ScholCommLab November Conference Blitz

It’s been a busy November for the ScholCommLab! This month, lab members took part in three conferences: the Canadian Science Policy Conference in Ottawa, the United Nations Open Science Conference, and the PKP 2019 International Scholarly Publishing Conference in Barcelona. For those who couldn’t make it, we’re sharing highlights from each event, right here on the blog.

Canadian Science Policy Conference

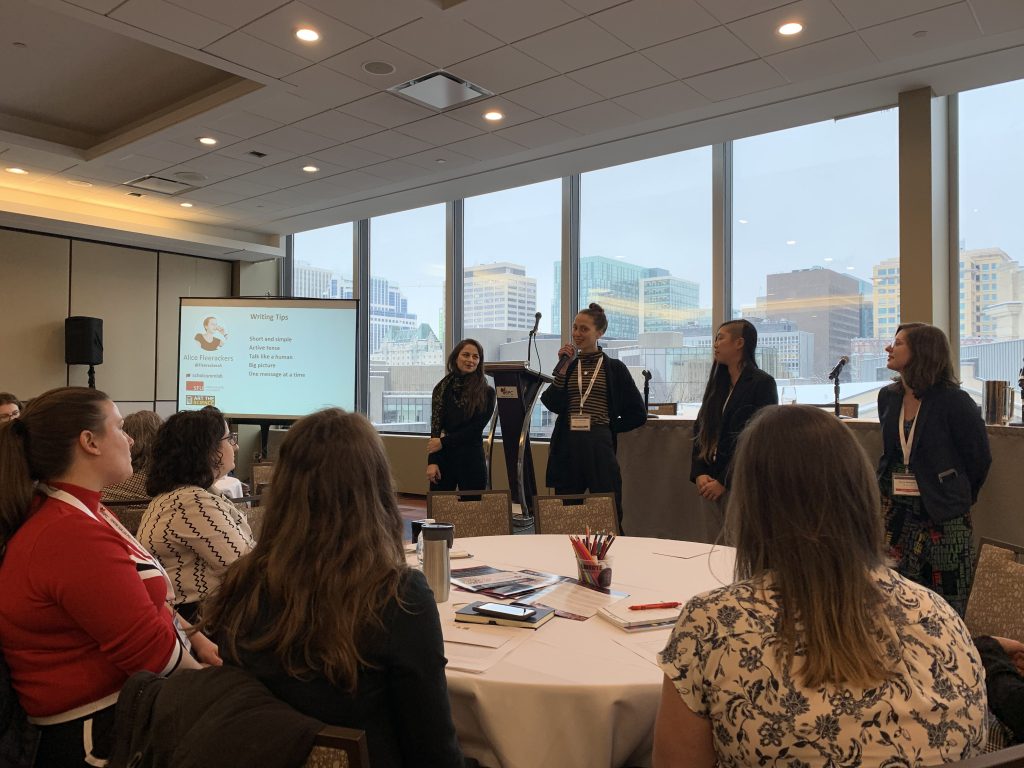

Taking place from November 14 to 16, CSPC is a wide-ranging conference aimed at “uniting stakeholders, strengthening dialogue, and enabling action” on top issues in Canadian science and technology policy. This year’s gathering was the biggest yet, with more than 800 participants and 40 panels. ScholCommLabbers Stefanie Haustein and Alice Fleerackers both attended, and each presented panels at the conference.

On November 14, Alice joined fellow science communicators Dorina Simoneov, Cat Lau, and Julia Krolik at CSPC 2019 for Creating SciComm: An Interactive Session Connecting Scientists, Policymakers, and the Public. Hands-on and participatory, their session engaged attendees in infographic-making—a visual communication activity aimed at bridging gaps between public and scientific knowledge.

Participants used paper, markers, glue sticks, and their own creativity to communicate research about four issues of public concern: climate change, artificial intelligence, genetically modified foods, and vaccinations. They collaborated and trouble-shooted to find simple ways to share complex scientific information. The completed infographics—all of which are publicly available online—are evidence of participants’ originality, enthusiasm, and willingness to connect with communities beyond the conference.

