Keynote talk: The most innovative methods are sometimes the simplest

Keynote presented by Juan Pablo Alperin at the 13th annual EBSI-SIS Information Science Symposium on April 28, 2021.

Thank you very much for this invitation.

Before I begin, let me begin by acknowledging that I am speaking to you from the traditional unceded territories of the Coast Salish people, including the xʷməθkʷəy̓əm (Musqueam), Skwxwú7mesh (Squamish), and səl̓ilwətaɁɬ təməxʷ (Tsleil-Waututh) Nations. I am incredibly fortunate to have the opportunity to live, work, and take in the beauty of these lands on which I am an uninvited guest.

I want to continue, by way of introduction, to tell you that it is a real treat to have an opportunity to speak to this distinguished group of library and information science students. You probably don't know this, but although my work intersects with information science more than any other discipline, I work in a Publishing Studies program, which offers a Masters of Publishing degree that is oriented towards the publishing profession. This means I have very few opportunities to address graduate students who might, perhaps, I hope, be at least slightly interested in my research. The MPub students who I teach get to experience a very different side of me—one that discusses the issues I see with technologies, the Web, and how both of those things affect the content industries. While there are graduate students on my team at the ScholCommLab, it is not quite the same thrill as having a whole crowd of you to address directly.

And so, when I accepted to give this address, I decided I would use it to get out of my system the kind of advice that I would have the opportunity to give regularly if I were an Information Science Professor teaching at any of your universities.

That's why the title of my talk is: "The most innovative methods are sometimes the simplest." (I admit, that in the interest of drawing you in, I almost omitted the word “sometimes.") I could have also titled this presentation: "It is more important to ask a good research question than to have a cool research method."

But, I wanted you to come, so you got the more click-baity title.

Underneath what will be a somewhat lighthearted talk are some serious issues that plague academia—ones that I'd be happy to take questions on at the end—that I will only quickly brush upon here. Each one of these issues could be the basis for a keynote. And each one raises questions that I think about because my subject matter is academic careers and scholarly communication, but also because I faced them myself when I was a graduate student.

- For all the critiques of publish-or-perish culture, the pressures to publish keep growing.

- For all the critiques and counter-movements, the importance of accumulating citations or otherwise rising in various metrics continues to persist.

- Not unrelated to the previous points, disciplinary posturing and positioning (i.e., "staking your ground" as a scholar of a given field) continue to play a role in determining how you approach your scholarship.

- Again, not unrelated, the journals you are pressured to publish in (or, at best, nudged towards) often predetermine the questions and methods you can use.

These problematic elements of academia draw a terrain through which there are only a few easily identifiable paths to success.

Obviously, we could go into more detail about each of these issues and beyond. But I simply want to point out that these—I would say, problematic—elements of academia draw a terrain through which there are only a few easily identifiable paths to success:

- Publish a lot by applying known methods to new datasets or areas. Information science is FULL of these kinds of scholars.

- Invent, or borrow from other disciplines, new methods and use them to offer novel insights into old problems. Computer science is increasingly popular here.

- Or, if you really want to stand out quickly, invent or borrow a method, apply it to a novel question, and then crank out a whole bunch of papers quickly as you ask that question over and over again.

What I want to do with my remaining time today is walk you through how I have managed to, on multiple occasions, use extremely simple methods to shed light on questions in an innovative way. This has allowed me to not get caught up in the disciplinary struggles, nor to find myself playing the game of cranking out endless meaningless publications. I hope that some parts of this trajectory will resonate with where you are at, and hopefully serve you well as you proceed in your own academic careers.

My academic story begins when I was a doctoral student. I had been working in Latin America and had been trying to better understand Latin American scholarly publishing, which is largely all Open Access. I knew I wanted to do my dissertation on this topic. I had worked with three major regional players who, by combining their resources, provided me with access to a directory of every journal in the region, the metadata of over 1300 journals, the download data of the same journals dating back years, citation data for about half of those journals, and more. I also had the distinct advantage of having a computer science background, so I possessed the computation skills to manipulate and crunch this data, plus the mathematics knowledge to be able to understand—even if I had not yet learned—sophisticated statistical methods.

I was doing my PhD in a School of Education, and so my own background and the data I had access to gave me a competitive advantage over many of my Ed School colleagues. It became clear to me that, to “succeed” in academia, I should deepen my methodological expertise and further distinguish myself from my peers. So I set about trying to do this:

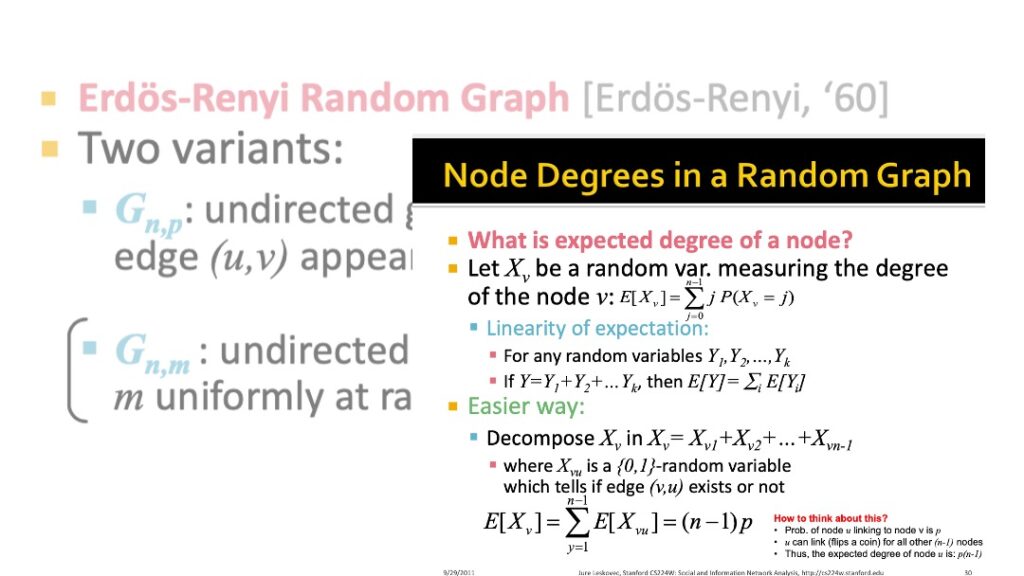

I took a class on network analysis, as well as multiple workshops, and then struggled for weeks to figure out how to run some Erdős–Rényi (Random Graph) models. This approach is the equivalent of using a "normal distribution" in statistics—you can compare your graph and see if it differs from a randomly generated one. I was going to use this to see how national, regional, and international networks behaved.

Then I took a class on Natural Language Processing, and I learned how to do topic modelling—labelled and unlabelled, supervised and unsupervised, etc. I learned a whole complicated suite of methods for figuring out what articles clustered with each other, all to see if I could figure out if Latin American scholarship was engaging more with itself than with scholarship from beyond.

My point is this: I had a unique dataset and a massively understudied problem space, so almost any question I wanted to tackle could have produced valuable insights. I struggled, until I realized that what I really wanted to know was who was using this research. I kept trying to find a clever statistical, computational, or quasi-experimental way of answering the question: "Who uses this stuff?"

Until I realized the solution: JUST ASK THEM.

OK, at this point, you might say: “But this particular solution only worked because you had access to the portals.”

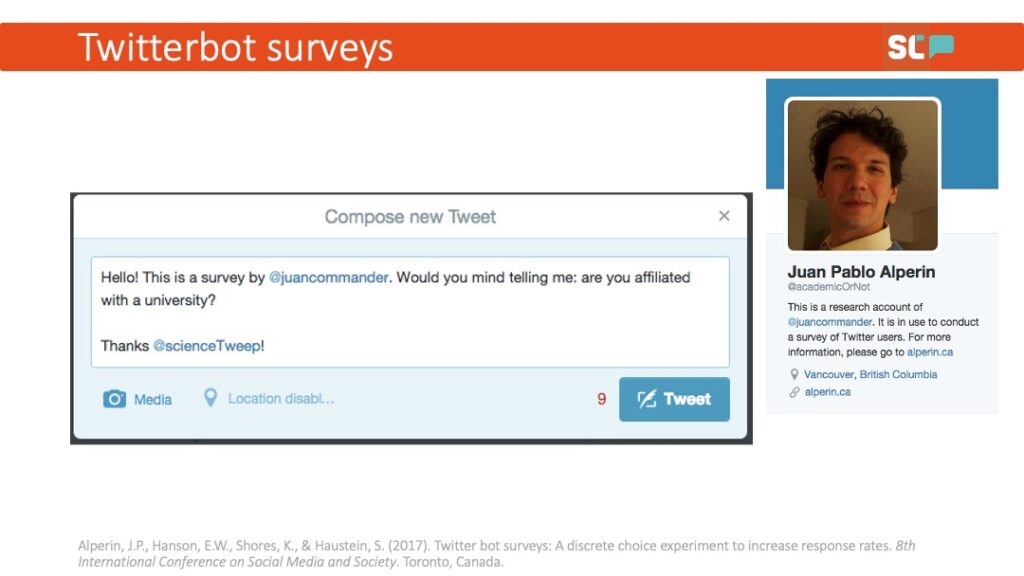

While that may be true, I came across the same problem when I was trying to make the argument that social media could allow members of the public to access research. It was the earliest days of what are now known as Altmetrics, and lots of folks had been trying to answer the question: “Can we know whether the public reads research by looking at social media?" I had just come off the high of doing this super simple pop-up survey, so I thought: How can I replicate this? Say “hello” to the creation of Twitter-Bot Surveys.

For those of you who fall more on the library side and are interested in documents and textual corpora, the same sort of approach can apply beyond social media. The conversations about the various issues I outlined earlier—those issues about the need for many publications, the rising importance of metrics, etc—all seemed to come back to the incentive structures in academia. The argument I kept hearing was that faculty wanted to do things differently, but review, tenure, and promotion (RPT) committees kept evaluating people in this way. We even saw a proposal to run an advocacy campaign to "change the form" of the RPT process—all based on no evidence.

And so, our team came up with what was, again, a pretty simple method to determine whether this argument actually reflected reality: we collected documents related to the Review, Promotion, and Tenure process. How? We just emailed people and asked them for them! Obviously, we did some planning around sample sizes, etc. But the plan was simple: collect documents and then check whether the terms of interest were present in the texts or not. Again, this method is not complicated. Instead, what is innovative here is the use of a simple method to answer an important question.

This is what I want to emphasize: although I have accidentally become one of those scholars who is known for innovative methods, I really don't think any of these are innovative at all. There are some really clever studies out there using really clever methods, but, in most of my work, I don't think the methods are innovative or sophisticated at all. Pop-up surveys already existed at the time I used them, as did twitter bots, and checking the presence of specific terms in a collection of documents is about as simple an analysis as you can imagine. What has made these papers and studies successful? Why do I—and, I think, others—consider them to be so interesting?

They ask questions that people—and not just a select few—really want to know the answers to. I really cared about the "so-what" during all of these research projects. When you do that, it frees you from the pressure to get a perfect answer. If the answer is important, having a complete answer is not essential. That is, instead of trying to answer a boring question in a clever way, it is better to answer an interesting question in a boring way.

If the answer is important, having a complete answer is not essential. That is, instead of trying to answer a boring question in a clever way, it is better to answer an interesting question in a boring way.

Ask a good question and look for a "good enough" way to approximate an answer. If your question is good enough, a perfect answer is not necessary.

I want to go back to the earliest example I gave—the one about who was reading Latin American scholarship. Did my method control for all demographics? No. Could I have tried to get multiple answers and link them together to form a more complete picture of the users of Latin American research? Yes. What about linking those answers to Erdős–Rényi models? Sure! You could do that. But, at the end of the day, the most compelling thing to come out of my PhD was the answer to a pop-up question: "I am interested in this research article for my personal use." This view was expressed by 25% of respondents.

It was incomplete, it was imperfect, but, as it turned out, it was also an innovative way to very simply answer a question that everyone in the Open Access movement cared about.

By all means, come up with clever studies, think through all the interesting angles you can, make your research as robust as possible... But my advice is to first spend time thinking about what question you really care about and why.

By all means, come up with clever studies, think through all the interesting angles you can, make your research as robust as possible. Do high quality work. This is all absolutely essential. But my advice is to first spend time thinking about what question you really care about and why. Only after you are clear on that question should you figure out how innovative your method needs to be. It might turn out that, just as with the examples I've shown you today, often the most innovative thing you can do is to answer your question as simply as possible.

Thank you.

Four recommendations for improving preprint metadata

By Mario Malički and Juan Pablo Alperin

This blog post is inspired by our four part series documenting the methodological challenges we faced during our project investigating preprint growth and uptake.

Interested in creating or improving a preprint server? As the emergent ecosystem of distributed preprint servers matures, our work has shown that a greater degree of coordination and standardization between servers is necessary for the scholarly community to fully realize the potential of this growing corpus of documents and their related metadata. In this post, we draw from our experiences working with metadata from SHARE, OSF, bioRxiv, and arXiv to provide four basic recommendations for those building or managing preprint servers.

Toward a better, brighter preprint future

Creating a more cohesive preprint ecosystem doesn’t necessarily have to be difficult. Greater coordination and standardization on some basic metadata elements can continue to allow a distributed approach that gives each community autonomy over how they manage their preprints while making it easier to integrate preprints with other scholarly services, increase preprint discoverability and dissemination, and develop a greater understanding of preprint culture through (meta-)research. We believe this standardization can be achieved through voluntary adoption of common practices, and this blog post offers what we believe would be useful first steps.

We understand that preprints servers often lack the human and material resources needed to ensure the quality and detail of every record that is uploaded to their systems. However, we believe many of the recommendations set out below can be carried out with relatively low cost by improving preprint platforms. These investments can be made collectively by various preprint communities. To help, we have included links to open-source solutions that might be used to support the work. We also invite and encourage others to share their experiences and insights so that we can update this post with additional best practices.

