Keynote presented by Juan Pablo Alperin at Atla Annual on June 13, 2019.

Overview

- Introduction

- The case for open access

- Barriers to open access

- The role of incentives

- What do we know about incentives?

- The review, promotion, and tenure project

- Digging into open access

- Digging into the impact factor

- Who creates these documents?

- Summarizing

Introduction

Before I begin, I would like to acknowledge that much of the work I am going to be drawing upon here today is made possible by the incredible team at the Scholarly Communications Lab. Normally these thank yous go at the end, but I like to give them at the beginning when everyone is still paying attention.

I also need to thank and acknowledge the team behind the review, promotion, and tenure project, which includes Erin McKiernan, Meredith Niles, and Lesley Schimanski, who have led this project as much as I have. It is all too easy to stand here and take credit, but it is a credit that I need to share with all of them—and with so many others.

Finally, before I really get going, I feel compelled to tell you a little bit more about myself and my background. You may have noticed that I am neither a librarian, nor a theologian. I am first and foremost a father (you can say hello to my son Milo in the front row), and after that, I am a scholar of scholarly communications. I never intended to pursue a career in academia, let alone one on the esoteric topic of research communication. How I fell upon this topic is a longer story, one for another day, but a few key elements of that story are important for the topic at hand.

The first is that I am originally from Argentina, but my family immigrated to Canada when I was 11 years old. I have an aunt and uncle who are university professors of geology at a good-sized public university in Argentina. When I visited them in the year 2000, I set them up with the proxy to the University of Waterloo library, along with my password. It turns out that, as a 20 year-old student, I had better access to the journals they needed than they did. I did not realize it, nor appreciate the larger implications of it then, but this was my first exposure to the real need for open access. My aunt and uncle have had my university passwords ever since.

The second part of the story is just the larger scale version of the first. In 2007, I was tasked with running workshops on the use of Open Journal Systems—the open source publishing platform of the Public Knowledge Project—throughout Latin America. My real goal at the time was to work in international development, but because I needed to pay off my student debt (and because my 27-year-old self was keen on traveling), I accepted. I ran the workshop series while programming my way around the continent, and, in doing so, had the opportunity to meet and work with journal editors from around the region. I realized that there were a lot of people working very hard to bring their journals online, and that they were doing so out of a desire to create and share knowledge. They were trying to strengthen the research culture in the region and, through that, improve their education system. Open access was important for their researchers, but also as a mechanism for them to succeed at increasing the circulation of the knowledge contained in the journals they published. I had unwittingly stumbled upon the dream international development job opportunity I was looking for.

Why do I think these two parts of the story are important? Because they are at the heart of why I have dedicated my career to advocating for open access. That is, this origin story serves to highlight the intersection between my personal values and goals and those of open access. My case may be an extreme one, but it is not unique. Those of us who work in academia—faculty and librarians alike—generally share these underlying values. We generally believe that society is best served when research and knowledge circulate broadly. Not everyone may not be willing to dedicate their entire academic career to understanding and promoting open access and encouraging the public’s use of research. But, as I am going to argue today, academics are already on board with wanting to make knowledge public; we just need to make sure we acknowledge that this is, in fact, something that we value.

The case for open access

Obviously, there have been many who have come before me in support of open access, and, in fact, a lot of ink has been spilled in building the case for OA. In earlier days, the idea of OA was seen as something radical. Something that faculty needed to be convinced of—not because they disagreed with sharing knowledge, but because the more formal notion of OA was new, and OA journals had not been around long enough to demonstrate their value.

Correspondingly, a lot of effort has gone into justifying the need for OA, including arguments for all of the following:

- citation advantage for authors: the idea that publishing OA leads to more citations

- ethical imperative: that it’s the right thing to do

- economic necessity: that it eases the financial burden on university budgets

- responsibility to tax-payer: that those who pay for research deserve access to it

- accelerated discovery: that easier access and fewer restrictions means faster science

- contribution to development: that OA, by bridging key knowledge divides, can help guide development