Stefanie’s panel, Mapping Dynamic Research Ecosystems: Tapping into New Indicators, Big Data and Emerging Technologies, centred on a very different science policy issue: the future of research analytics. This wide-ranging conversation was organized by the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada, moderated by Eric M. Meslin (Council of Canadian Academies), and featured speakers Elizabeth Boston, Xiaodan Zhu, and Adam Bradley, as well as Stefanie. Together, the panelists discussed the biggest challenges facing research data today, including how to understand and make use of the massive amounts of information available to us, the opportunities made possible by AI, the biases inherent in current bibliometrics practices, and more.

Stefanie also joined a provocative conversation at Fishing for Open Science Innovation: Should Canada Join Plan S? This fishbowl-style discussion invited conference attendees to “pitch new ideas, pose new questions, and debate the merits of Plan S for Canadian Science,” according to CSPC. Participants talked through pressing issues such as the feasibility of Plan S, the need for more collaborative and international open initiatives, and more. The conversation that followed revealed just as many questions as answers, as well as some promising opportunities for a more open future.

It was a busy couple of days, packed with presentations and networking. But in the midst of the conference madness, Alice and Stefanie joined uOttawa ScholCommLabbers Alyssa Jeffrey and Tristan Lamonica for some food, conversation, and, of course, a few selfies:

United Nations Open Science Conference

Taking place on November 19, this year’s United Nations Open Science Conference was organized by the UN Dag Hammarskjöld Library in collaboration with the Scholarly Publishing and Academic Resources Coalition (SPARC). It brought together open advocates, policymakers, library directors, and early career researchers from across the world to discuss open science and open research at a global level. This year’s theme, “Towards Global Open Science: Core Enabler of the UN 2030,” focused the conversation on the 2030 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and the role open initiatives can play in meeting them.

ScholCommLab co-director Juan Pablo Alperin gave the opening keynote, setting the tone for the talks and workshops that would follow. His presentation, “Policies & Incentives for Open Scholarly Communication,” centred on the role incentives can play in promoting open scholarship. Building on lab research into academic career incentives, but pushed conference attendees to consider other incentives as well.

“Researchers are driven by the big picture, the idea that they’re contributing to something greater,” he explained. “We need to start focusing on a discourse that goes above individualistic motivations and consider the public role of researchers and universities.” Drawing on work by Kathleen Fitzpatrick on the power of generous thinking, he argued that the move toward true open scholarship will require a more “generous” approach—one that positions the university more broadly within society.

PKP 2019 International Scholarly Publishing Conference

Finally, the lab wrapped up a packed fall at the Public Knowledge Project’s bi-annual conference in Barcelona. This international event engages participants in discussions and workshops about the latest in open access research and publishing. This year’s meeting kicked off on November 18 with a two-day working sprint, followed by a day of workshops and two days of presentations from members of the community.

For Juan, PKP’s Associate Faculty Director of Research, it offered a valuable opportunity to connect with a global community of individuals and organizations who are contributing to open access publishing. At the conference, he offered a brief overview of some of the projects that the ScholCommLab has been working on as part of its ongoing collaboration with PKP, all of which explore how scholarly knowledge is created, circulated, and used in academia and beyond.

Happy to be home

After a whirlwind fall, it’s great to have everyone in the lab back at their (respective) homes. We’ll be back at it in the spring, but, for now, we’re enjoying a well-deserved break. Keep an eye out for our upcoming talks and events, and see you in 2020!

For more, check out these video interviews with Stefanie Haustein and Alice Fleerackers at CSPC 2019.

Altmetrics researchers: Time to take another look at Facebook, you’ve been missing something

“I hope that the kind of altmetrics research that has been going on lately is dying out,” says Asura Enkhbayar, in a conversation about the ScholCommLab’s latest preprint. “It is time to move beyond crunching numbers of whatever is easiest and to look for the activity we care about on social media.”

