.”

You may have realized that this was the turning point. The uplifting ending is coming. Everyone, perk up in your chairs.

These contradictions are not just found between units, they are simply part of who we are.

These contradictions are not just found between units, they are simply part of who we are. Let’s not forget who writes these guidelines! We write them ourselves! It is sometimes very easy to forget when discussing systemic challenges in academia that, for the most part, we are collegially governed—that is, faculty themselves make up these rules. Although we are certainly subject to pressures from the outside, we create these guidelines ourselves. This makes understanding the factors that guide faculty decision making extremely important.

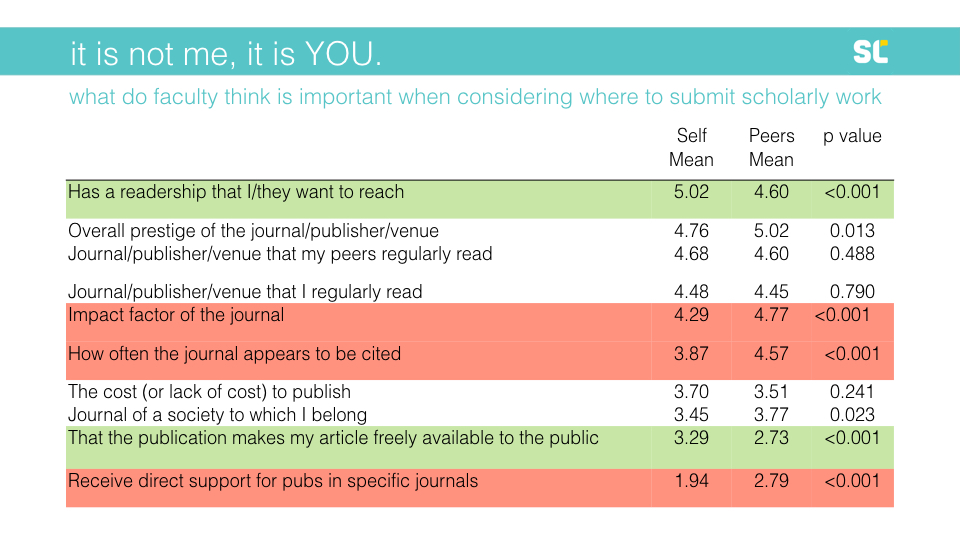

We decided we needed to do more than look at documents. So, in the second year of the project, we surveyed a few hundred faculty at the institutions for which we had academic unit-level documents. We asked them what factors affect their own decision making when they choose where to publish and—and here I should credit a conversation I had with Cameron Neylon ages ago—we also asked them what they thought their colleagues thought.

Here, if we look at the “self” column, you’ll see that journal readership is the top factor faculty say they value when deciding where to publish their work. Numbers 3 and 4, respectively, are submitting to a journal their peers read and submitting to one that they themselves regularly read.

Where it gets really interesting, however, is in the second column: what faculty think their peers value when considering where to submit. I’ve highlighted the items for which there are statistically significant differences between faculty members’ own publishing values and those they attribute to their peers. The rows in green are factors faculty say they value more than their peers; those in red are ones they say their peers value more.

What you’ll notice is that respondents value the journal’s audience and whether it makes its content freely available more than they think their peers do. On the flip side, they think their peers are more driven by citations and merit pay.

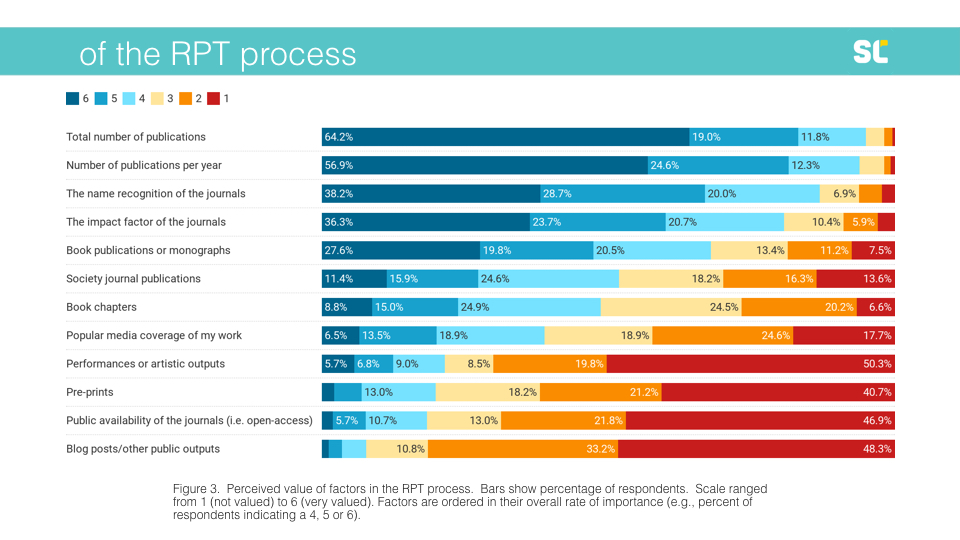

Next, we asked them about what they thought was valued in the RPT process, which is different from asking them how they make decisions on where to submit. Here, we also get a fairly cynical picture: faculty think their peers who sit on RPT committees value factors like total number of publications, publications per year, name recognition of journals, and journal impact factors (JIFs).