- and more…

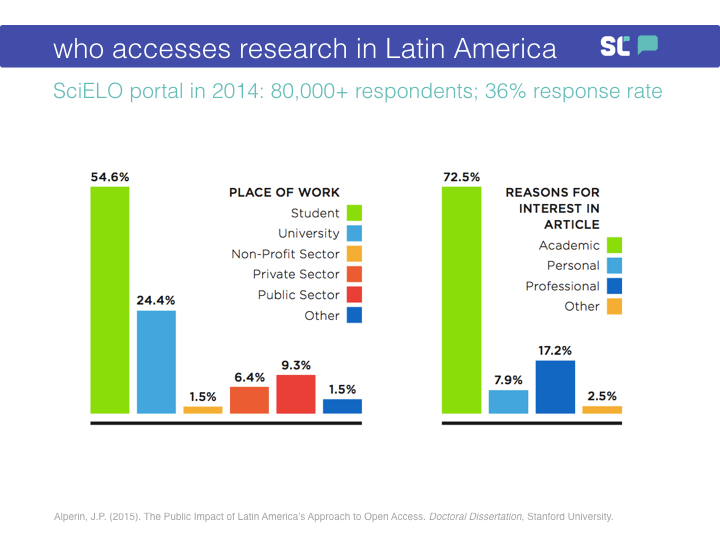

In my own work—and bringing it back to the case of Latin America—I ran a series of micro-surveys on one of the largest journal publishing portals in the region and found that between one fifth and one quarter of downloads of research articles came from outside of academia. That number varied a little depending on how exactly I asked the question. But, as you can see, students made up a significant portion of the downloads, whereas faculty (people working at universities) only made up a quarter. When I asked the question a different way, I found that around a quarter of the downloads came from people interested in research for reasons other than the academic one. While students and faculty make up about three quarters of the use, you’ll see that the public is also interested.

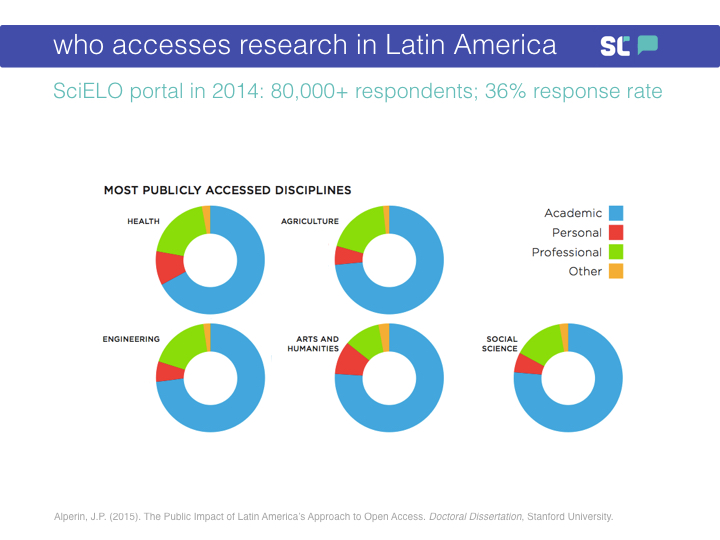

What is interesting is that this public demand—what I call Public Impact—is not limited to those fields where we would expect there to be public interest. Yes, when we look across disciplines, Health and Agriculture have the greatest non-academic interest, with a high proportion of that coming from those accessing for professional reasons. But we also find evidence of public impact in the Arts and Humanities—with a pretty even split between personal and professional interest—and in the Social Sciences—with more professional interest than personal.

Let me show you just a couple of the papers for which there was reported “personal interest”:

In case you cannot read that, this paper is titled Petrography and mineral chemistry of Escalón meteorite, an H4 chondrite, México:

And one more, for good measure:

I cannot even pronounce the title of this paper, yet people access it for personal reasons.

So while I welcome efforts to translate and communicate science—which are important for all kinds of reasons—examples like this show that all research can have a public audience.

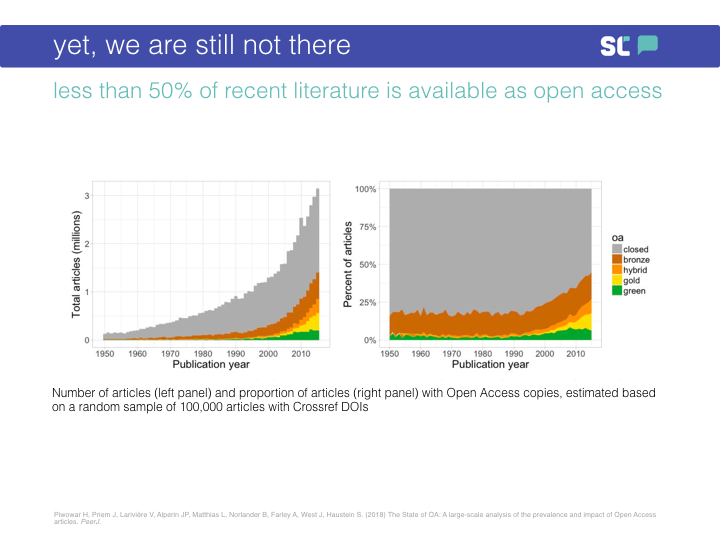

And yet, we are still not there. In 2018, we did a study using a tool and database called Unpaywall, and found that only 45% of the most recent literature is freely available to the public. This number is growing, both in the absolute number and as a percentage of total publications. But, still, we are barely making half of our publications publicly available.