The preprint—which he published last week with Stefanie Haustein, Germana Barata, and Juan Pablo Alperin—investigated how much of research shared on Facebook is hidden from public view. Although wishing some altmetrics research “dead” may be a little strong, the results show that there are important questions that have been overlooked by the altmetrics community.

In this blog post, we highlight key findings from the study and what they mean for scholarly communications and altmetrics research.

A long-overlooked platform

“Facebook has often been disregarded in altmetrics research,” Asura says. “It is seen as a platform that doesn’t produce real engagement with science.”

Previous studies have found that less than 8% of recent research is shared on the platform. This number is much lower than what is found on Twitter—a platform with a fraction of the number of users. As a result, many researchers avoid studying Facebook altogether, despite its massive user base.

But, as the team’s research reveals, Facebook’s “low” levels of engagement may have less to do with the platform itself, and more to do with how the data is collected.

“[Companies like] Altmetric only collect mentions of research that happen in Public Pages,” Juan explained in a recent Twitter thread. “This misses every time your friend, cousin, mom, or whoever posts a link on their Timeline!”

A novel approach to tracking research on Facebook

To capture these “invisible” research mentions, the team decided to try a different approach—one based on querying the API, rather than data mining.

“Companies like Plum Analytics use a similar approach” Asura says, “but we decided to take things further by looking at many different links URLs where the research article can be found.” He continues: “Science does not live in one place; there’s preprints, postprints, different variations—and we needed to capture engagement with as many of them as possible.”

"Science does not live in one place; there’s preprints, postprints, different variations—and we needed to capture engagement with as many of them as possible."—Asura Enkhbayar

This new technique complicated things considerably (so much so that the team ended up publishing a whole other article about the challenges involved). But it had the benefit of allowing the team to collect and consolidate the many different online versions of research shared on Facebook. Plus, it allowed them to explore—for the first time—research shared in Closed Groups, Timelines, and other private spaces inside Facebook.

More than half of research shared on Facebook is “invisible”