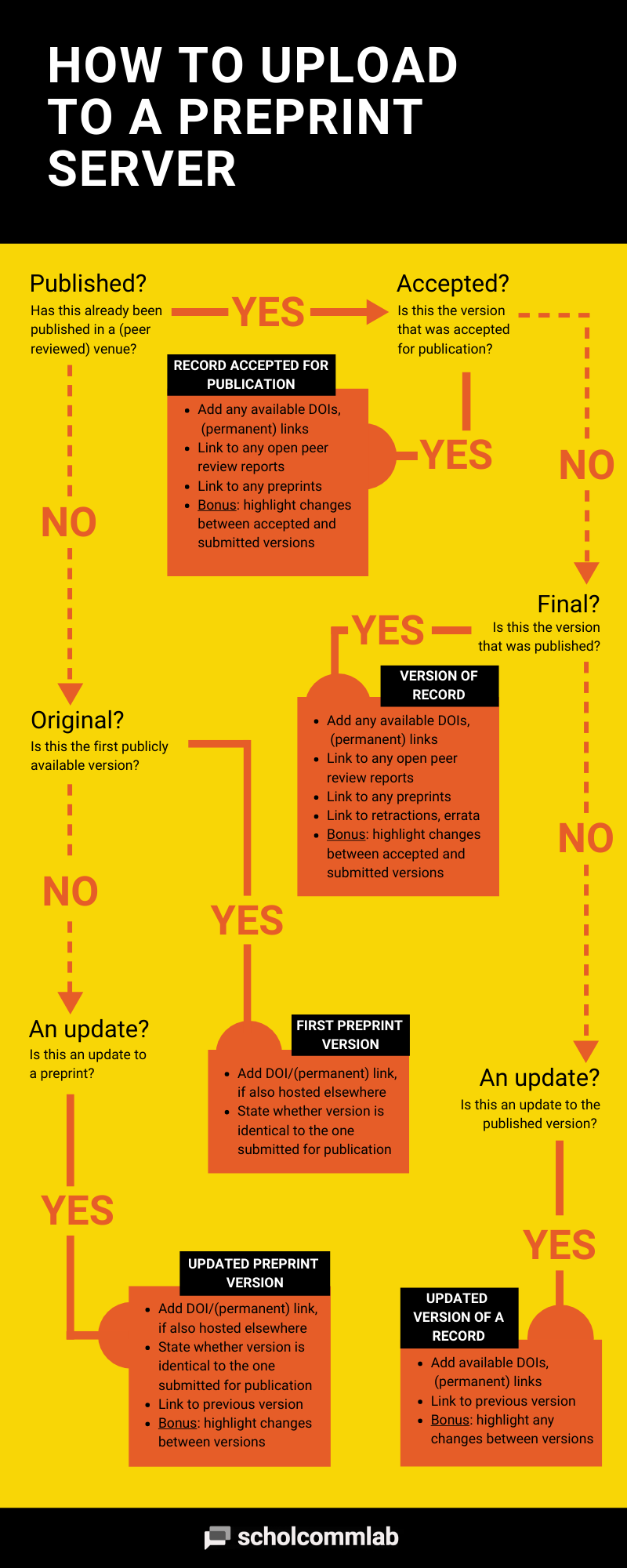

Recommendation #1: Clearly identify each record’s publication stage

Our most basic challenge when working with metadata of preprint servers was the inability to identify which records were preprints and which were published (peer reviewed) papers. While a definition of what constitutes a preprint is not universal,1 we highly recommend adopting a basic taxonomy of documents and document versions so that it becomes possible to clearly distinguish between the following types of documents:

- unpublished record (preprint): This record is usually posted for fast dissemination to the research community or for obtaining feedback. It has never been published in a peer reviewed venue (e.g., scientific journal, conference proceedings, book, etc.). In some research communities, the initially posted version or an updated version (see below) may also represent the final scientific output—that is, it will never be sent for peer review or publication in a traditional publishing venue. In Crossref, this type of record is classified as “posted content.”

- published (peer reviewed) record: This record has already been published (or accepted) in a peer reviewed publication venue. The corresponding Crossref classifications include journal articles, books, conference proceedings, and more.

We are aware that some currently existing preprint servers only accept one of these two record types, while others facilitate direct submissions of records to scientific journals, or vice versa. Nevertheless, in order to capture all aspects of scientific publishing and enable integration with existing scholarly services, we would highly recommend universally adopting this basic classification and including it in the metadata.

We also recommend that servers go a step further, providing additional information about these two types of records, so that researchers and stakeholders can better understand and follow the full lifecycle of scientific outputs. Based on our research, we recommend this more detailed taxonomy:

- unpublished record (preprint):

- first preprint version: the first version shared with the public.

- updated preprint version: an updated version of a previously posted preprint. Ideally each updated version should contain a version number and include description of what has changed from the previous version (see our third recommendation below).

- published (peer reviewed) record:

- record accepted for publication: the version of the record that has been accepted for publication (i.e., after peer review but before final typesetting and editing). In Crossref, this type of record is classified as “pending publication.”

- version of record: the version as it appears in another publication (e.g., scientific journal, conference proceedings, book, etc.)

- updated version of record: a revised or updated version of the version of record. It may include changes introduced due to post-publication comments or discovered errata.

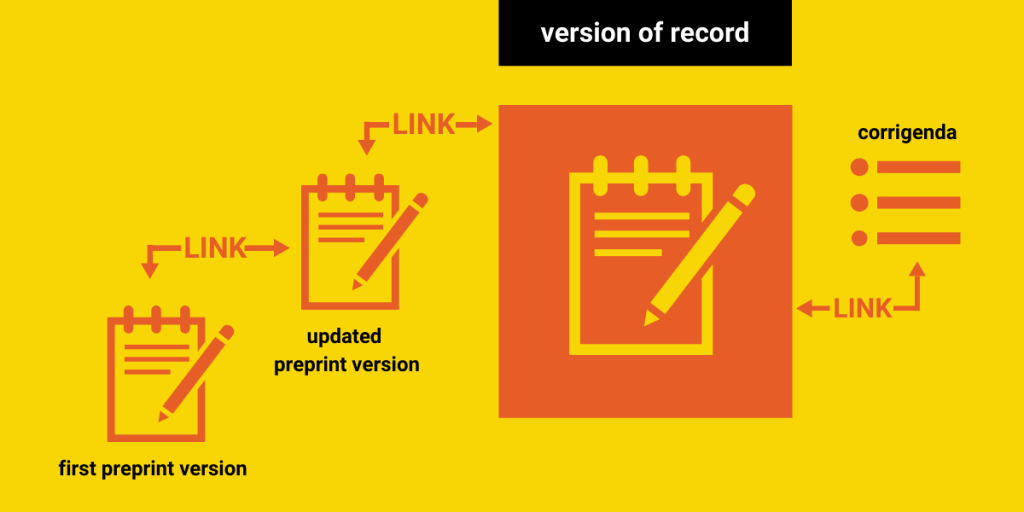

A visual breakdown of this taxonomy, along with suggestions from our following two recommendations, are incorporated in this flowchart:

Recommendation #2: Link related records

Improving understanding about the lifecycle of preprints and published records and increasing trust in their use will require that researchers and users are able to understand the relationship between preprints and other records. For this reason, we highly recommend servers make every possible effort to link the record types we mentioned above to one another, even when those versions are not stored on the same preprint server. We also recommend linking records with (open) peer review reports whenever possible.

Some servers currently link records by letting submitters enter a link, DOI, or description in a free text field to indicate connections between records. Others attempt to link records automatically. Although, in theory, these are great strategies, they don’t always measure up in practice. Our analysis found that a significant number of the links that were available on SHARE, OSF, bioRxiv, and arXiv were incorrect or incomplete There were also many instances where the free text fields had been used to enter other types of information, like comments, author affiliations, or dates.

To prevent errors like these, we recommend that preprint servers ask users to state the type of record they are linking to during the upload stage, and then confirm that the links they enter work (i.e. can be resolved). Servers could also check the Crossref/Datacite metadata (if a DOI link exists) or read the metatags on the linked page to confirm whether the document is, in fact, related. These checks could either take place during data entry or on a regular basis, using email notifications to alert authors of potential errors.

Additionally, some published versions of a record may be amended by errata or corrigenda, or be retracted. In our own research, we noticed that even preprints themselves can be retracted. All of these changes and corrections should be clearly linked to the record in question, so that stakeholders are aware of the latest status of the publication, especially if it has been found invalid in its results.

If server moderators or authors feel that records should be removed, clear reasons for doing so should be stated. We recommend servers put firm policies in place surrounding errata, corrigenda, and retractions, and consider following the Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE)’s recommendations on these issues. Any removal or retraction notices, as well as alerts related to any aspect of publication ethics, should ideally follow a standardized format. We also recommend including both a description of the actions undertaken by the server moderators, as well as a comment from the authors about those actions. More information on the issues surrounding retraction notices, as well a retraction notice template, is available at the Scientist.

Recommendation #3: Label preprint versions and describe version changes

One of praised differences between preprints and traditional publications is that preprints can be more easily revised and updated. A description of a manuscript’s evolution over time (including its movement through the publication stages described above) could offer important insights into the value of posting preprints.

However, in our own research, we were only able to determine the number of documents that had been revised on two of the four servers we studied: bioRxiv and arXiv. We are also unaware of other, more detailed studies exploring the evolution of documents throughout the publication lifecycle. For this reason, we recommend that servers capture and display the revision history of every document in their collection.

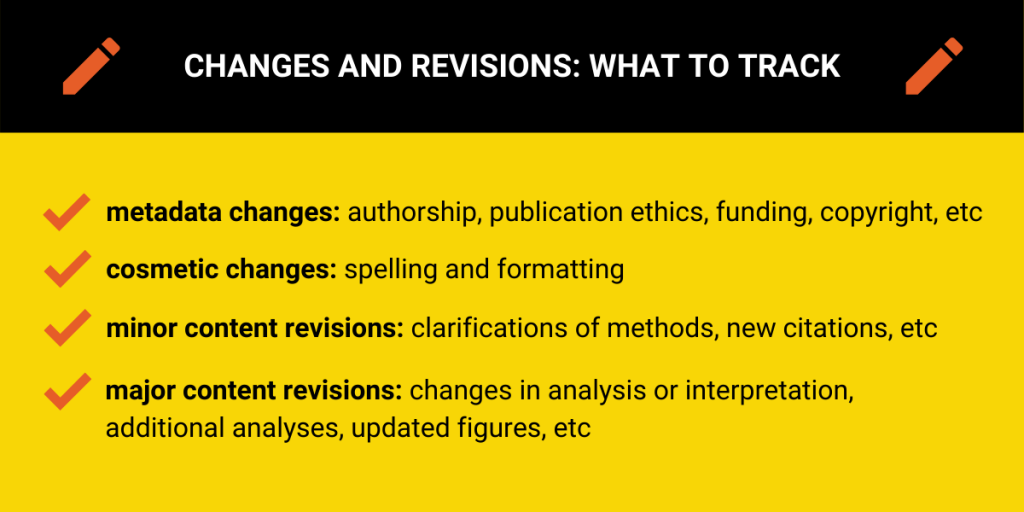

At a minimum, we recommend that all preprint servers track revision numbers and keep previous versions of documents and metadata available for review. Ideally, identifying revision history would also capture some indication of what changes occurred between versions. To this end, we suggest tracking changes along four dimensions:

- metadata changes (e.g., in authorship, publication ethics, funding, or copyright)

- cosmetic changes (e.g., spelling and formatting)

- minor content revisions (e.g., clarifications of methods, introduction of new citations, etc. )

- major content revisions (e.g., changes in the analysis or interpretations, additional analyses, updated figures, etc.)

We realize that what constitutes a major or minor revision may differ between communities, but we are less concerned about a rigorous determination of the extent of changes than we are with some general indication of what has changed. For example, in our research we often saw small stylistic corrections posted only minutes after the posting of a preprint. These kinds of changes are quite different from the major revisions to an analysis that might be made after receiving community feedback—and we recommend that the revision history reflect this difference.

Servers should also make it clear to authors during the submission process whether small or cosmetic changes can be made to uploaded documents, or whether making any changes will require the creation of a new version (and associated metadata). Servers could also consider providing additional details on exact differences between versions (e.g., the number of words, figures, tables, outcomes, references, etc.) by use of automation or by providing a free text field for users to describe the differences in their own words. For those depositing preprint metadata to Crossref, we recommend that DOIs between versions be linked according to Crossref’s recommended practices (i.e., by using the intra_work_relationship tag with the “is Version Of” type).

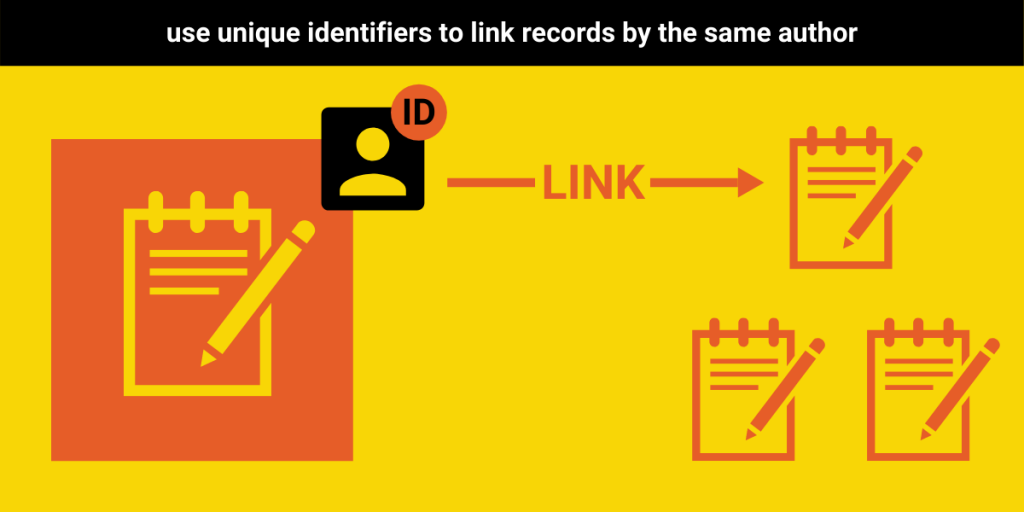

Recommendation #4: Assign unique author identifiers and collect affiliation information

Just as tracking the number of preprints is fundamental to understanding preprint uptake, so is knowing the number of individuals who are participating in the practice. Universally adopting author identifiers, both within and between preprint servers, would greatly facilitate future research in this area analysis. That said, we understand that there are communities who disagree with such centralized tracking of individual outputs. As such, we recommend that those who are comfortable with the use of global identifiers do so, and that those who are not focus on improving their handling of author names and identities.