Barriers to open access

We have plenty of evidence that the public values research that has been made open. We have even more compelling evidence that academics need and value access. So, shouldn’t we value providing that access?

Obviously, the reasons for why we do not have access are complex. They are social, individual, and structural at the same time, and they also have a technical component. As with any complex social system, these barriers are also deeply intertwined with one another.

One such narrative goes as follows:

- subscription publishing is very profitable

- alternative models are less so

- many established journals rely on subscriptions

- there are increasing pressures to publish more

- nobody has time for careful evaluation

- reliance on journal brands and impact factors benefits established journals

- and so we go back to #1.

There is so much at play here that I could talk for a full hour on just these challenges and we would still not be done. I am sure that you have touched on many of these throughout the week. At play here are fundamental questions of the value of public education, the market logic that has permeated the academy, the vertical integration efforts of companies like Elsevier, the challenges in the academic labour market, and so on.

The role of incentives

But I noticed a trend in all my time attending scholarly communication gatherings, sitting on the board of SPARC, and traveling. It seemed as though every conversation aimed at tackling these challenges came down to the same issue: incentives.

These conversations are taking place at all levels.

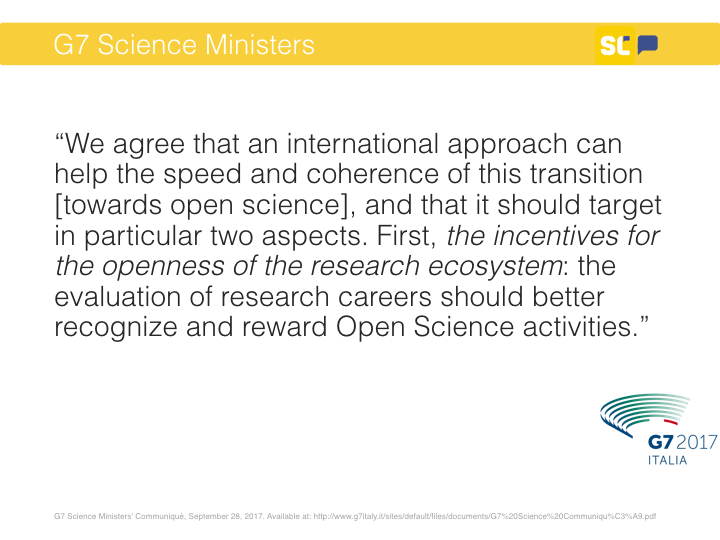

For example, the 2017 G7 Science Ministers’ Communiqué reads as follows: “We agree that an international approach can help the speed and coherence of this transition [towards open science], and that it should target in particular two aspects. First, the incentives for the openness of the research ecosystem: the evaluation of research careers should better recognize and reward Open Science activities.”

Another example, this time from an article by 11 provosts (2012) offering specific suggestions for campus administrators and faculty leaders on how to improve the state of academic publishing: “Ensuring that promotion and tenure review are flexible enough to recognize and reward new modes of communicating research outcomes.”

And finally, from research conducted at the University of California at Berkeley’s Center for Studies in Higher Education (2010): “there is a need for a more nuanced academic reward system that is less dependent on citation metrics, slavish adherence to marquee journals and university presses, and the growing tendency of institutions to outsource assessment of scholarship to such proxies.”

What do we know about incentives?

There is some existing research into the role of incentives in faculty publishing decisions.

For example, a three-year study by Harley and colleagues (2010) into faculty values and behaviors in scholarly communication found that “The advice given to pre-tenure scholars was quite consistent across all fields: focus on publishing in the right venues and avoid spending too much time on public engagement, committee work, writing op-ed pieces, developing websites, blogging, and other non-traditional forms of electronic dissemination.”

Related work by Björk (2004) similarly concludes that the tenure system “naturally puts academics (and in particular the younger ones) in a situation where primary publishing of their best work in relatively unknown open access journals is a very low priority.”

But most of this work—and we did a pretty comprehensive literature review—is based on surveys and interviews, mostly within a single university or a single discipline, and is relatively limited in scope.

The Review, Promotion, and Tenure Project

Our approach was different. We wanted to look at what was written in the actual documents that govern the Review, Promotion, and Tenure process.

We ended up collecting 864 documents from 129 universities and 381 academic units. We chose universities by doing a stratified random sample across institution type using the Carnegie Classification of Institutions for the US, and the Maclean’s Ranking for Canada. Many of these documents were undated, but some dated as far back as 2000.

We collected documents from the academic units of 60 of the 129 universities in our sample:

- 98 (25.7%) from the Life Sciences;

- 69 (18.1%) from Physics, Science, and Math;

- 187 (49.1%) from the Social Sciences and Humanities; and

- 27 (7.1%) from multidisciplinary units.