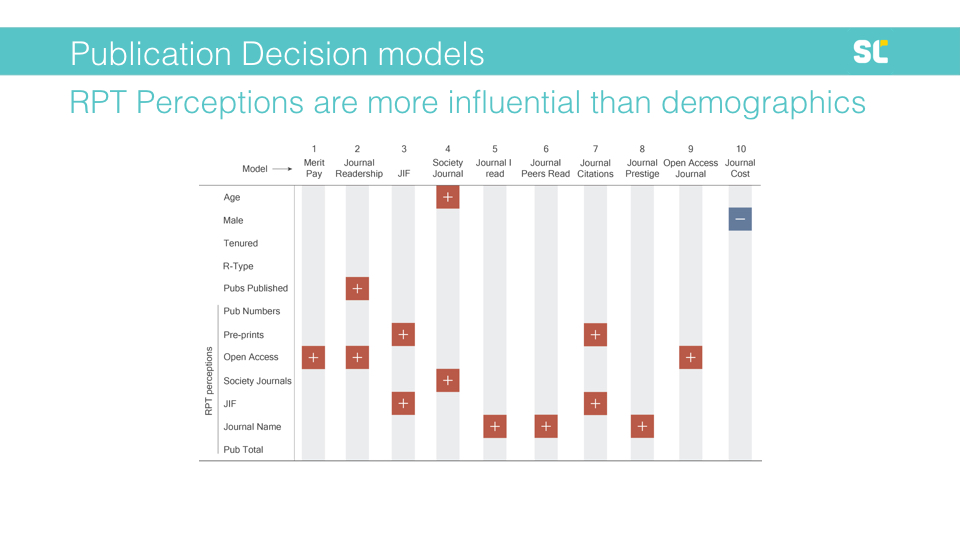

Next, we put all of this together using some statistical models. In this figure, you’ll see the factors influencing where faculty submit across the top, and the factors that might influence those factors down the first column. It paints a clear picture: faculty perceptions of the RPT process have a significant influence in many of the models—more so than demographic characteristics.

This means, if you look at model 9, for example, that a faculty member is more likely to consider whether a journal is open access if they believe that OA is valued in the RPT process. Similarly, they are more likely to care about the journal’s readership if they think that OA is valued in the RPT process.

What are we to make of all this?

Of course, it is perhaps unsurprising that faculty seem to be largely driven by readership and peer exposure to their work when deciding where to publish. But what is perhaps more surprising is the extent to which what our perceptions about what others value can shape those publications decisions, especially in terms of what we perceive is valued in the RPT process. That is, it seems that any shift away from the journal impact factor and the “slavish adherence to marquee journals” (as one paper put it) may be challenged not by faculty’s own values, but by the perception of their peer’s values, which are markedly different from their own.

One place where faculty seem to be getting these perceptions is in the RPT documents themselves. As you’ve seen, these mention traditional outputs more than anything else, highlight metrics like the journal impact factor (especially at R-Type institutions), and rarely discuss open access (and, when they do, usually only do so in a negative way).

“These guidelines are actually reflections of the tensions that exist between what we value and what we think our peers value.”

But these documents are not all negative. They do talk about publicness, education-related outputs, community-building activities, and more. And so, if we want to create change, we need to consider the role of things like RPT documents. We often treat these documents as reflections or encapsulations of what we, as faculty, value. But, I would argue that often, these guidelines are actually reflections of the tensions that exist between what we value and what we think our peers value.

This leads me to conclude that the answer to the title of this talk—“Would including open scholarship in tenure guidelines move the needle?”—is NO. Simply adding or changing these documents would not move the needle. These documents matter only in as far as faculty believe they are a reflection of their peers’ values. Faculty themselves already value finding the right venue and format for their work. They just don’t believe these factors will be valued or prioritized by others, regardless of what the documents say. I think that what is needed today are fewer arguments about the citation advantage of publishing in open access journals or about the ethical imperative of making our work public, and more conversations that will help faculty resolve this tension.

And so, instead of (or, perhaps, in addition to) campaigning to change RPT documents, I have something else for you to do. Whenever you are at your next conference reception, instead of making small talk about the great weather we are having or about what an awful travel experience you just had, I invite you begin a conversation by sharing with your colleague why access to research matters. Because it does.

Thank you.

1 Comment

Comments are closed.

[…] invite you to begin a conversation by sharing with your colleague why access to research matters. Because it does.” By sharing our values and thoughts on the RPT process, we can cultivate an academic culture […]