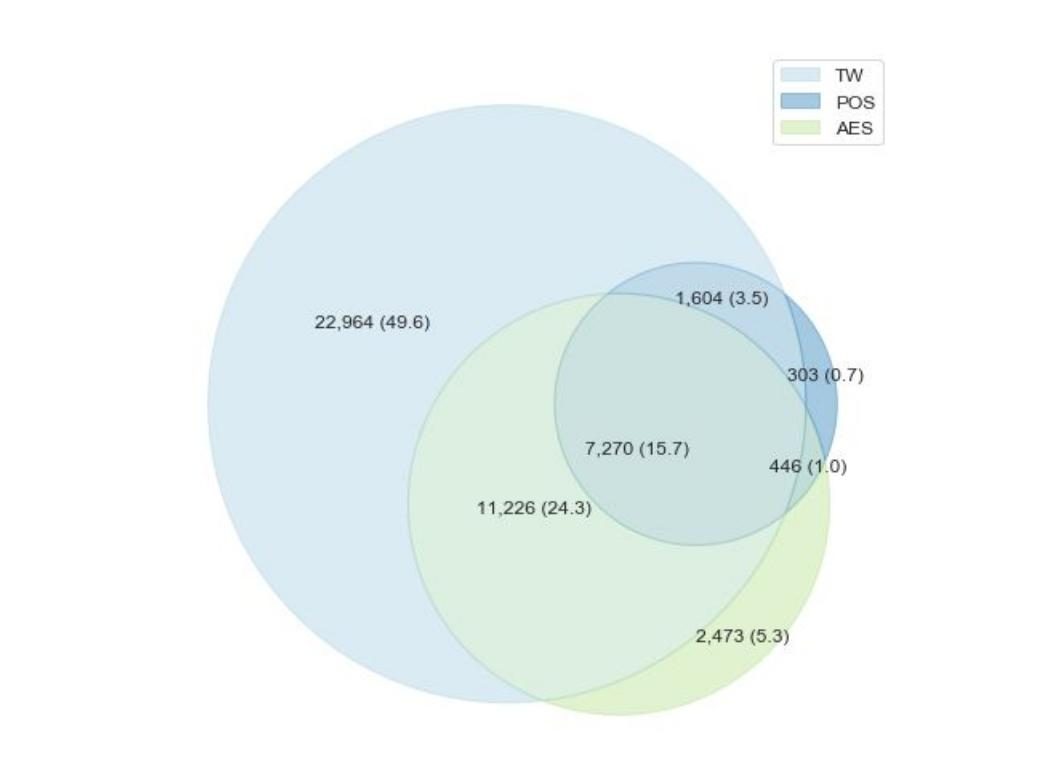

Using this approach, the team identified an additional 13,699 research articles (58.7%) not found by Altmetric’s method. In other words, although many Facebook users share research papers publicly, the majority prefer to do so in private exchanges—hidden from public view.

Even more importantly, the research papers that are shared on the platform receive almost as much engagement as those on Twitter.

“The volume of the engagement—how many times a paper is shared—is actually comparable between the two platforms,” Asura explains. “It’s fascinating; papers that receive a lot of engagement from audiences behave similarly to those on Twitter.”

Facebook users may not share quite as many academic papers as Twitter users do. But these findings suggest they’re much more interested in research than previously thought.

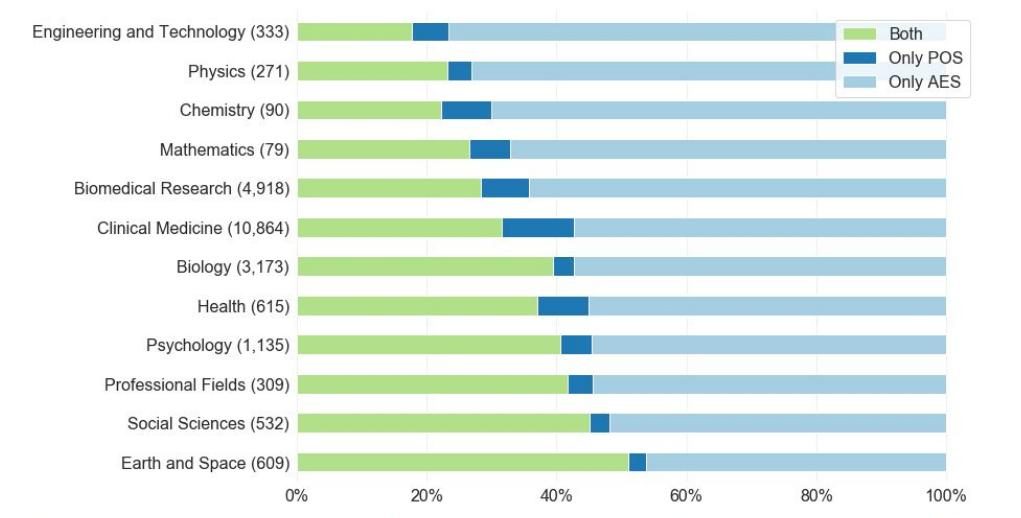

Finally, the team also found some large disciplinary differences in the data. Papers in the so-called “hard sciences” were at a greater disadvantage when measured by public posts than those in other disciplines. In other words, public shares, the most-used Facebook altmetric, seems to have a disciplinary bias:

Reimagining the future of Facebook altmetrics

What do these findings mean for the future of altmetrics research? Context, Asura says, is key.

“I can’t overemphasize how important it is to think critically about this data,” Asura says. “To consider how it applies to our work and how it impacts people outside of the Western world.”

Twitter may be the top platform for many academics, he explains. But Facebook remains one of the most important social media platforms for more than 2 billion active monthly users—especially those based in the Global South, beyond the traditional centers of knowledge production.