Which means we have, as far as we know, the most representative set of documents that govern the RPT process. We were then able to do text searches on these documents for terms or groups of terms of interest, such as “open access” or various language related to citation metrics.

Does anyone want to take a guess at how many mentioned open access?

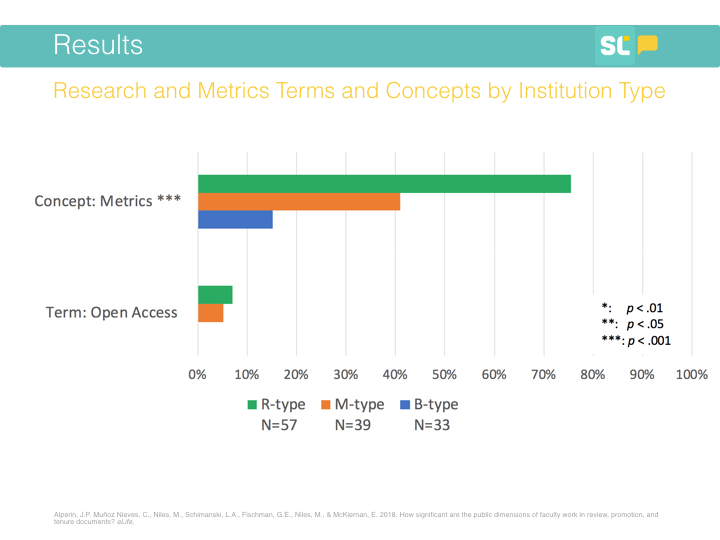

Above, you’ll see how often OA is mentioned by various kinds of academic institutions, including those focused on doctoral programs (i.e., research intensive; R-type), those that predominantly grant master’s degrees (M-type), and those that focus on undergraduate programs (i.e., baccalaureate; B-type).

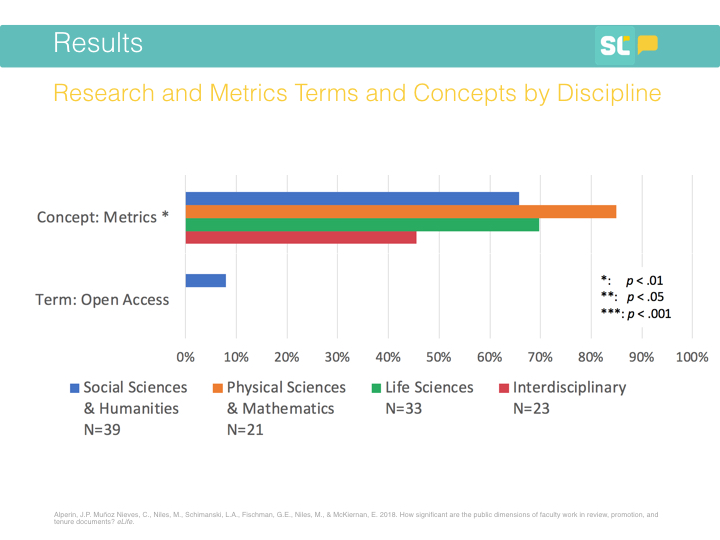

What we found is that OA was mentioned by only around 5% of institutions. Just to give you a point of comparison, citation metrics, such as the journal impact factor or the h-index, were found in the documents of 75% of the R-type institutions.

When we look by discipline, we find the mentions of OA are exclusively found in units related to the social sciences and humanities.

Digging into open access

Now, some of you may be thinking that 5% is not so bad. If you are feeling encouraged that it is mentioned at all, please hold on a moment. Here are some examples of mentions of open access.

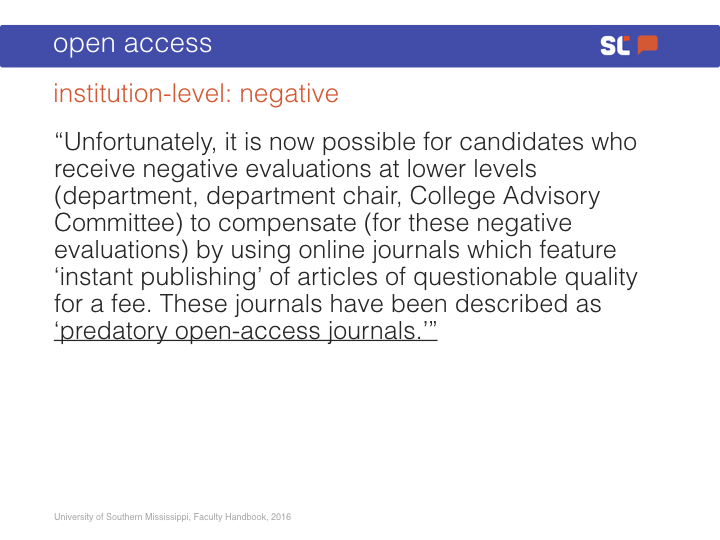

From the University of Southern Mississippi Faculty Handbook (2016): “Unfortunately, it is now possible for candidates who receive negative evaluations at lower levels (department, department chair, College Advisory Committee) to compensate [for these negative evaluations] by using online journals which feature ‘instant publishing’ of articles of questionable quality for a fee. These journals have been described as ‘predatory open-access journals.’”