To this end, we recommend that, at the very least, servers assign an internal identifier to each author and co-author. Alternatively, they could collect or include identifiers from existing systems (e.g., ORCID iD, Scopus or Researcher iD, Google Scholar iD, etc.). The goal here should be to reduce the difficulties in disambiguating author names so that it is possible to know when two records are authored by the same individual. Otherwise, small differences in spelling, the use of non-English marks (i.e. diacritical marks), or other tiny discrepancies can make doing so almost impossible.

We would also highly recommend that providers allow users to include information about shared or equal authorship or corresponding authorship when uploading a record, as these data are widely used in bibliometric analysis and are relatively easy to collect.

In addition to helping standardize author names and including an identifier for disambiguation, preprint servers would benefit from collecting affiliation information for each author. Ideally, each affiliation should also have an accompanying identifier, making use of established systems like Ringgold Identifier (proprietary) or the emerging Research Organization Registry (open). If using an identifier isn’t possible, we recommend collecting country and institutional affiliation as individual fields, with auto-complete features to help standardize names between preprint servers.

Final considerations

These four recommendations represent our main suggestions for improving the state of the preprint ecosystem. We believe that implementing these recommendations would increase trust in and discoverability of preprints, and would allow researchers to undertake the same (meta)studies that have so far mostly been done on published journal articles or conference proceedings.

This list of recommendations is by no means exhaustive. In our next post, we will provide additional recommendations that preprint moderators could consider. We also welcome feedback and additional suggestions for best practices that we can add to the list. As the scholarly landscape evolves, preprint servers need to evolve with it. We hope these recommendations help make that evolution possible.

To find out more about the Preprints Uptake and Use project, check out our other blog posts or visit the project webpage.

Statement of Interest: JPA is the Associate Director of the Public Knowledge Project who is currently developing an open source preprint server software in collaboration with SciELO.

Keynote Talk: Open Education 2019

Keynote presented by Juan Pablo Alperin for Open Education 2019: Transforming Teaching & Learning at SFU on May 27, 2019.

Overview

- Introduction

- Public purpose of higher education

- Why do I practice Open Pedagogy?

- Student feedback on Open Pedagogy

Introduction

I want to begin by acknowledging that I am not an expert on Open Pedagogy, nor, as I will show you, am I the greatest educator. Although I have a PhD in Education, my doctoral work was about scholarly communications and open access, and most of what I’ve learned about higher education has taken place in the classroom, not through extensive research. There are many others—very likely including many of you in this room—who know more about Open Pedagogy, its history, and related practices, and, importantly, have experience in its successful implementation.

So, now that I have confessed this, you might wonder why I was invited to speak today, and you would be right to ask why I accepted. While I cannot speak to the former—I am still surprised when I get invitations to speak anywhere—I can certainly tell you about the latter. I have a deep commitment to making knowledge public and to open pedagogy. I see these two things as connected—each is a means of achieving the other—and I am convinced that we all benefit from there being more open pedagogy practices in the classroom. Starting, of course, with the students themselves, both by learning content knowledge and gaining an appreciation for public knowledge.

I have experimented with various open practices in my own classrooms, and I have had both successes and failures. I imagine that most of you here today share my commitment, and so I would like to use my time to share my experiences. For those who know better than me about these things, and for whom none of these pedagogical practices will be new, perhaps you can benefit from hearing the obstacles that well-meaning faculty like myself face. As we promote these practices, it is important to think about the challenges and costs of implementing them. For others who have been curious about open education, but have not had a chance to experiment with it yourselves, perhaps my experience will give you some ideas on where to start.

So this is my plan for the time I have with you today. I will begin by outlining a little bit of my thinking about the purpose of higher education. This is informed by my time in the classroom with David Labaree, a historical sociologist of education at Stanford. Then, I will share with you some of the ways in which I have experimented with open pedagogy in my own classrooms, and finally, I will read to you some of the feedback I have received from my students. This last part—if you’ll forgive me for a bit of a spoiler—will hopefully give you an appreciation for some of the challenges faced by faculty, like myself, who want to try to do things differently.

Public purpose of higher education

In talking about the public purpose of higher education, I need to acknowledge and thank Luke Terra, who was a fellow PhD student at Stanford and is currently the Director of Community Engaged Learning at the Haas Center for Public Service. Like me, Luke was also a student of Labaree, but he clearly learned the lessons much better than I. When he clearly summarized Labaree’s arguments as a guest lecturer in my class last fall, I knew I needed to strive for the same simplicity in explaining it next time. So here I go.

But, before I give you my attempt to crib from Terra and Labaree, let me ask you, as I asked the students who took my course on Making Knowledge Public: “Why do we publicly fund higher education?”

In Canada, certainly, but pretty much everywhere, some degree of public funds go towards subsidizing higher education. We give universities money for students, we give universities tax-exempt status, we fund research at universities, etc. But why? We have obviously determined that subsidizing higher education with public funds benefits society, but how? What’s the argument?

Labaree’s framework categorizes these kinds of rationales into three competing purposes: Democratic Equality, Social Efficiency, and Social Mobility.

Democratic Equality

From the perspective of democratic equality, schools are intended to develop an informed and capable citizenry. Naturally, this comes in the form of the knowledge and critical thinking skills needed to make decisions, but also the social disposition to work collectively. Luke used the example of a parent coming in to a parent-teacher conference who asks not just about how their child is doing in each subject, but also about how well they are getting along with others, whether they seem happy at school, and whether they behave well.

Schools, all the way from Kindergarten up through graduate school, play an important role in the socialization of individuals. Under this category, we have the arguments that schools give people a shared sense of purpose and equal opportunity to make decisions and participate in society.

Social Efficiency

The next perspective is that of social efficiency. From this perspective, the purpose of schools is not to prepare individuals to be able to engage in democratic actions, but rather to fulfil efficient economic roles. In this group, we would place the arguments that schooling should be equipping individuals to fulfill the economic functions (jobs) that are needed in a society. That is, that public funds should be allocated to schools to train individuals to carry out the jobs that are in demand in a market. Here you will find those who are calling for the slashing of Arts and Humanities, and probably most of the social sciences, as their economic function is less clear (maybe economists are excluded from this). As Luke put it when he came to class, where Democratic Efficiency comes from the perspective of the citizen, Social Efficiency comes from the perspective of the taxpayer.

"Where Democratic Efficiency comes from the perspective of the citizen, Social Efficiency comes from the perspective of the taxpayer."

Social Mobility

Then comes my most loathed perspective, and probably the one that is most commonly found today. The perspective that schools are supposed to serve the individual by allowing them to personally gain a better position in society, or in many cases, maintain the advantageous position that they already have. This perspective leads to a form of credentialism, where school is seen as a place to acquire the highest value credential that students can use to gain social advantage. Education becomes valuable, not for the development of human capital—the knowledge the student walks away with—but for its exchange value. This brings a market logic to universities, which views students as consumers of education. This approach lends itself to universities competing for students and striving to rise in rankings, which are viewed as a market signal of the value of a degree. Here I could go on a long tangent about the neoliberal university and how these effects are felt in so many other aspects of faculty work and in the student experience, which is why my students often leave the comment “Very enthusiastic, but rambles at times.”

But I digress.

To get me back on topic, let me say that these perspectives are not completely at odds with one another. An individual seeking social mobility may be focused on attaining a particularly high paying job, and wants the education they receive to give them access to that job, both by providing knowledge and credentials. This is a sign that the Social Efficiency perspective is also dominated by a market logic—but I am going off on a tangent again. What I really want to draw your attention to is that the rationale for why we have education in the first place matters. It affects not just what we teach, but also how we teach it. And, as I will come to describe, it also affects how students perceive their educational experience.

"The rationale for why we have education in the first place matters. It affects not just what we teach, but also how we teach it."

In this sense, it is important to highlight the main differentiating factor between the Democratic Equality and Social Efficiency perspectives and that of Social Mobility. While the former two see education as a public good—with the costs and benefits shared by society as a whole—the social mobility perspective sees the benefits of education accruing for the individual, and undermining arguments for the need for public funds at all.

As Kathleen Fitzpatrick notes in her recent book Generous Thinking: “to restore public support for our institutions and our fields, we must find ways to communicate and to make clear the public goals that our fields have, and the public good that our institutions serve.”

And this is where I stop pretending to be an education scholar—thank you Luke and David—and I begin to tell you about why I do what I do in my classrooms.

Why do I practice Open Pedagogy?

I am unequivocally in the first camp. I wish to impart to students a sense that they can—and have an obligation to—engage with the world through their intellectual pursuits. I want to empower students to be publicly engaged citizens after they leave the university. At the same time, in my research, I study the public’s use of scholarly research and actively advocate for greater access to research outputs. I do this under the belief that, when research is made freely available (as so much of today’s work is), it has the potential to make meaningful and direct contributions to society.

All of this is work is motivated, in part, by a desire to build a case for public support of education. I pursue this goal first through what I can do in my daily interactions with students, like Robin DeRosa (who many of you may know and who has been an inspiration in this area). And second, by advocating for changes within academia more broadly, as Kathleen Fitzpatrick argues in Generous Thinking.

I had been doing the work around faculty since before becoming a scholar, through the work I did with the Public Knowledge Project and the promotion of Open Access. But it was not until I arrived at SFU that I began to work on making my own classrooms more open and democratic. Now, let me actually get to talking about my own efforts. (I should say, I have been trying to do this since my very first semester at SFU. When I think back on the hubris I exhibited, as a new professor who was himself still a graduate student, I can’t even…)

Let me try to group these efforts into two categories: first, those that promote public knowledge, and, second, those that aim to make the classroom a more democratic space.

Promoting Public Knowledge

- I assign only open access readings. This might be easier for me to do than others, but I sincerely believe that it is possible to find readings that are publicly available in any discipline.

- I do this in part to show that OA is valuable (I point it out to my students);

- I pick readings that are not only peer reviewed and academic, to show that we can learn from what is written in the popular press.

- I have students post all their assignments publicly. Obviously this works better if students are primarily writing for their assignments, but my goals here are multiple:

- It gets them to think about where their content should go. I’ve given options to post on their own blogs, a site I used to help with called The Winnower, or on a blog I set up for them (they seem to like it when I give them a space);

- I’ve seen interesting things happen: assignments posted on Tumblr, posts getting shared dozens of times on social media (Instapoetry), a professor in Australia giving a negative review.

- I get students to give each other feedback openly. I do this in two ways. One is by having them actually write a comment on their post, the way any other commenter would. The other is by using online annotations, which I’ll discuss in more detail in a moment. This practice serves multiple purposes:

- they read a bit more of each other’s work;

- they practice critique when they are themselves exposed, and when they have to look that person in the eye next time they come to class (good modeling for when they comment publicly someday);

- they become accustomed to their ideas being critiqued.

- I ask students to do a public scholarship assignment. This practice is a lesson I learned from my supervisor, John Willinsky. It can involve either:

- Leaving a comment on a news story, including bringing in some additional resources;

- Editing or creating a Wikipedia page. I’ve done this without my guidance before, but last semester I tried the Wikipedia Education modules, which seem great, but which my students bailed on, because,overall, Wikipedia is actually a lot of work.

Creating Democratic Classrooms

- I have students lead seminars on topics of their choosing.

- They can come to me for advice, but, ultimately, they pick the readings;

- I try to encourage them to pick the activities, and then they guide the discussion;

- This make the class theirs, especially when paired with creating their own syllabus.

- On my first term I began to experiment with having students create their own syllabus, either completely from scratch or by working off of one of mine. This:

- Leaves room for them to work out what should be on the syllabus;

- Gives them a sense that the course is theirs—that they chose the topics, and that they are there to learn what they want to learn.

- I let students choose the percentage that each assignment is worth. In this case, I offer a percentage range for each assignment, including 0, to let students focus their attention and energy on the things they want to work on, or the things they were good at, depending on their attitude.

- I use contract grading. This involves laying out a list of things that need to be done for each grade, with every assignment graded on a Satisfactory/Unsatisfactory basis. This gives students the ability to manage their workload, dedicating more or less energy to my class if they want to.

- I offer negotiated grading. To take the emphasis off of the importance of grades, I tell students that they’ll have a say into what score they receive so that they don’t feel they are just being judged by others.

- I use open-ended assignments, with students setting their own questions and assignment length, and no specific rubrics. My goal here is to have students work to the best of their ability and to the extent of their interest.

- Finally, my favourite, is social annotation, which Esteban Morales will talk to you more about later today. (He’s in the audience now, getting nervous about whether he will have to completely change his presentation after I say all the things he planned on saying…) You’re going to get more detail, so I won’t dwell on it, but I do want to say that having students leave comments for each other and reply to each other in the margins of all the readings, does a lot for:

- Building community;

- Showing students how others think;

- Making it obvious that they are learning from each other;

- And, most importantly, getting them to think about what ideas others care about and how they can serve the community by sharing the most useful knowledge possible.

I should say, many of these practices I have learned from the HASTAC community, which I recently learned is pronounced Haystack. There are some great blog posts on there which are very much worth reading.

Student feedback on Open Pedagogy

There are resources to help educators navigate these practices, as well as guides on how to be more successful than I was, but few point to the likelihood that it won’t go very well the first few times. Nor do they answer many of the practical questions, such as: Are any of these practices actually “allowed”? Is it okay to ask your students to work in the open? Is giving them the opportunity to use a pseudonym enough? Can I ask them to post on the Web? Do I have to give them a space on a university server? What if a student does not want to post publicly, for legitimate reasons? Who is one to ask these questions to? And, most importantly, what if I ask and I get told I am not allowed to do this? Better not to ask.

So, to any of you who think that this approach to open pedagogy sounds amazing, the truth is that it is very hard to run a classroom in this way. I was super enthusiastic about doing it, but failed pretty hard on some aspects.

When I started, I certainly had not gained any appreciation of how complicated open practices can all be. I didn’t realize how much I have learned about how to practice it until recently. Even the use of what I consider to be a simple tool—Hypothes.is—proved to be complicated when I encouraged its adoption in other classrooms. I spent a bunch of time last year trying to convince instructors to adopt open annotations, and I managed to convince several others to do so. But, it turns out, I have learned something from using Hypothes.is multiple times a year for five years, and I didn’t realize the effect my approach to implementing it had on its successful implementation.

Let me share some of the less-than-amazing course evaluations I’ve received. Some are from my early terms, but some are from last semester. Here is my version of “celebrity reads mean tweets”:

- “Juan is an engaging instructor and knows the subject matter very well. I am sympathetic with the fact that many students weren't open to having their views challenged. But I think the course could have been structured in such a way that things felt less combative—a more typical seminar format would probably have helped.”