“Sure, looking at Facebook engagement is messy and complicated,” Asura says. “But if we truly care about the public’s interest in research, we need to look beyond that.” He continues: “It’s time we examine this platform in a more critical way.”

To find out more about the study, check out the preprint on arXiv.

Comment, reply, repeat: Engaging students with social annotation

By Alice Fleerackers, Juan Pablo Alperin, Esteban Morales, and Remi Kalir

Picture the last time you sat down to read an article for class. If your university experience was anything like most students’, chances are, you were alone.

While solitary reading has benefits and is a common aspect of learning in higher education, it may not be the most effective way to read. Research suggests that social annotation (SA) tools—which allow students to highlight and comment on digital course materials as they read—have impressive educational benefits. SA tools can help with students’ reading comprehension, peer review, motivation, attitudes toward technology, and much more.

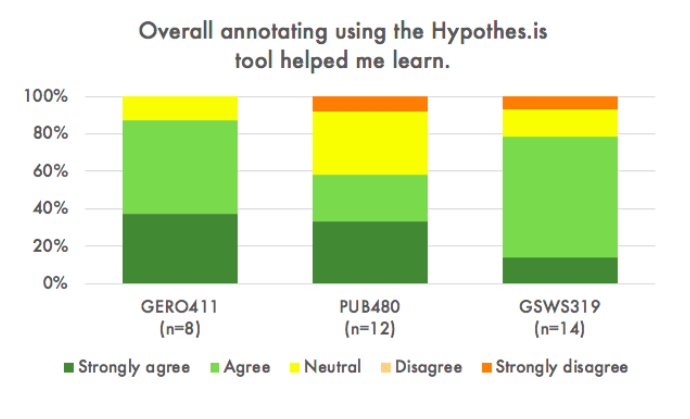

But how does SA help students learn? To find out, we introduced the SA tool Hypothesis into three different undergraduate courses at Simon Fraser University: one in Gerontology, one in Publishing, and one in Women, Sexuality & Gender Studies. Together, students created more than 2,000 annotations atop more than 250 course readings over the course of a semester—all of which we collected and coded for evidence of learning. We also asked students about their experiences with the tool in an online survey at the end of the semester; 33 students across the courses completed our survey.

The outcomes of our research were thought-provoking and inspiring—and we’re eager to publish the full results soon. But for now, we’re sharing a sneak peek of the preliminary findings, right here on the ScholCommLab blog:

Social annotation helps (most) students learn

Overall, students in all three courses agreed that Hypothesis was a useful tool for learning. More than 70% reported that it helped them learn. Over 70% said it helped them understand other points of view, and more than 65% said it encouraged them to think about the course content outside of the classroom.

“I think annotations should be incorporated into every class with weekly course readings! It ensures that students are thoroughly reading course material and coming to class with a decent understanding of the week’s material.”