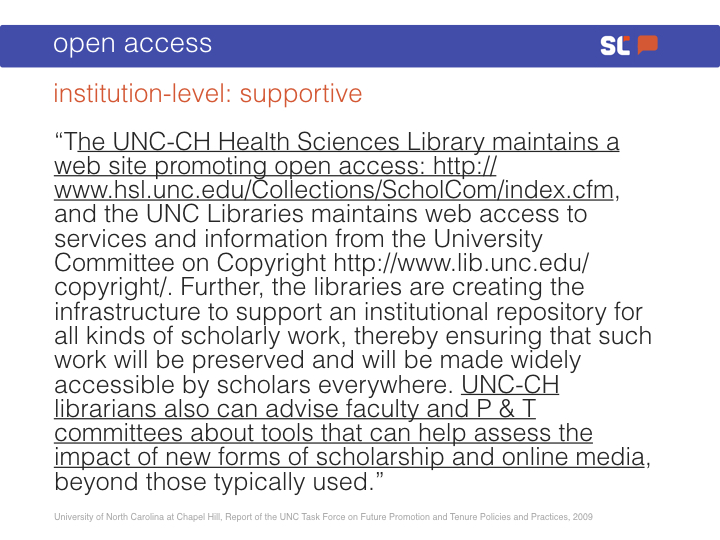

Now, for a Library Crowd pleaser, from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (2009): “The UNC‐CH Health Sciences Library maintains a web site promoting open access. Further, the libraries are creating the infrastructure to support an institutional repository for all kinds of scholarly work, thereby ensuring that such work will be preserved and will be made widely accessible by scholars everywhere. UNC‐CH librarians also can advise faculty and P & T committees about tools that can help assess the impact of new forms of scholarship and online media, beyond those typically used.”

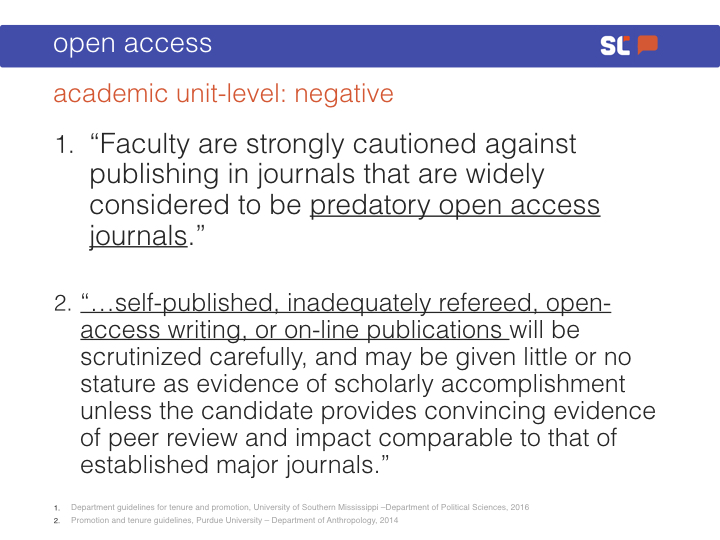

Another negative example from USM, this time from the Department of Political Sciences (2016): “Faculty are strongly cautioned against publishing in journals that are widely considered to be predatory open access journals.”

And from Purdue University’s Department of Anthropology (2014): “…self-published, inadequately refereed, open-access writing, or on-line publications will be scrutinized carefully, and may be given little or no stature as evidence of scholarly accomplishment unless the candidate provides convincing evidence of peer review and impact comparable to that of established major journals.”

And finally, a more neutral mention of OA, this time from the University of Central Florida (2014): “Open-access, peer-reviewed publications are valued like all other peer-reviewed publications.”

Digging into the impact factor

Okay, so the mentions of OA are not exactly great. Let’s dig into the mentions of one of the citation metrics: The Journal Impact Factor (JIF). If you recall, one of the challenges in moving towards OA is said to be that researchers are incentivized to publish in so-called “high-impact journals.” These tend to be the long-established ones, which have higher JIFs by virtue of having been around longer, which, in turn, leads to a self-perpetuating cycle of supporting these high-JIF journals. The JIF is also a metric based on citations, which measure the use of research within academia, but fail to capture the kind of public or pedagogical use I referred to earlier.