- “Overall, it seemed like Juan was trying to make the class more open, interactive and flexible—but this didn't happen. It was far too academic. I found Hypothes.is useful—but didn't have any more comments to add in class.”

- “Juan generally operates under a principle of maximum freedom, minimum clarity.”

- “The professor set up things in a purposeful way, but was not very good at explaining that purpose.”

- “Expectations were often unclear.”

When I was evaluated after 1.5 years on the job, here is what my (generally extremely positive) letter said:

Juan’s Course and Instructor Evaluation scores were quite varied in his first three terms … The cause for the variability in these scores is not easily pinpointed, but some variation might be expected in the first two teaching terms of his career, especially given his heavy teaching and service load (see below) and his very active research profile.

It is apparent that his energy and enthusiasm for teaching and for his students works well for him; he is responsive and interested to try out new things in the classroom. On arrival he immediately set about re-designing two courses and substantially updating a third. In 2015, Juan introduced the Hypothes.is annotation tool into both undergrad and graduate courses, with considerable success; we look forward to a publication that reports on this experience.

The committee unanimously recommends…with a note that some aspects of his file suggest even greater recognition. That said, the committee further noted that future successful reviews would be contingent on better teaching evaluations.

Here are some examples of criticism that I take as complementary, but that was still associated with low ratings:

- “I feel like this project was very self-taught and that could be improved.”

- “The instructor covered the content by leaving us to work it out mostly ourselves, but I believe that was the point!”

- “How successful was the instructor in communicating course content?: ‘not too successful. He did not deliver the course lectures... we did!’”

But one of my favourite student evaluations comes from when I had the pleasure of teaching the President’s Dream Colloquium on Making Knowledge Public. A class where every week we had the opportunity to discuss the various forms and merits of public knowledge. Here’s what the student had to say:

You really challenged my thinking about the responsibility to contribute rather than just consume in the public debate. I have a tendency to err on the side of keeping quiet with my opinions in a lot of contexts (except maybe in class), mainly because I have a hard time saying (or implying) that someone else is wrong. This class made me reevaluate my role and consider the perspective that it is actually also a responsibility of people with education and expertise to share that rather than hoarding it for themselves.

It's hard to balance to be generous with one's knowledge and experience without crossing the line into arrogance, snobbery and judgementalism, but this class made me rethink what educational privilege is, and how now participating in public debate and dialogue is just as much a symptom of elitist snobbery as the opposite pole of being too vocal and critical.

Like this, there are other, sometimes less explicit, but equally rewarding messages.

Open education is one piece of a very complex puzzle, but I think it can be a starting point for giving students a sense that their knowledge is a public good, and that we are all better off when they share it. If we can foster in our own classrooms this notion that education is a public good whose benefits should be accrued by society, not just by the individual, then I think we can walk back the prevailing notion that education is a commodity to be traded. We can, instead, create spaces where thinking, exploring, and sharing knowledge will thrive. I am convinced that by doing so we will serve our students and our society well.

Perhaps this is a lofty goal for this mediocre instructor, but it is one that I deeply believe is important and achievable. I look forward to learning from you all how we might achieve it together.

Thank you.

For more, check out the video of the full keynote below.

Policies and Incentives for Open Scholarly Communication

Keynote presented by Juan Pablo Alperin at the first United Nations Open Science Conference on November 19, 2019, organized by the UN Dag Hammarskjöld Library and the Scholarly Publishing and Academic Resources Coalition (SPARC).

Good morning. It is a true honour to be here and have an opportunity to share with you my thoughts on policies and incentives for open science.

I will do so in 3 parts:

Part 1: My mini-crisis as I prepared this talk

I obviously started by leafing through the Sustainable Development Goals… and then I started to feel that there are more pressing issues in the world than ensuring that research is shared openly. What could I say about incentivizing people to share their research openly that would be more important than asking them to take direct action towards ending poverty, tackling the climate crisis, ensuring healthy lives, making cities safe, and so on.

Asking myself this question was no small thing—I have spent the greater part of the last ten years doing a lot of work to promote open access to research! So I was up late one night thinking about what I could come here to say and I went to bed questioning my life choices. Needless to say, it was not a good sleep.

By the time I got back to working on this the next evening—I do all my best work after I put my son to bed—I had talked myself down from this brief existential crisis. I started by remembering how it is I got here: In case you didn’t know, nobody grows up dreaming of being a scholarly communications researcher. I fell into this line of work, just as everyone does, through a series of experiences that are meaningful for me. After growing up in Argentina and emigrating to Canada, I started sharing my university library passwords with my Tia Marta and my Tio Horacio. They were university professors in Argentina, but, as an undergrad, I had more access than they did. Many years later, I happened upon a job with the Public Knowledge Project, which I accepted largely because it would give me a chance to travel around the Latin America I had left behind, and, in doing so, speak to journal editors and scholars from around the region. It was then that I came to discover that my skills, experience, and perspectives were appreciated, and that this was a field where I could feel that I was doing meaningful work for a part of the world I felt connected to, but had largely left behind.

"To me, the connection between open scholarship and the Sustainable Development Goals is evident, if still somewhat nebulous."

But what really got me out of my mini-crisis is that I remembered that I actually believe that open scholarship has the potential to affect all of these larger societal challenges. That is, to me, the connection between open scholarship and the Sustainable Development Goals is evident, if still somewhat nebulous. I was able to talk myself down from this existential crisis by thinking through how open scholarship practices could play a role in reinvigorating the public mission of universities and helping them become vehicles for social development along all those dimensions outlined in the SDGs. I am driven by a desire to shape open scholarship with this vision in mind, and I practice open scholarship because I fundamentally believe it to be true—not because of some incentive or policy that rewards me when I do. In addition—and this is important for the topic at hand today—I practice open scholarship despite the barriers that stand in the way of doing so.

You’ll notice that I am not saying I found motivation in terms of how open scholarship affects my own career. What I just shared with you is my story, and that story is the only incentive I need.

Part 2: What open access can teach us

As I have been researching incentives for review, promotion, and tenure in academia, I have come to believe that career incentives are far less consequential than many people make them out to be. We collected hundreds of the guidelines and documents that govern the review process in universities in the US and Canada, and I have now seen work by others that looked at Europe and Asia. All of us found the same thing: that “traditional” research outputs—things like academic articles and books—are mentioned in the vast majority of the documents. Emerging forms of scholarship—it won’t surprise you to learn—are not. Open access? Virtually non-existent. Present in the documents of only 5% of institutions, and mostly in negative terms.

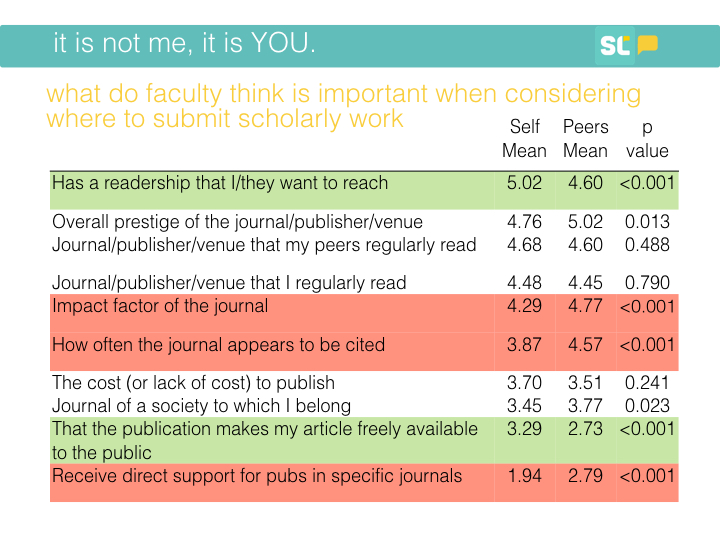

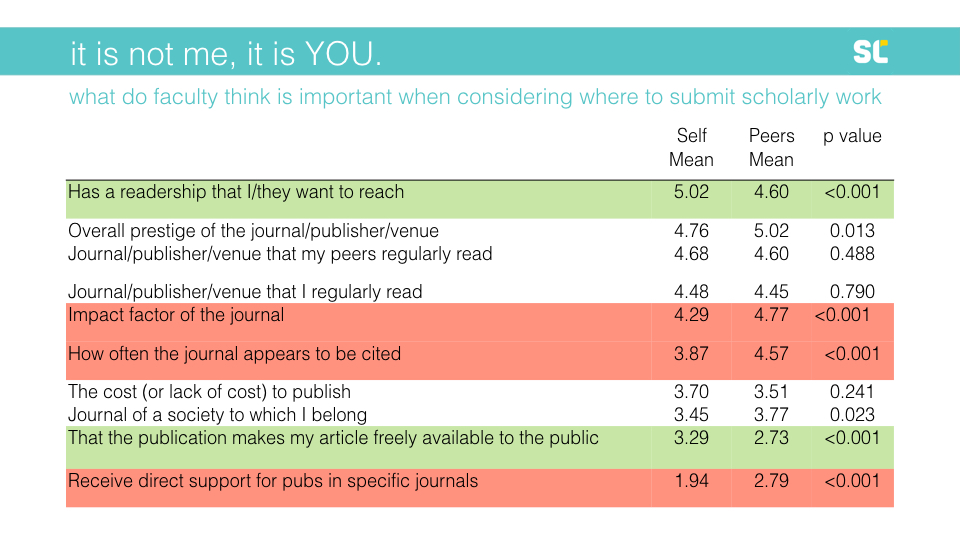

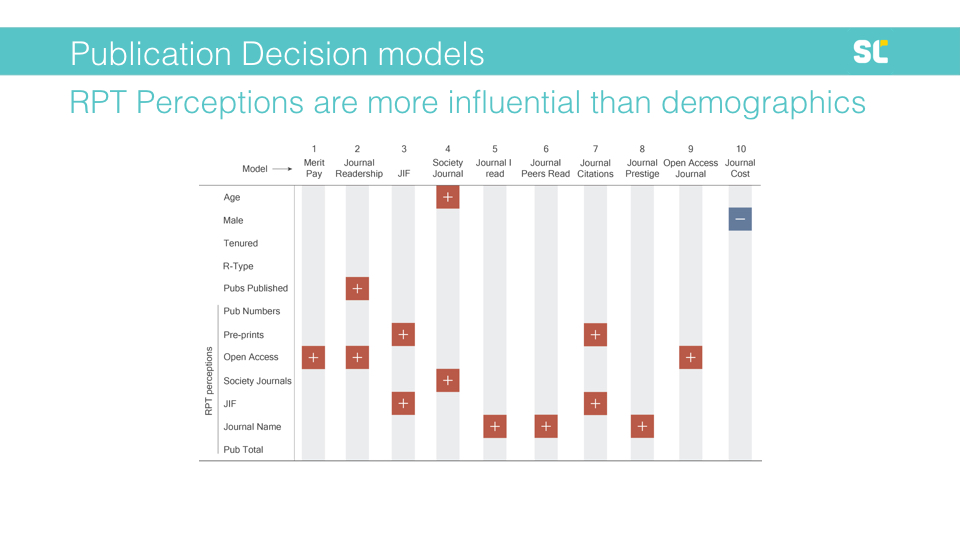

Then, when we surveyed faculty about how they choose where to publish, we found that researchers are motivated first and foremost by a desire to have their work read and to find audiences for their research. But, in survey after survey carried out around the world, when researchers are asked what they consider when choosing where to submit their work, open access comes in pretty far down the list. In some surveys, it comes in last.

"The open access incentives we put in place really only nudge scholars to go a little out of their way...in fact, the biggest thing we have done is made open access more of a norm"

And yet. And yet… we have made much progress in terms of making a significant portion of the research—currently around 50% of what is published—freely available. More importantly, a recent estimate by the team at the non-profit Our Research calculated that, if we keep progressing at the current rate, in 5 years, over 70% of what people seek to read will be open access. This is huge progress. But we have achieved this without fundamentally challenging how individual researchers do their day-to-day work. We haven’t redefined the profession, and we haven’t really changed what motivates researchers. The open access incentives we put in place really only nudge scholars to go a little out of their way—mostly to deposit articles into repositories—and, even then, they’ve had quite variable success. But, in fact, the biggest thing we have done is made open access more of a norm, and ensured that we have mechanisms in place to pay extra for those works to be available.

The lesson

So here is what I want us to consider as we think about open scholarship policies: The fact that we have largely adopted open access without fundamentally changing researchers’ motivations represents a missed opportunity.

I believe we have neglected to tackle some of the fundamental ways in which scholarship today runs in opposition to larger goals we might have as a society, including the SDGs. Or, perhaps less cynically, we have missed the opportunity to better align scholarly activities with these larger goals. Or, even less cynically still, our path for adoption of OA successfully focused on individual targets—that is, on the number of articles that are freely available—but has done less well at considering a more integrated approach that considers the many interconnections and cross-cutting ways in which open access address larger goals.

"We have neglected to tackle some of the fundamental ways in which scholarship today runs in opposition to larger goals we might have as a society, including the SDGs. Or, perhaps less cynically, we have missed the opportunity to better align scholarly activities with these larger goals."

I’m not alone in this critique of the OA movement, but I think it is particularly relevant as we push for open scholarship more broadly. Samuel Moore, a lecturer in Digital Media and Communication at King’s College London, recently wrote a wonderful article in which he describes the pre-history of the OA movement, going back to the years before the OA movement was officially born with the Budapest Open Access Initiative Declaration. In it, he points out that: “The BOAI declaration instilled the idea that OA research can be achieved without the dominant cultures of market-based publishing needing to change.”

Moore is careful, as am I, not to blame the BOIA declaration for the models of OA that ensued. But he argues quite convincingly that the text of this foundational document is indicative—not causal—of a lack of consensus around what OA should or could achieve. He explicitly points out the “techno-solutionist tone to the declaration.” Again, without wanting to minimize the value of declaration, I think it serves as a good reference point to compare what it is that we are trying to accomplish here today, and what governments and institutions around the world are setting in motion as we push for policies that promote “Open Science.”

I repeat these points that others have made because I want to argue that we are at a similar moment now with regards to open scholarship—here I very actively resist the tendency of calling it open science, a term that is problematic in its exclusion of the humanities and of other communities who are also involved in knowledge production in various ways. If we focus on personal incentives to achieve individual openness goals like depositing data, transparency, and reproducibility, we may succeed, as with have done with OA, on meeting specific targets. But we will fail to ensure that the broader goals we hope the openness will achieve.