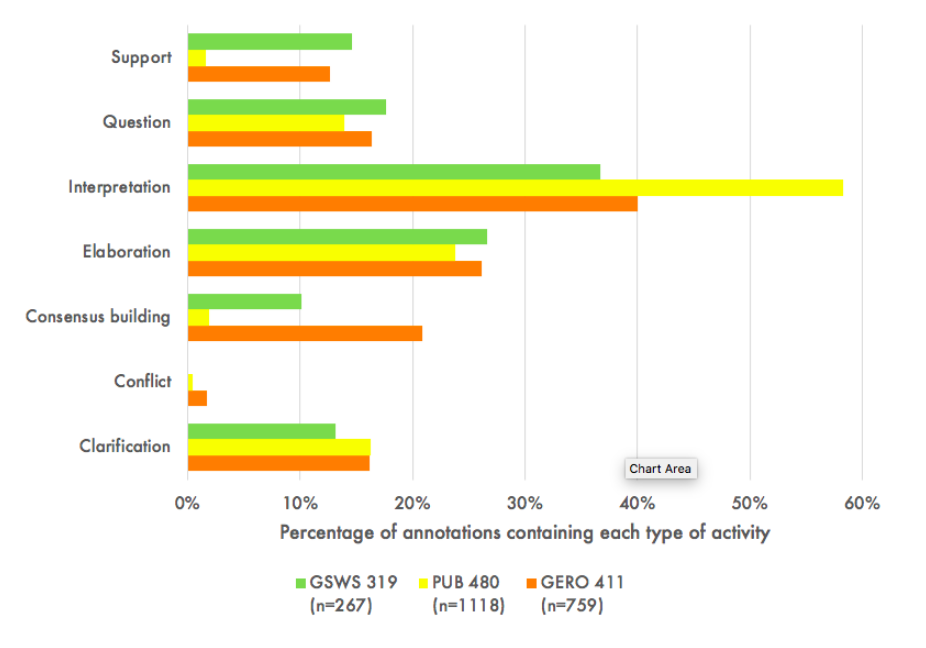

We also saw evidence of learning in the annotations themselves. When we analyzed each comment and question left by the students for different forms of learning, we found that students in all three courses relied on the tool for interpretation, using Hypothesis to draw hypotheses or conclusions, summarize information, or suggest problem solutions. Elaboration activities, like defining difficult terms or connecting ideas with examples, were also common, followed by questioning and clarifying activities.

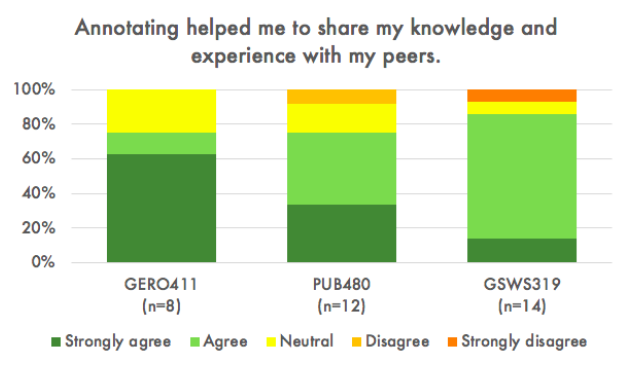

Social annotation helps students feel connected

Using Hypothesis also made it easier for students to build community within their courses. More than 60% said annotating helped them feel connected to their peers, and almost 70% said it increased the amount of interaction they had with others in the class.

These social benefits may have been especially important for shy students, as well as those for whom English was a learned language:

“I am quite introverted and shy so speaking out in class is very intimidating. Engaging with classmates online and through annotations allowed me to contribute to class discussions.”

Formal incentives inspire students to annotate

Overall, students in all three courses were positive about their experience with Hypothesis, but when asked why they annotated, students offered up a diverse array of responses. For example, some said they annotated for personal learning, using Hypothesis as a way to prepare for essays or exams. Others said they were motivated by social reasons—using annotations as a way to connect with their peers:

"I like the idea of talking with my classmates and working through ideas together. Reading multiple interpretations of different ideas also adds diversity.”

But although many students listed many different reasons for annotating, motivations like “Participation marks” or “It was required for my class” were by far the most common. No matter how much students enjoyed using Hypothesis, our results revealed that the importance of formal incentives cannot be underestimated.

The instructors who took part in this study seemed to acknowledge this, too. All three chose to incentivize annotations in some way, either by offering bonus marks for completing weekly annotations, or by using a detailed grading rubric.

How can educators use SA tools to support student learning?

So where does this leave us? Together, our results reveal that SA tools and practices can play an important role in many university courses. By creating a space for discussion within the course readings themselves, SA tools like Hypothesis can help students learn, share ideas, understand new perspectives, and feel connected with one another.

But our findings also suggest that these benefits are only possible when annotations are formally incentivized. Although students themselves acknowledge the benefits of annotating, grades and participation marks remain their top motivation for doing so. To help spark interest in annotation, instructors need to provide clear guidelines that reward high quality contributions.