Beyond its potential role in diminishing the adoption of OA, the JIF is known to have many other issues, not least of which is that it gets used to evaluate articles, when it is, in fact, a journal-level metric.

So, perhaps the RPT documents would support improvements by mentioning the JIF in the same negative light as OA?

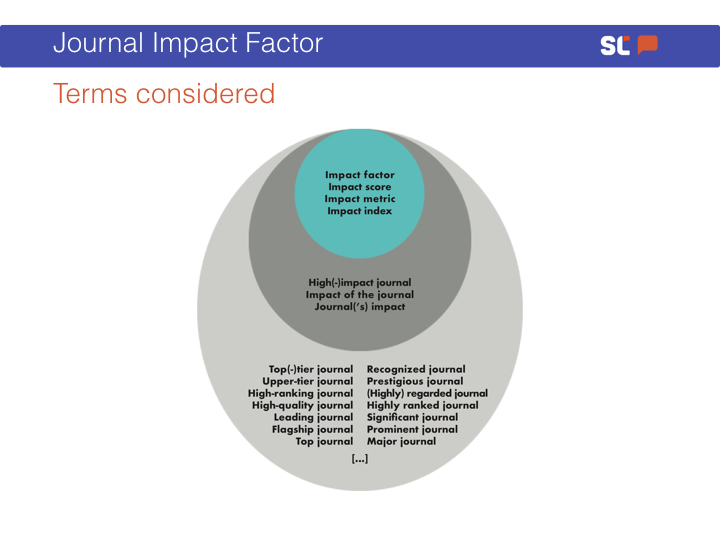

To examine mentions of the JIF in RPT documents, we focused on the terms in the inner two circles of the figure, above. Basically, this works out to terms that are similar to “Impact Score or Metric” and terms related to “Impact of the Journal”. There were a lot of other terms that might have been alluding to the JIF, which we chose to exclude because they were just not proximate enough.

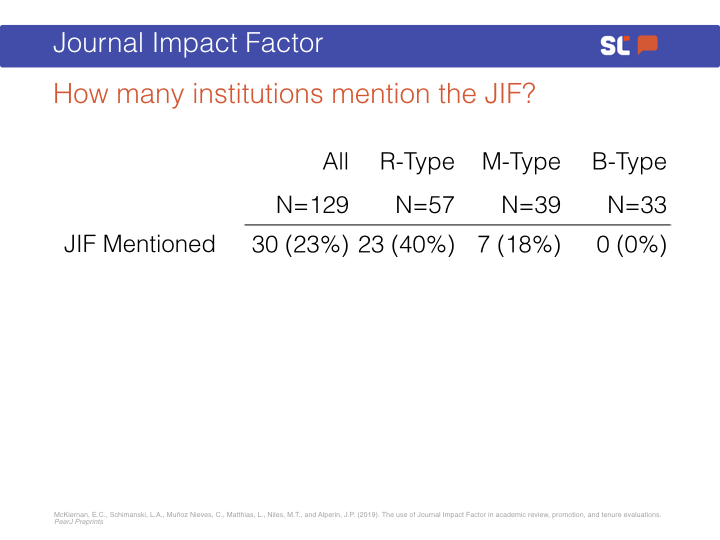

As you can see, 40% of the R-Type institutions mentioned the term—much more than those that mentioned open access.

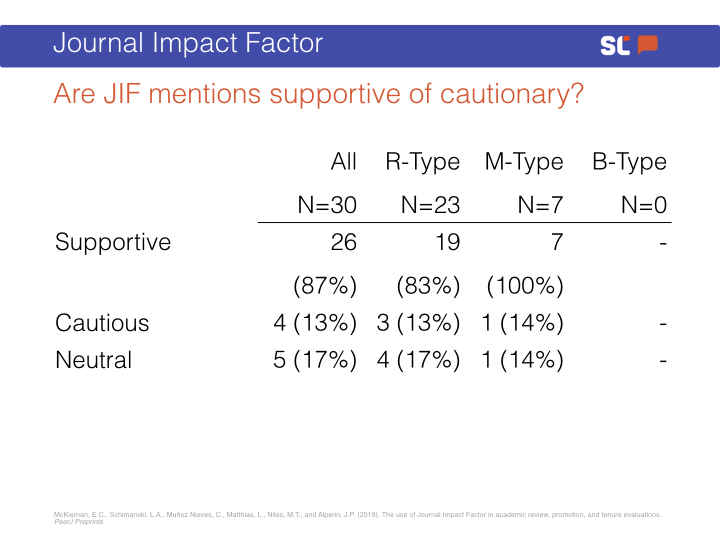

But now, the moment of truth. Were those mentions supportive, cautionary, or outright negative?