"If we focus on personal incentives to achieve individual openness goals like depositing data, transparency, and reproducibility, we may succeed, as with have done with OA, on meeting specific targets. But we will fail to ensure that the broader goals we hope the openness will achieve."

To better illustrate what I see as the failure of open access today, I need only point to the dominance of article process charges as the dominant model for providing access. The APC model sees journals charge a fee in order to make articles publicly available. This model trades a restriction on who is able to read with a restriction on who is able to author. With APC costs for a typical journal at somewhere over $2000 US, we are asking for more than many researchers’ monthly salaries—a sum that, in some places, is an enviable amount of money for an entire research project.

To make matters worse, we have seen that other parts of the world—notably Latin America—have embraced a model of OA that does not rely on APCs. This means that when a researcher from the Global North submits to a journal from Latin America, Latin American universities and governments cover the costs of its public availability, but when a researcher from Latin America submits to a journal in the Global North, it is again Latin American governments that need to send money to the North. The problems are more far-reaching, and they are not getting any better with initiatives like Plan S continuing to favor this model. But this offers one example of how academic journal publishing—including the open access we worked so hard to achieve—continues to reinforce global inequalities in ways that are very much contrary to the spirit and substance of the SDGs.

Part 3: Where we go from here

So where do we go from here? Fortunately, there are those who are already calling for a broader, more integrated approach to open scholarship. I am encouraged by the work of the Open and Collaborative Science Development Network (OCSDNet), which released a manifesto that calls for: 1) an expansion of the term open science to open and collaborative science, and 2) a model of open and collaborative science that seriously considers cognitive justice, equitable collaboration, inclusive infrastructures, sustainable development, and a paradigm OCSDNet describes as “situated openness.” I believe their work should serve as a starting point for any policy framework that seeks to promote openness.

I can also point to the Panama Declaration on Open Science, made by an ad-hoc group of advocates and civil society organizations. It adopts some of the principles of the OCSDNet manifesto and describes a need to consider a holistic approach to open science that includes participation from citizens and civil society organizations, among others.

Thinking more broadly means, at least to me, that open scholarship policies can grapple with the fact that academia is still plagued with issues of inequality and discrimination—based on race, gender, sexual orientation, ability, and more—and then, on top of that, epistemological discrimination. This inequality flows through academia. It extends beyond its bounds to the public it is supposed to serve. It extends across institutions, and certainly across countries. We can see it in how resources are allocated, whose knowledge is privileged, what type of work is welcome, and who is even allowed to participate—as in the case of APCs.

"Inequality flows through academia. It extends beyond its bounds to the public it is supposed to serve. It extends across institutions, and certainly across countries."

So, I propose that, just as the drafters of the SDGs resisted disentangling the goals and targets from each other and instead emphasized that the need to consider their interconnections, so must we—proponents of open scholarship—resist separating out the issues plaguing academia from the goals of open scholarship itself.

At the very least, policies pushing for greater open scholarship need to be careful to avoid deepening historical and structural power structures that—and here I am quoting Leslie Chan, one of the original signatories of the BOAI Declaration—“positioned former colonial masters as the centres of knowledge production, while relegating former colonies to peripheral roles, largely as suppliers of raw data.”

I hope that seeing how things have panned out with open access can offer us some guidance here. In some sense, it is great to have had that learning opportunity, because the opportunity for open scholarship is far greater than it ever was for open access. Open scholarship is a mode of thinking and working that lends itself well to addressing the global politics of knowledge production, and the historical exclusion and marginalization of diverse perspectives. It offers us the opportunity to change in thinking about more than just how and where we publish our work. However, I’m sorry to tell those of you who are looking for a quick solution, that it will certainly require more than adding a few carrots for researchers to count and measure how “open” they are.

Here, please forgive a lengthy quote from Kathleen Fitzpatrick’s book Generous Thinking, where she says: “All those analytics lead us back to the cycle we’re currently trapped in: competition, austerity, increasing privatization, and a growing divide between the university and the public it is meant to serve. Breaking that cycle and establishing a new mode of both thinking and structuring the role of the university in contemporary culture requires nothing short of a paradigm shift.” She goes on to add: “What I am arguing for is thus not a disruption but a revolution in our thinking, one specifically focused on demanding the good that higher education can create.”

I believe open scholarship policies can and should have bringing about that change in thinking as their primary aim.

Okay, with my time almost up, or possibly already over, allow me to close by bringing it back to the incentives and motivations that I started with. Perhaps I am too naïve or optimistic, but I fundamentally believe that the people who go into this line of work—myself included—are already on board with the notion of serving the public good. Policies and incentives might encourage us to share our work more broadly and can help nudge us along to specific practices, but they will never be our guiding force. That is, I don’t think we should be worried about incentivizing scholars to want to serve society. But we do need to make policies that transform the role of the university so that serving the public good is first and foremost on the minds of faculty, and serves as a compass guiding how they work.

This change is not just one that universities need to make. It also requires that the infrastructures, organizations, and societies around our universities shift their priorities and expectations of the role of scholarship.

As we think about what open scholarship policies we want, we need to do far more than support the targets laid out in the SDGs. We need to craft policies that put the university and scholarship in direct service to society again. Doing so will directly address all of the SDG goals.

Are you ready to take up the challenge?

Understanding and Improving Incentives for Open Access

Keynote presented by Juan Pablo Alperin at Atla Annual on June 13, 2019.

Overview

- Introduction

- The case for open access

- Barriers to open access

- The role of incentives

- What do we know about incentives?

- The review, promotion, and tenure project

- Digging into open access

- Digging into the impact factor

- Who creates these documents?

- Summarizing

Introduction

Before I begin, I would like to acknowledge that much of the work I am going to be drawing upon here today is made possible by the incredible team at the Scholarly Communications Lab. Normally these thank yous go at the end, but I like to give them at the beginning when everyone is still paying attention.

I also need to thank and acknowledge the team behind the review, promotion, and tenure project, which includes Erin McKiernan, Meredith Niles, and Lesley Schimanski, who have led this project as much as I have. It is all too easy to stand here and take credit, but it is a credit that I need to share with all of them—and with so many others.

Finally, before I really get going, I feel compelled to tell you a little bit more about myself and my background. You may have noticed that I am neither a librarian, nor a theologian. I am first and foremost a father (you can say hello to my son Milo in the front row), and after that, I am a scholar of scholarly communications. I never intended to pursue a career in academia, let alone one on the esoteric topic of research communication. How I fell upon this topic is a longer story, one for another day, but a few key elements of that story are important for the topic at hand.

The first is that I am originally from Argentina, but my family immigrated to Canada when I was 11 years old. I have an aunt and uncle who are university professors of geology at a good-sized public university in Argentina. When I visited them in the year 2000, I set them up with the proxy to the University of Waterloo library, along with my password. It turns out that, as a 20 year-old student, I had better access to the journals they needed than they did. I did not realize it, nor appreciate the larger implications of it then, but this was my first exposure to the real need for open access. My aunt and uncle have had my university passwords ever since.

The second part of the story is just the larger scale version of the first. In 2007, I was tasked with running workshops on the use of Open Journal Systems—the open source publishing platform of the Public Knowledge Project—throughout Latin America. My real goal at the time was to work in international development, but because I needed to pay off my student debt (and because my 27-year-old self was keen on traveling), I accepted. I ran the workshop series while programming my way around the continent, and, in doing so, had the opportunity to meet and work with journal editors from around the region. I realized that there were a lot of people working very hard to bring their journals online, and that they were doing so out of a desire to create and share knowledge. They were trying to strengthen the research culture in the region and, through that, improve their education system. Open access was important for their researchers, but also as a mechanism for them to succeed at increasing the circulation of the knowledge contained in the journals they published. I had unwittingly stumbled upon the dream international development job opportunity I was looking for.

Why do I think these two parts of the story are important? Because they are at the heart of why I have dedicated my career to advocating for open access. That is, this origin story serves to highlight the intersection between my personal values and goals and those of open access. My case may be an extreme one, but it is not unique. Those of us who work in academia—faculty and librarians alike—generally share these underlying values. We generally believe that society is best served when research and knowledge circulate broadly. Not everyone may not be willing to dedicate their entire academic career to understanding and promoting open access and encouraging the public’s use of research. But, as I am going to argue today, academics are already on board with wanting to make knowledge public; we just need to make sure we acknowledge that this is, in fact, something that we value.

The case for open access

Obviously, there have been many who have come before me in support of open access, and, in fact, a lot of ink has been spilled in building the case for OA. In earlier days, the idea of OA was seen as something radical. Something that faculty needed to be convinced of—not because they disagreed with sharing knowledge, but because the more formal notion of OA was new, and OA journals had not been around long enough to demonstrate their value.

Correspondingly, a lot of effort has gone into justifying the need for OA, including arguments for all of the following:

- citation advantage for authors: the idea that publishing OA leads to more citations

- ethical imperative: that it’s the right thing to do

- economic necessity: that it eases the financial burden on university budgets

- responsibility to tax-payer: that those who pay for research deserve access to it

- accelerated discovery: that easier access and fewer restrictions means faster science

- contribution to development: that OA, by bridging key knowledge divides, can help guide development

- and more…

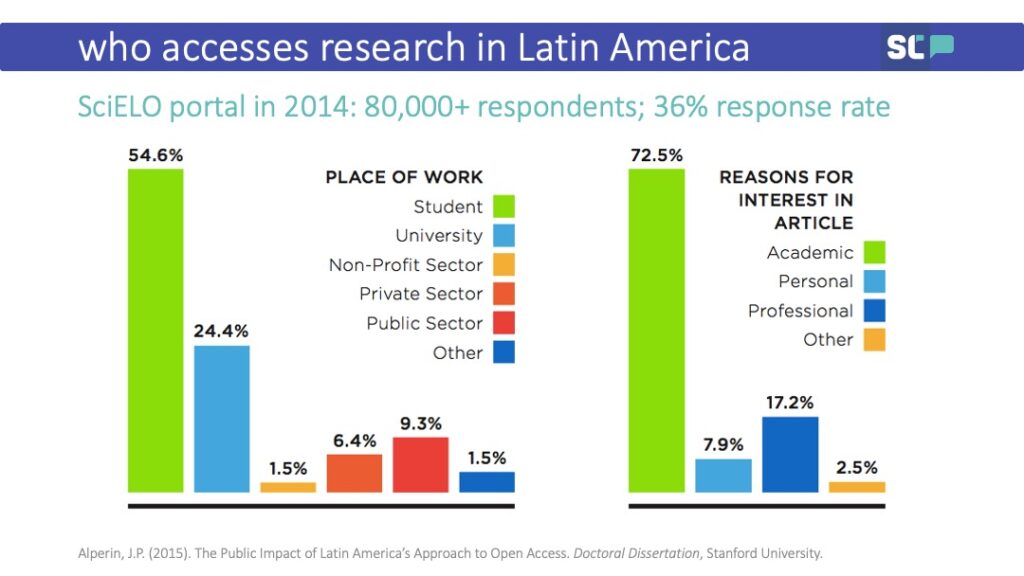

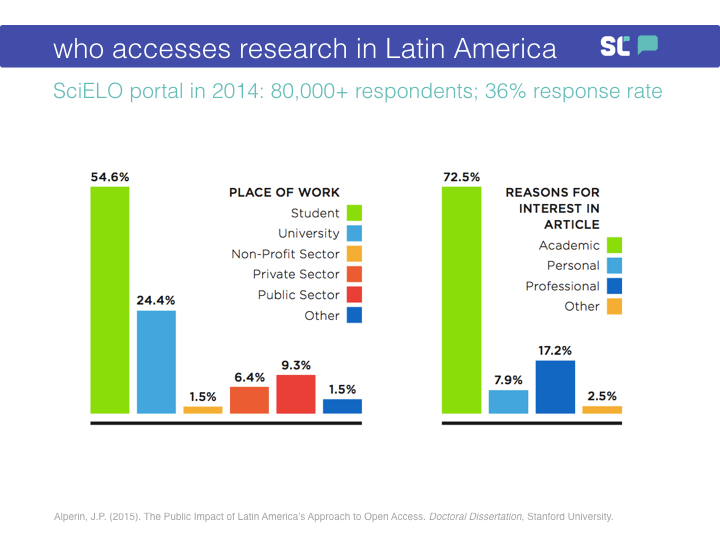

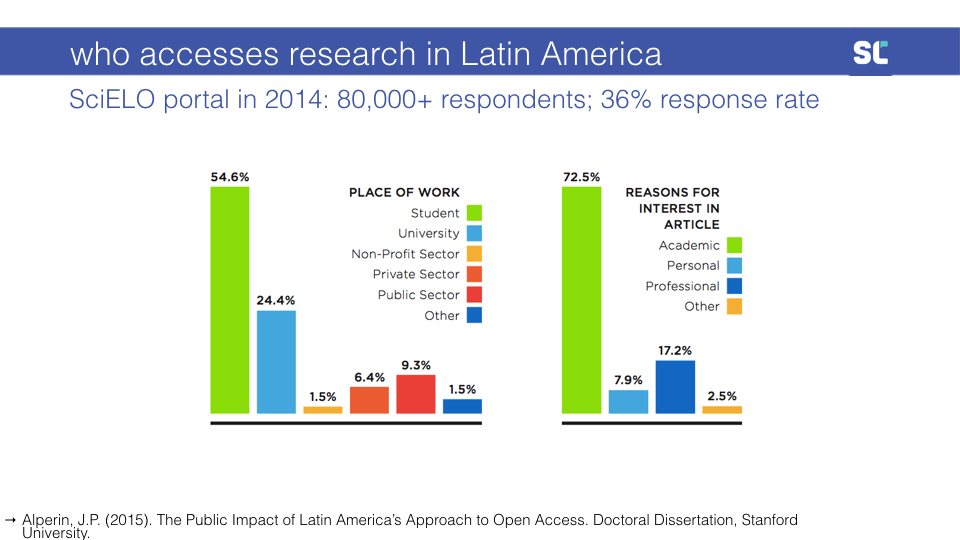

In my own work—and bringing it back to the case of Latin America—I ran a series of micro-surveys on one of the largest journal publishing portals in the region and found that between one fifth and one quarter of downloads of research articles came from outside of academia. That number varied a little depending on how exactly I asked the question. But, as you can see, students made up a significant portion of the downloads, whereas faculty (people working at universities) only made up a quarter. When I asked the question a different way, I found that around a quarter of the downloads came from people interested in research for reasons other than the academic one. While students and faculty make up about three quarters of the use, you’ll see that the public is also interested.