For an example of how to grade social annotations, check out this marking rubric by Dr. Sharon Koehn. To find out more about this ISTLD Dewey Fellowship-funded research, sign up for the ScholCommLab’s newsletter or watch Juan Alperin's #ianno19 presentation:

Emojis in Scholarly Communication: 🔥 or 💩?

“Should there be an emoji for everything?” asked journalist Sophie Haigney in a recent New Yorker article. “What, exactly, do we want from our emojis?”

The future of the emoji may be uncertain, but one thing is abundantly clear. Emojis are booming. From classic smiley faces to dancing “party parrots,” there are now almost 3,000 options to choose from. They fill our text messages, our Slack chats, our emails—even some of our books. In 2015 the “tears of joy” emoji was declared Word of the Year by Oxford Dictionaries.

But despite the digital dominance of emojis, they haven’t infiltrated every aspect of daily life. Recent research by ScholCommLab co-director Stefanie Haustein reveals that, when it comes to scholarly communication, emojis mostly get a 👎.

Why study emojis?

Stefanie first decided to investigate emojis as part of a larger research project exploring how academic work is shared on Twitter. The goal was to understand what kinds of scientific documents are tweeted most, as well as when, how, and by whom. She hoped the emoji data would offer a more nuanced view of the academic Twittersphere.

“The idea was to capture another level of meaning and emotion in the tweets,” she explains. “Emojis are a unique form of visual communication—they have the potential to add to what’s shared through standard means, like words and hashtags, especially in short messages like tweets.”

Using data from Altmetric, she analyzed more than 40 million tweets mentioning scientific journal articles, preprints, conference proceedings, and other documents. Then, she analyzed each tweet for emojis, noting both the type and number used. Here’s what she found:

Less than 1% of scholarly tweets use emojis

Although 10-15% of academics use Twitter, only a small proportion rely on emojis. Of the 42.5 million tweets Stefanie analyzed, only 286,087—0.7%—contained at least one emoji.

| Emoji | Category | Tweets | Occurrences | Tweeted documents |

| 👍 | Liking | 15,688 | 19,018 | 5,911 |

| 👇 | Pointing | 13,432 | 20,308 | 2,426 |

| ➡️ | Pointing | 11,403 | 13,896 | 2,415 |

| ♀️ | Gender | 10,983 | 13,071 | 2,590 |

| 👉 | Pointing | 8,523 | 9,805 | 2,056 |

| 👏 | Liking | 8,459 | 16,436 | 3,265 |

| 💪 | Sports | 6,899 | 8,528 | 1,746 |

| 🔒 | Reading | 6,326 | 7,063 | 234 |

| ❤️ | Liking | 6,178 | 7,597 | 2,611 |

| 😂 | Faces | 5,505 | 10,053 | 3,006 |

| 😉 | Faces | 5,438 | 5,923 | 3,094 |

| 😀 | Faces | 5,312 | 6,222 | 2,728 |

| 😊 | Faces | 5,251 | 5,996 | 2,771 |

| ✅ | Check | 5,151 | 7,860 | 642 |

| 🔬 | Science and technology | 5,142 | 5,782 | 1,595 |

| 👌 | Liking | 4,665 | 5,511 | 1,958 |

| ☺️ | Faces | 4,628 | 4,804 | 1,277 |

| 🚀 | Science and technology | 4,285 | 4,412 | 3,470 |

| 🏋️ | Sports | 3,675 | 4,443 | 533 |

| 😳 | Faces | 3,613 | 4,953 | 1,396 |

These results are surprising, given how popular emojis are beyond the academic sphere. Researchers estimate that more than 90% of people have used emojis in some form of digital communication. On Twitter, almost 1 in 5 tweets contain at least one.

Emojis aren’t just popular; they’re also powerful. Digital marketing research has found that tweets with emojis are more than 25% more engaging than those without. Using emojis in social media can boost click-through-rates, likes, shares, and more.