What we find is that well over 80% of the mentions of the JIF are actually supportive of its use. You may notice the numbers here do not add up to 100%. This is because it is possible for one institution to mention the JIF multiple times, in some cases in a supportive light and and in others less so. In those kinds of cases, we counted the institution in both categories.

One thing that you should note here is that there are no negative mentions. That is, we did not find a single instance where the use of the JIF was discouraged or outright forbidden.

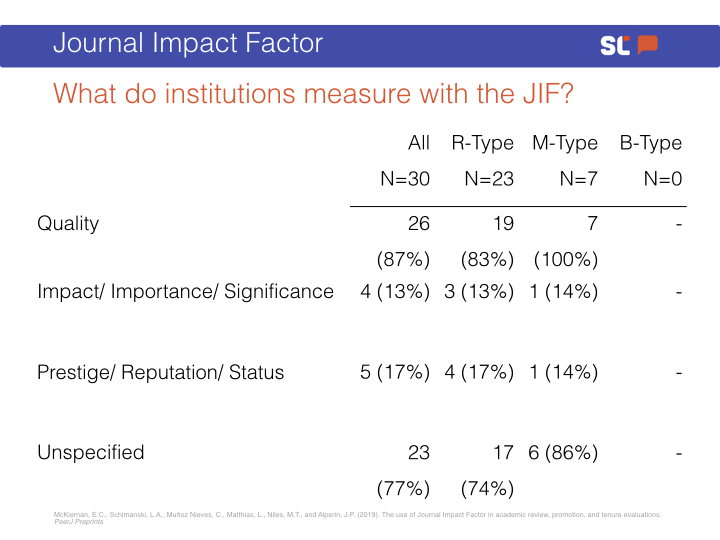

So, what do the documents say the JIF actually measures?

We find that over 80% of the mentions associate the JIF with quality. Again, here we should remember that by viewing the JIF as an important measure of quality, we are overlooking work that may be valuable to the public. Academic citations cannot capture the impact of scholarly work on non-academic audiences.

Allow me to show you a couple of examples:

From the Faculty of Science at the University of Alberta (2012): “Of all the criteria listed, the one used most extensively, and generally the most reliable, is the quality and quantity of published work in refereed venues of international stature. Impact factors and/or acceptance rates of refereed venues are useful measures of venue quality…”

Or this one, from the Department of Psychology at Simon Fraser University (2015): “The TPC [Tenure and Promotion Committee] may additionally consider metrics such as citation figures, impact factors, or other such measures of the reach and impact of the candidate’s scholarship.”

Who creates these documents?

So, where do we get these phrases? We write them ourselves, of course.

It is very easy to forget when discussing systemic challenges in academia that we are collegially governed. Although we are certainly subject to pressures from the outside, we make these rules ourselves. This makes understanding the factors that guide faculty decision making extremely important.

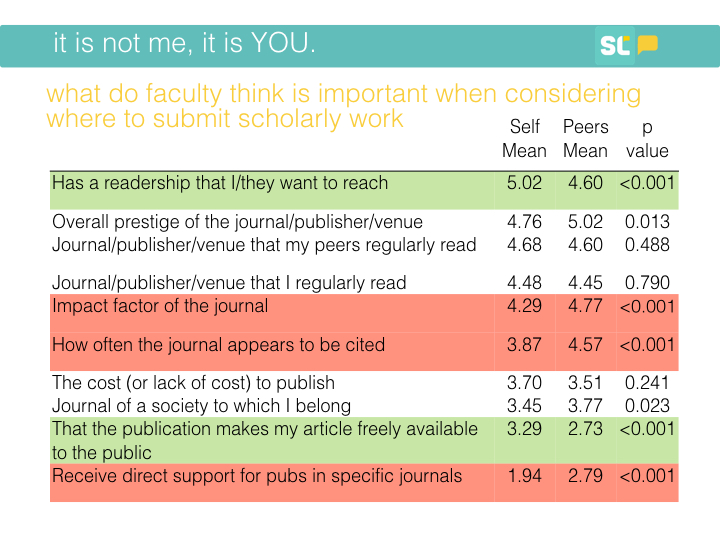

Here, if we look at the “self” column, you’ll see that journal readership is the top factor faculty say they value when deciding where to publish their work. Numbers 3 and 4, respectively, are submitting to a journal their peers read and submitting to one that they themselves regularly read.

Where it gets really interesting, however, is in the second column: what faculty think their peers value when considering where to submit. I’ve highlighted the items for which there are statistically significant differences between faculty members’ own publishing values and those they attribute to their peers. The rows in green are factors faculty say they value more than their peers; those in red are ones they say their peers value more.

What you’ll notice is that respondents value the journal’s audience and whether it makes its content freely available more than they think their peers do. On the flip side, they think their peers are more driven by citations and merit pay.