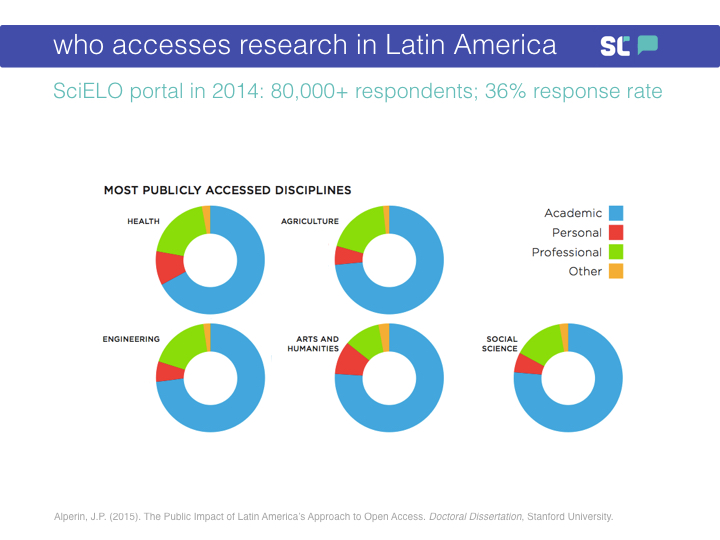

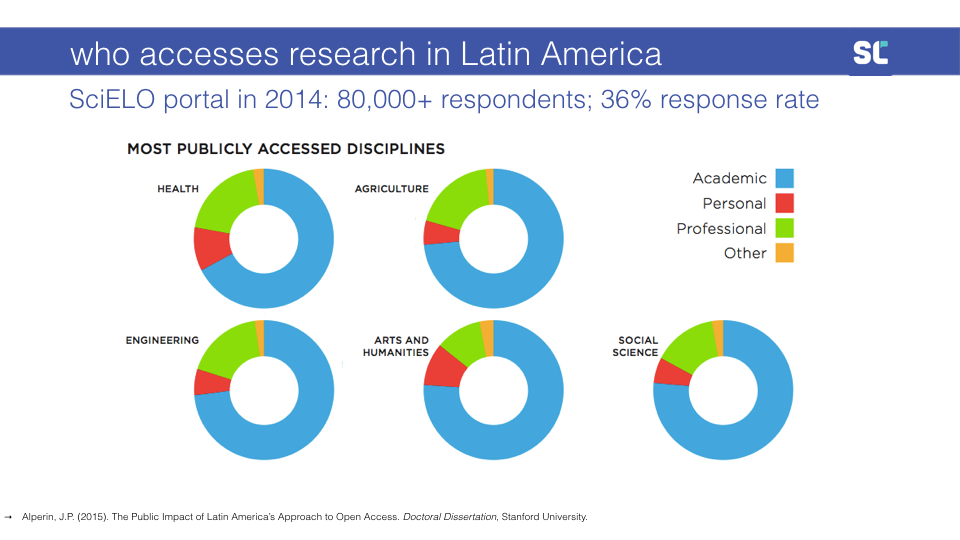

What is interesting is that this public demand—what I call Public Impact—is not limited to those fields where we would expect there to be public interest. Yes, when we look across disciplines, Health and Agriculture have the greatest non-academic interest, with a high proportion of that coming from those accessing for professional reasons. But we also find evidence of public impact in the Arts and Humanities—with a pretty even split between personal and professional interest—and in the Social Sciences—with more professional interest than personal.

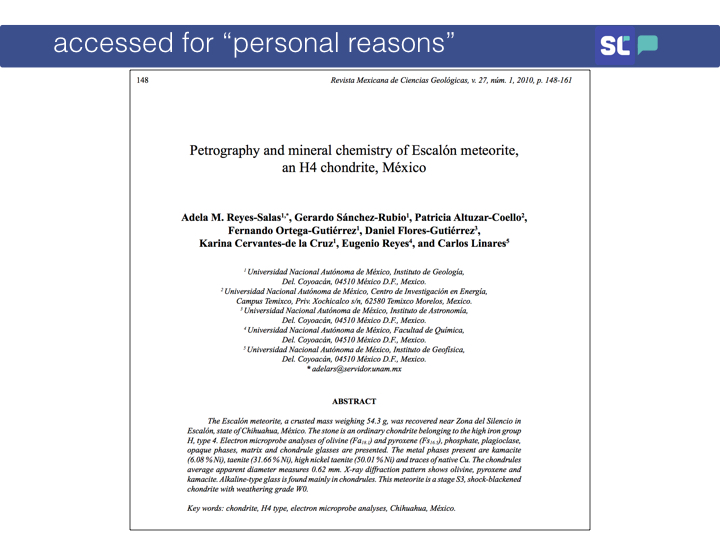

Let me show you just a couple of the papers for which there was reported “personal interest”:

In case you cannot read that, this paper is titled Petrography and mineral chemistry of Escalón meteorite, an H4 chondrite, México:

And one more, for good measure:

I cannot even pronounce the title of this paper, yet people access it for personal reasons.

So while I welcome efforts to translate and communicate science—which are important for all kinds of reasons—examples like this show that all research can have a public audience.

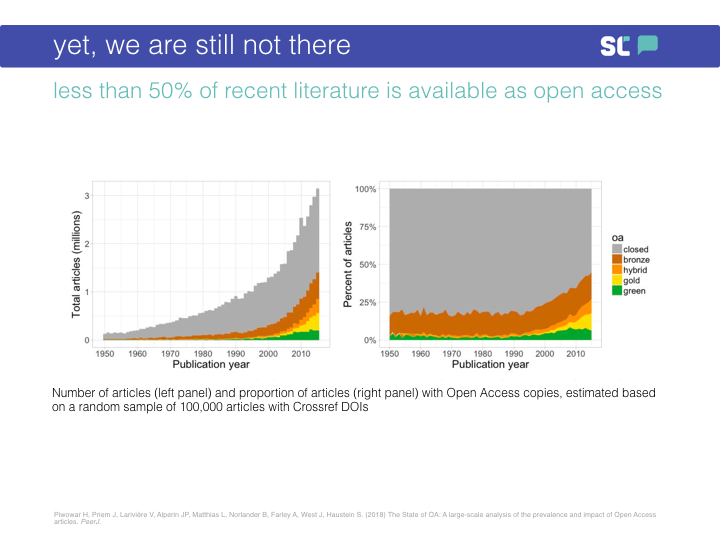

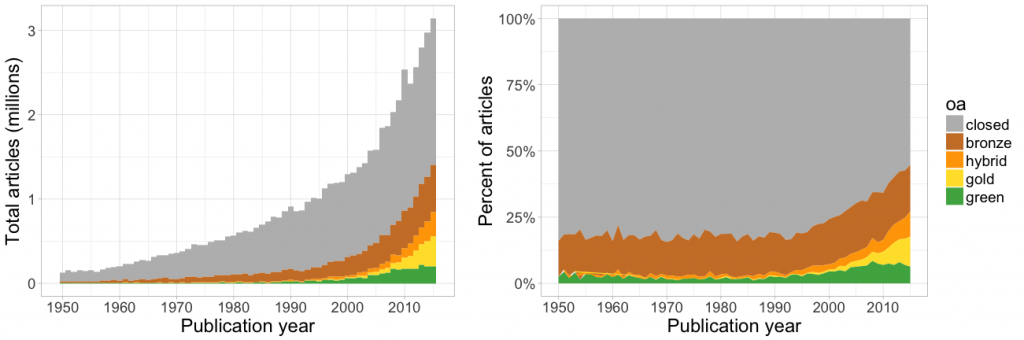

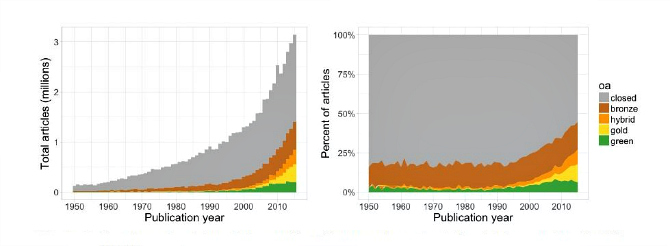

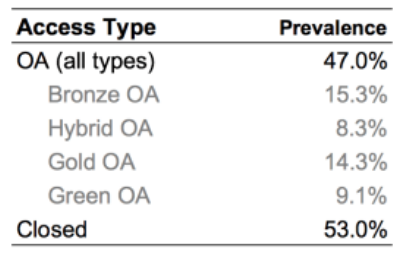

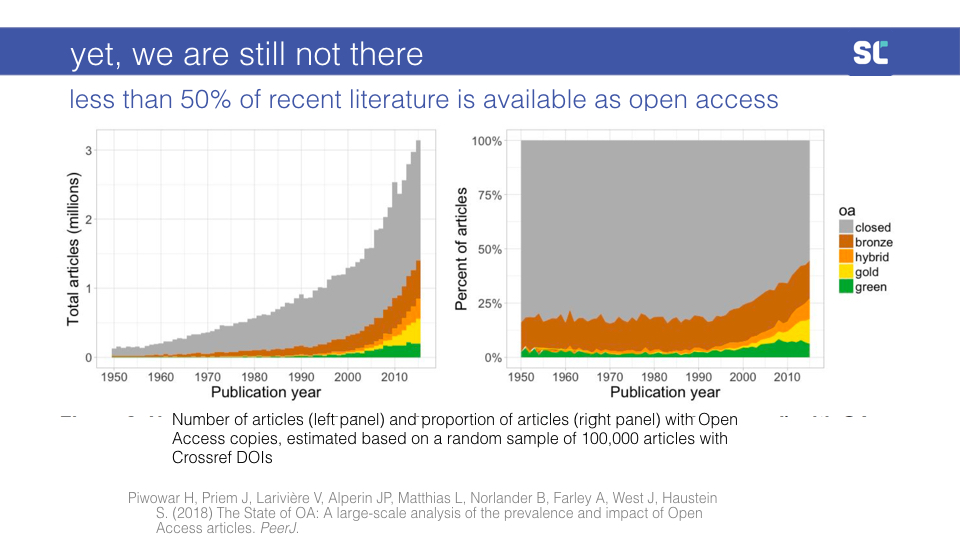

And yet, we are still not there. In 2018, we did a study using a tool and database called Unpaywall, and found that only 45% of the most recent literature is freely available to the public. This number is growing, both in the absolute number and as a percentage of total publications. But, still, we are barely making half of our publications publicly available.

Barriers to open access

We have plenty of evidence that the public values research that has been made open. We have even more compelling evidence that academics need and value access. So, shouldn’t we value providing that access?

Obviously, the reasons for why we do not have access are complex. They are social, individual, and structural at the same time, and they also have a technical component. As with any complex social system, these barriers are also deeply intertwined with one another.

One such narrative goes as follows:

- subscription publishing is very profitable

- alternative models are less so

- many established journals rely on subscriptions

- there are increasing pressures to publish more

- nobody has time for careful evaluation

- reliance on journal brands and impact factors benefits established journals

- and so we go back to #1.

There is so much at play here that I could talk for a full hour on just these challenges and we would still not be done. I am sure that you have touched on many of these throughout the week. At play here are fundamental questions of the value of public education, the market logic that has permeated the academy, the vertical integration efforts of companies like Elsevier, the challenges in the academic labour market, and so on.

The role of incentives

But I noticed a trend in all my time attending scholarly communication gatherings, sitting on the board of SPARC, and traveling. It seemed as though every conversation aimed at tackling these challenges came down to the same issue: incentives.

These conversations are taking place at all levels.

For example, the 2017 G7 Science Ministers’ Communiqué reads as follows: “We agree that an international approach can help the speed and coherence of this transition [towards open science], and that it should target in particular two aspects. First, the incentives for the openness of the research ecosystem: the evaluation of research careers should better recognize and reward Open Science activities.”

Another example, this time from an article by 11 provosts (2012) offering specific suggestions for campus administrators and faculty leaders on how to improve the state of academic publishing: “Ensuring that promotion and tenure review are flexible enough to recognize and reward new modes of communicating research outcomes.”

And finally, from research conducted at the University of California at Berkeley’s Center for Studies in Higher Education (2010): “there is a need for a more nuanced academic reward system that is less dependent on citation metrics, slavish adherence to marquee journals and university presses, and the growing tendency of institutions to outsource assessment of scholarship to such proxies.”

What do we know about incentives?

There is some existing research into the role of incentives in faculty publishing decisions.

For example, a three-year study by Harley and colleagues (2010) into faculty values and behaviors in scholarly communication found that “The advice given to pre-tenure scholars was quite consistent across all fields: focus on publishing in the right venues and avoid spending too much time on public engagement, committee work, writing op-ed pieces, developing websites, blogging, and other non-traditional forms of electronic dissemination.”

Related work by Björk (2004) similarly concludes that the tenure system “naturally puts academics (and in particular the younger ones) in a situation where primary publishing of their best work in relatively unknown open access journals is a very low priority.”

But most of this work—and we did a pretty comprehensive literature review—is based on surveys and interviews, mostly within a single university or a single discipline, and is relatively limited in scope.

The Review, Promotion, and Tenure Project

Our approach was different. We wanted to look at what was written in the actual documents that govern the Review, Promotion, and Tenure process.

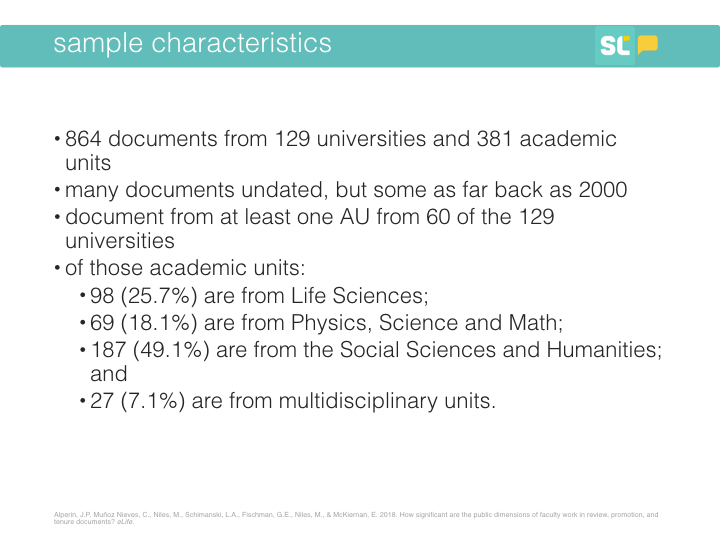

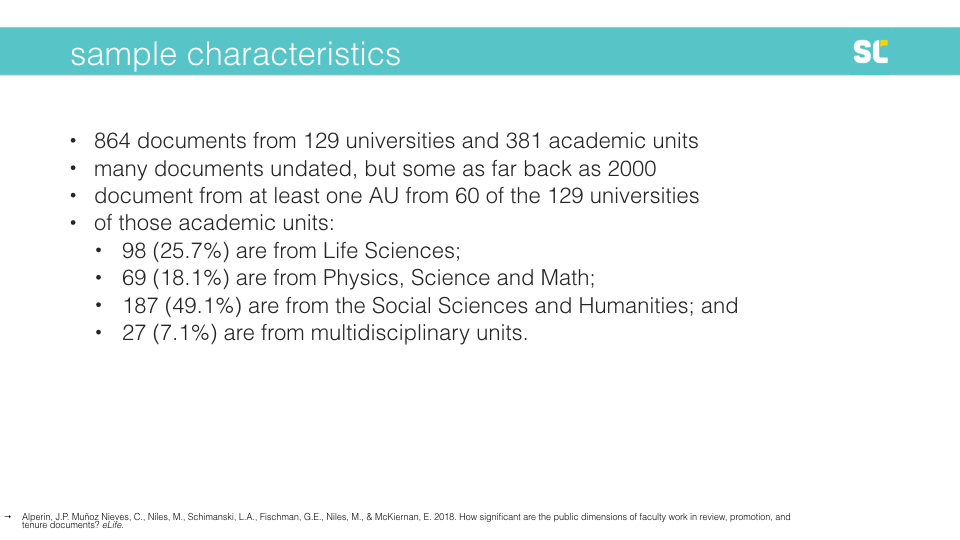

We ended up collecting 864 documents from 129 universities and 381 academic units. We chose universities by doing a stratified random sample across institution type using the Carnegie Classification of Institutions for the US, and the Maclean’s Ranking for Canada. Many of these documents were undated, but some dated as far back as 2000.

We collected documents from the academic units of 60 of the 129 universities in our sample:

- 98 (25.7%) from the Life Sciences;

- 69 (18.1%) from Physics, Science, and Math;

- 187 (49.1%) from the Social Sciences and Humanities; and

- 27 (7.1%) from multidisciplinary units.

Which means we have, as far as we know, the most representative set of documents that govern the RPT process. We were then able to do text searches on these documents for terms or groups of terms of interest, such as “open access” or various language related to citation metrics.

Does anyone want to take a guess at how many mentioned open access?

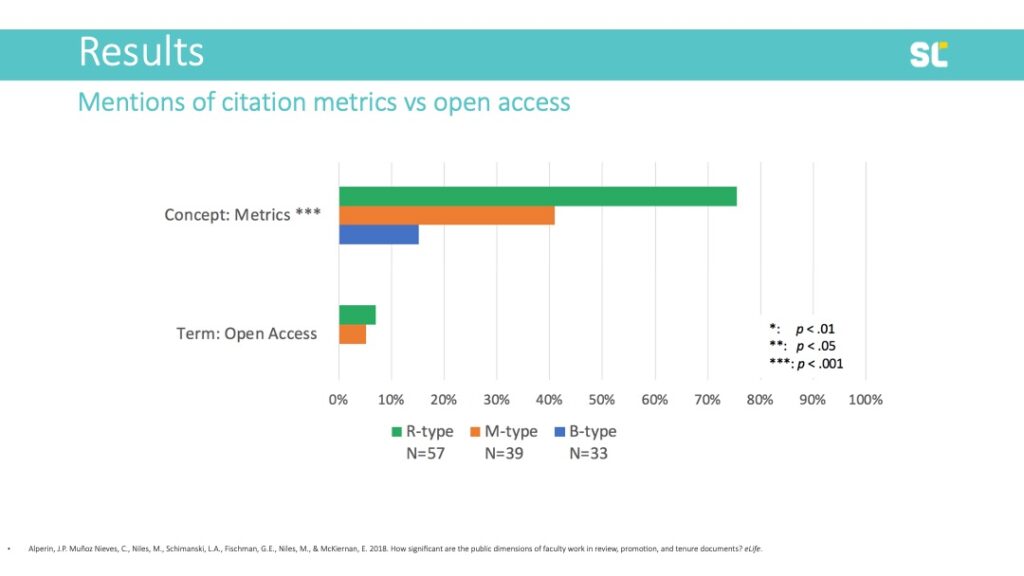

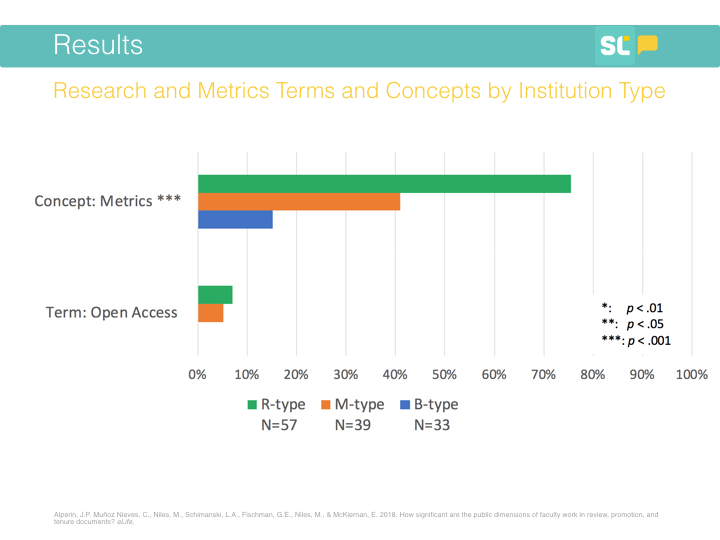

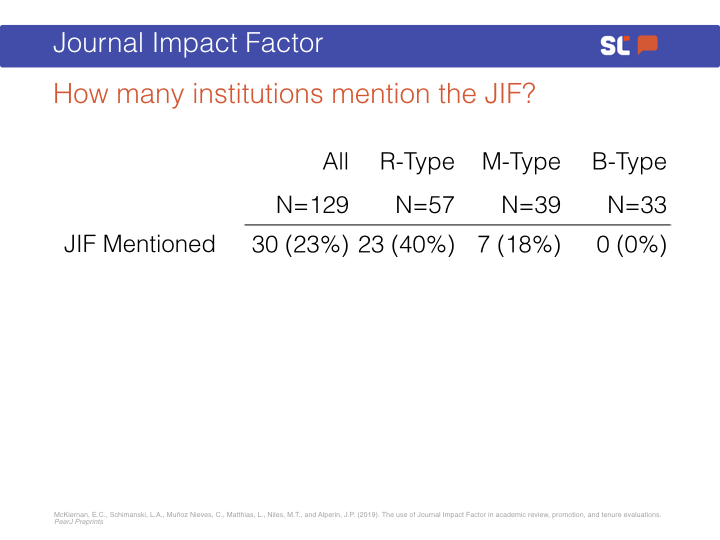

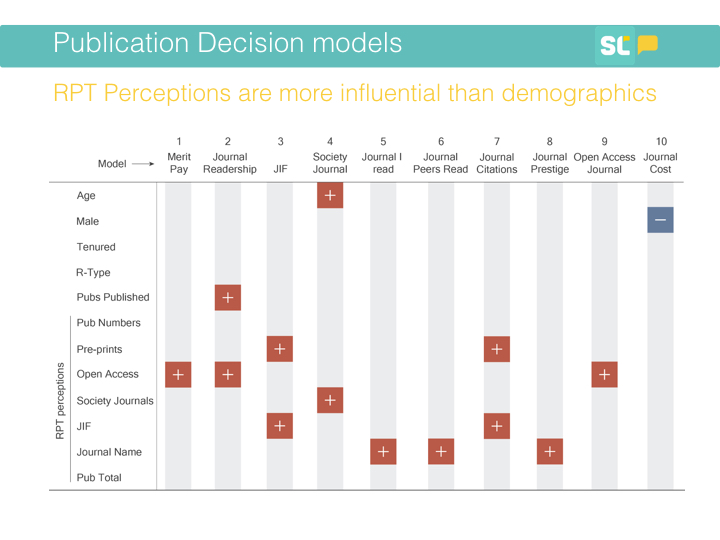

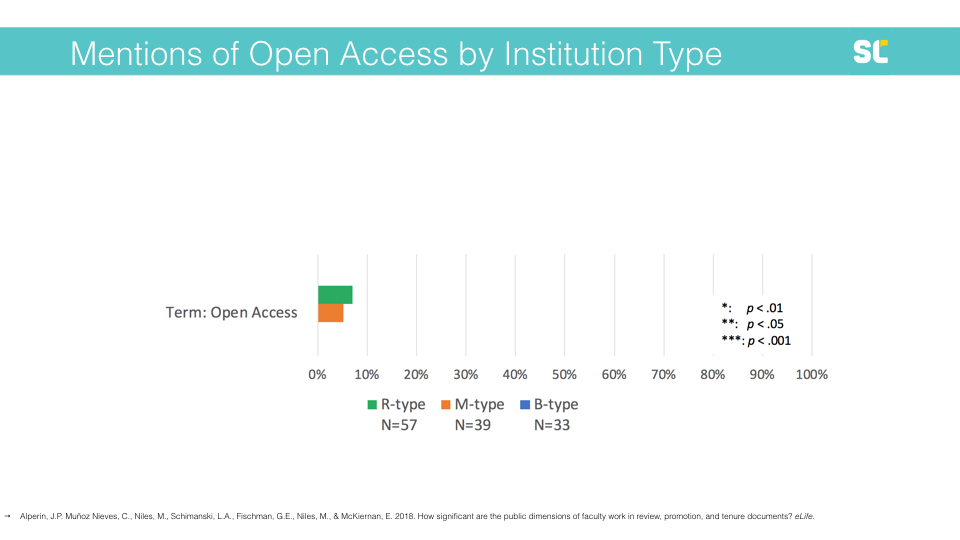

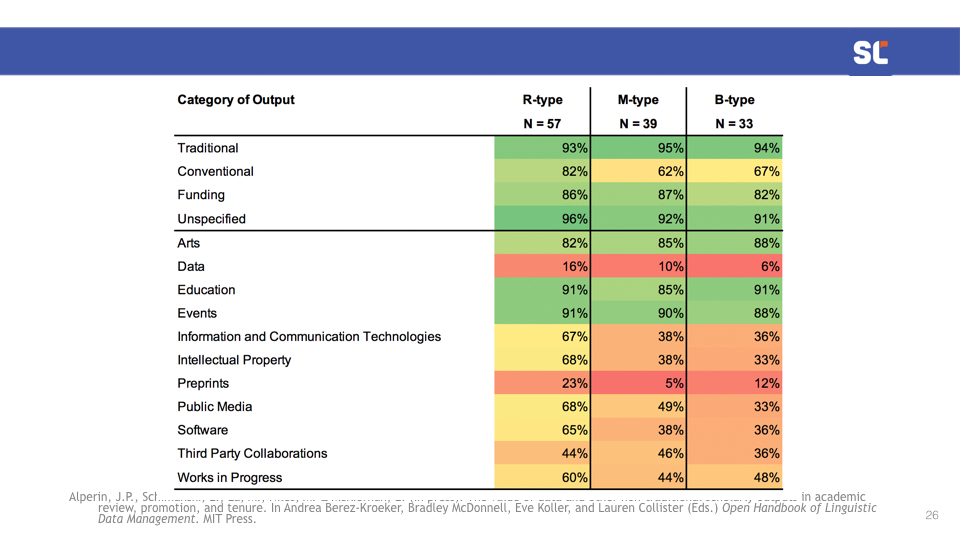

Above, you’ll see how often OA is mentioned by various kinds of academic institutions, including those focused on doctoral programs (i.e., research intensive; R-type), those that predominantly grant master’s degrees (M-type), and those that focus on undergraduate programs (i.e., baccalaureate; B-type).