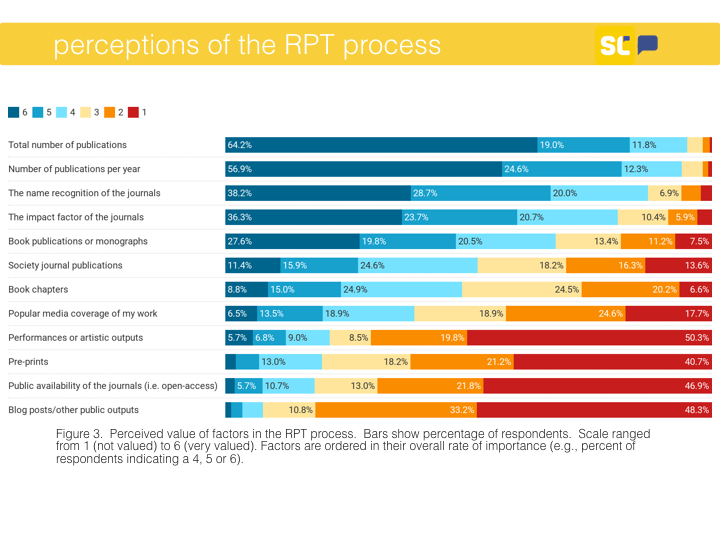

Next, we asked them about what they thought was valued in the RPT process, which is different from asking them how they make decisions on where to submit. Here, we also get a fairly cynical picture: faculty think their peers who sit on RPT committees value factors like total number of publications, publications per year, name recognition of journals, and JIFs.

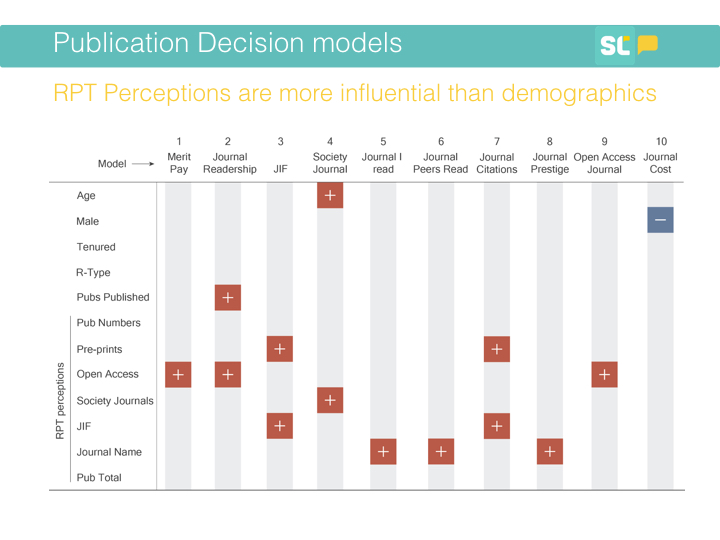

Then, we put all of this together using some statistical models. In this figure, you’ll see the factors influencing where faculty submit across the top, and the factors that might influence those factors down the first column. It paints a clear picture: faculty perceptions of the RPT process have a significant influence in many of the models—more so than demographic characteristics.

This means, if you look at model 9, for example, that a faculty member is more likely to consider whether a journal is open access if they believe that OA is valued in the RPT process. Similarly, they are more likely to care about the journal’s readership if they think that OA is valued in the RPT process.

Summarizing

It is perhaps unsurprising that faculty seem to be driven by readership and peer exposure to their work when deciding where to publish. But what is perhaps more surprising is the extent to which what our perceptions about what others value can shape those publications decisions, especially in terms of what we perceive is valued in the RPT process. That is, it seems that any shift away from the journal impact factor and the “slavish adherence to marquee journals” (as one paper put it) may be challenged not by faculty’s own values, but by the perception of their peer’s values, which are markedly different from their own.

Put plainly, our work on RPT suggests that faculty are guided by a perception that their peers are more driven by journal prestige, journal metrics (such as the JIF and journal citations), and money than they are, while they themselves value readership and open access of a journal more.

One place where faculty are getting these perceptions seems to be in the RPT documents, where we found that citation metrics, including the journal impact factor, are mentioned a significant number of times, especially at R-Type institutions. But this is not the only source, nor is it necessarily the most important one.

I began this talk by sharing some of my own reasons for caring about open access. I did this because, if there is one thing we can take away from this work, it’s that we need to be explicit about what we value. I know that many of you here today will support making all research publicly available, including your own and that of the faculty you work with. So, if you cannot change what is written in RPT documents to explicitly value OA, then I have the next best thing for you. Whenever you are at the next conference reception, instead of making small talk about the great weather we are having, I invite you begin a conversation by sharing with your colleague why access to research matters. Because it does.

Thank you.