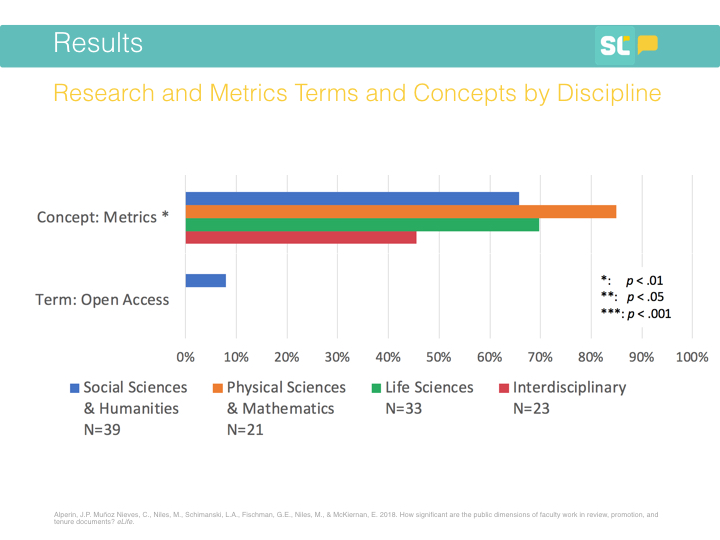

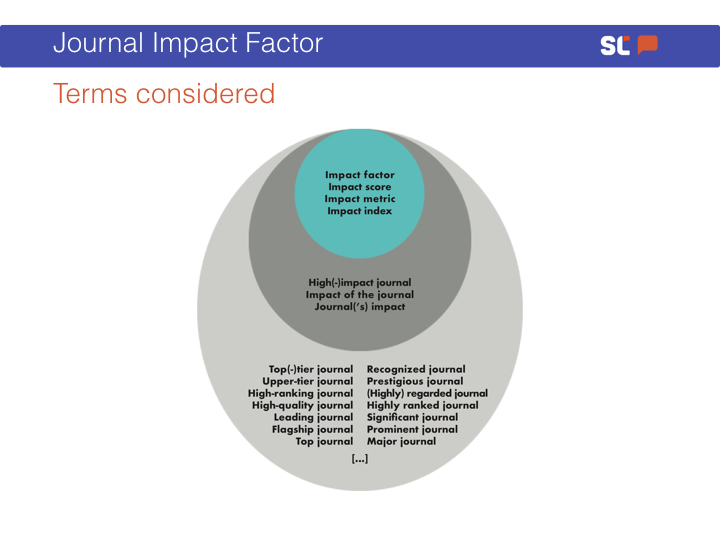

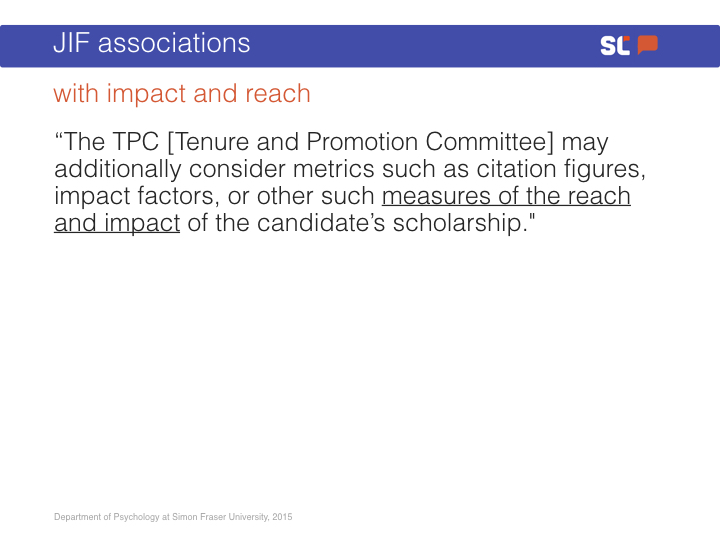

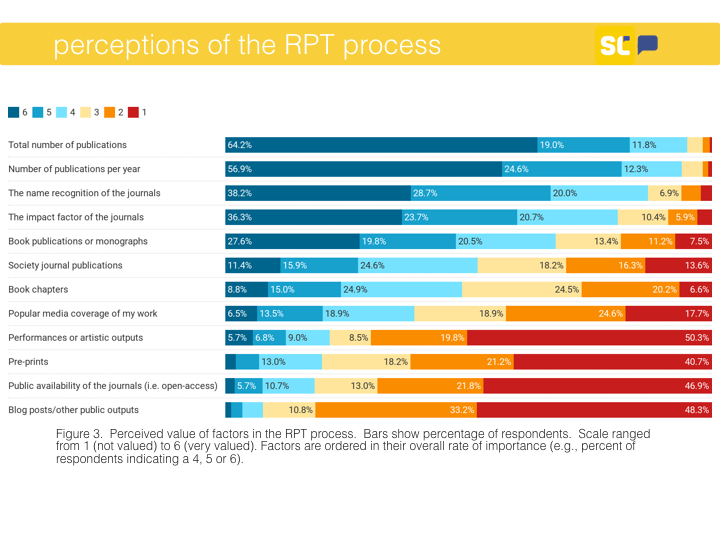

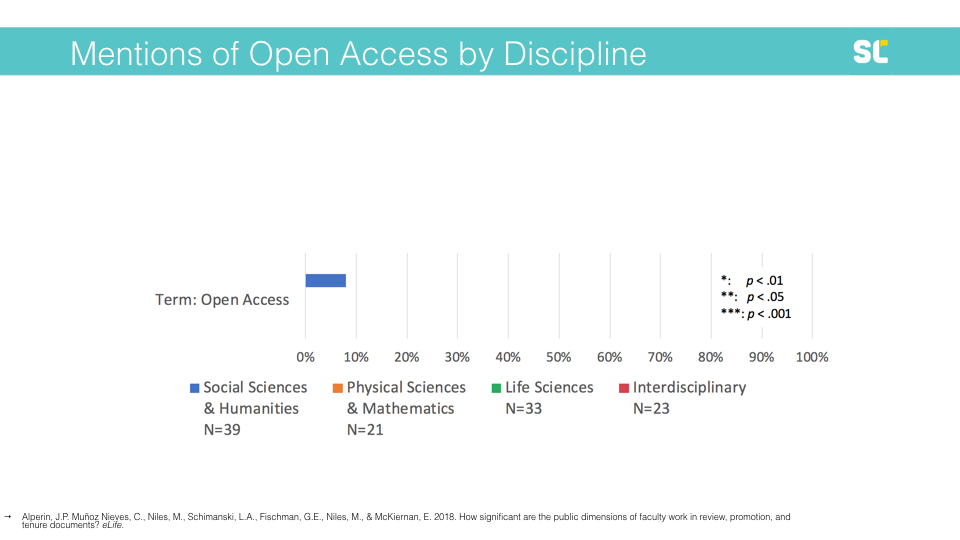

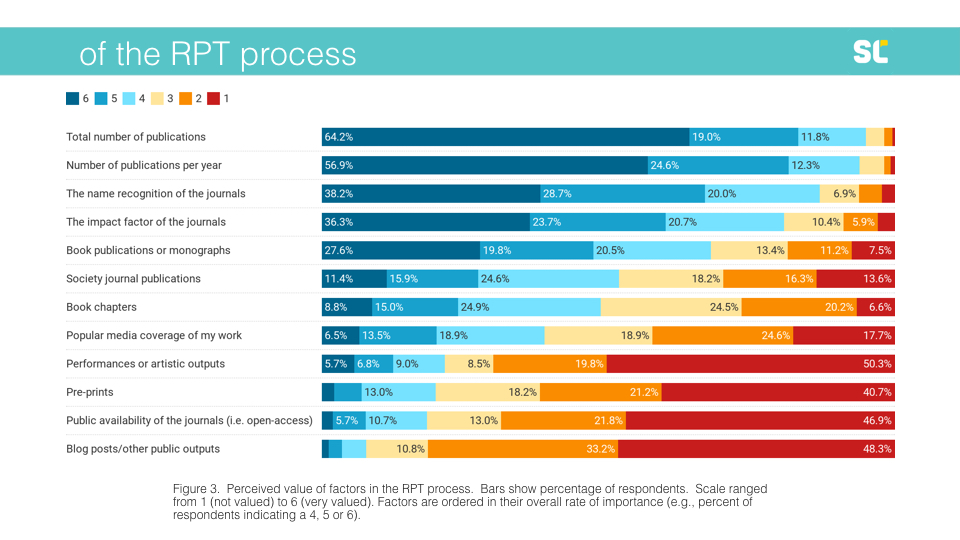

What we found is that OA was mentioned by only around 5% of institutions. Just to give you a point of comparison, citation metrics, such as the journal impact factor or the h-index, were found in the documents of 75% of the R-type institutions.

When we look by discipline, we find the mentions of OA are exclusively found in units related to the social sciences and humanities.

Digging into open access

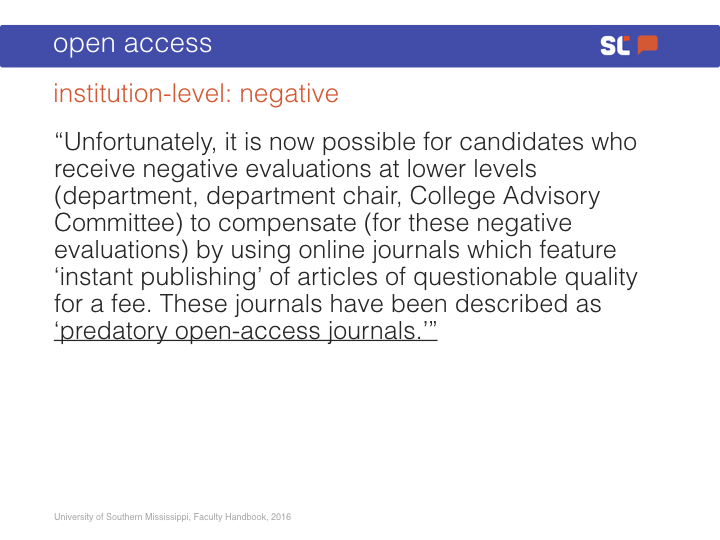

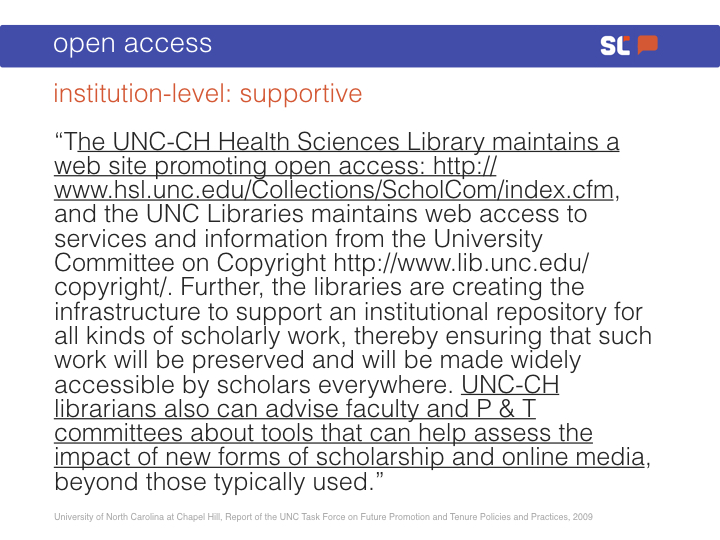

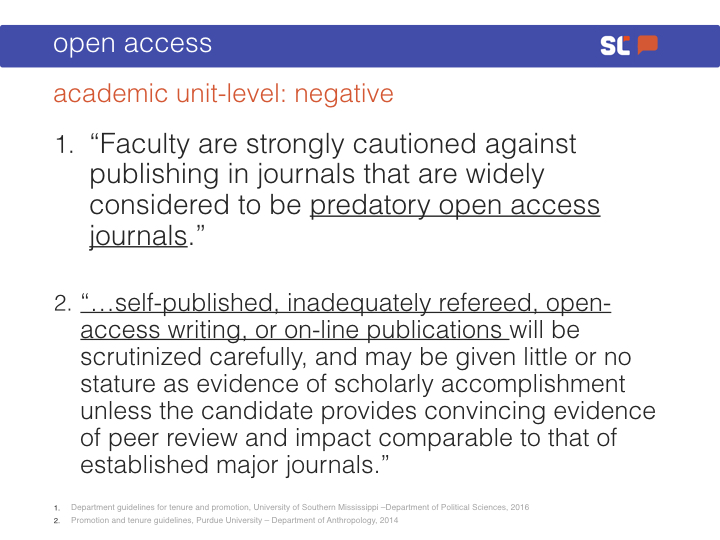

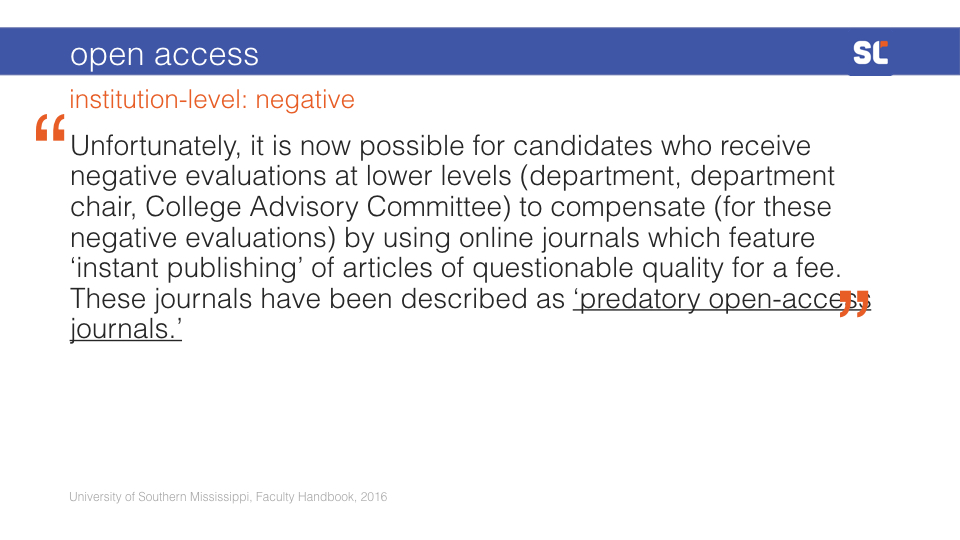

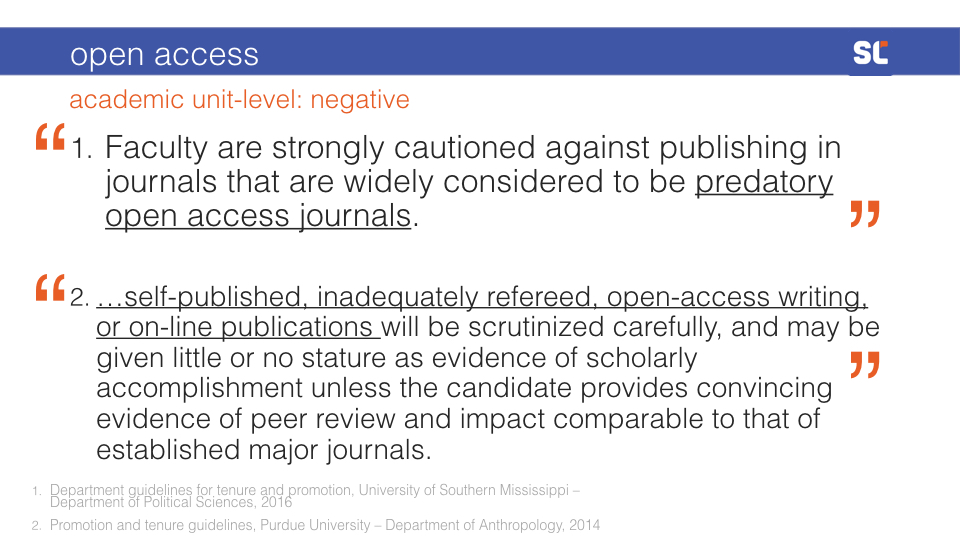

Now, some of you may be thinking that 5% is not so bad. If you are feeling encouraged that it is mentioned at all, please hold on a moment. Here are some examples of mentions of open access.