“I was really taken aback by how few tweets linking to academic papers contained emojis,” Stefanie says, “It made me wonder whether academics are missing out.”

However, academics may just be late to the game: the uptake of emojis increased over the years from 0.02% in 2013 up to 1.57% in 2017 📈.

Academic emojis fall into 6 categories

The tweets that did contain emojis followed very distinct patterns. Among the 50 most tweeted emojis, most fell into one of the following six categories:

1. Faces (🤔😱😉😁)

26 of the 100 most used emojis were face-based emojis. These tweets expressed a range of emotions, likely to show the users’ personal opinion about the document they were sharing.

2. Liking (👍❤️👏)

17% of the 100 most used emojis suggested a positive judgment of some sort, usually of the scientific document being discussed.

3. Science and technology (🔬 🚀 🌏)

13 out of 100 most tweeted emojis included scientific imagery, like satellites or microscopes. These emojis were often content-specific—as when rockets appeared in tweets about astrophysics research. Other times, they played a more general role, simply highlighting the scientific nature of the tweet.

4. Signs (🔴⚠️❗)

8 out of 100 emojis were signs, which seemed intended to grab attention.

5. Pointing (👇➡️👉)

Gestures, like pointing fingers or arrows, featured in 6% of the 100 most-tweeted emojis. Many of these pointed to a link for the scientific document being mentioned.

6. Reading (👀 📚 📄)

Reading emojis, like books and documents, seemed to play a similar role as the pointing emojis. They appeared 6 out of 100 times.

Many of the top scholarly emojis overlap with those that are popular in general. But some, like the emojis in the reading and technology categories, seem to be particular to academia.

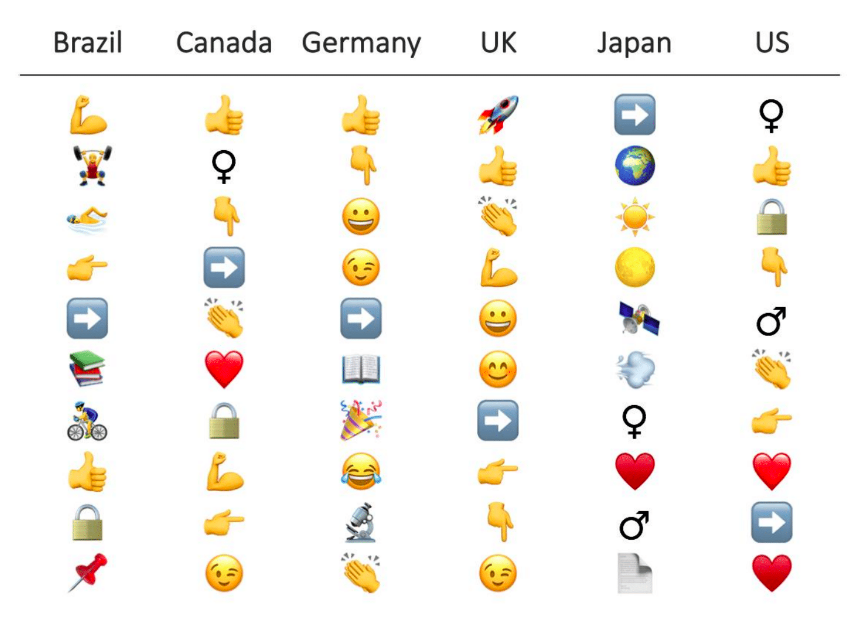

Different countries use emojis differently

In addition to these general trends, Stefanie also identified distinct patterns of emoji use between countries. That is, when sharing research findings on Twitter, users from Brazil or Germany favoured different emojis than those from Japan or Canada, for example.

Here are the top 10 emojis used by Brazil, Canada, Germany, the UK, Japan, and the US:

Although it’s not possible to draw firm conclusions about these differences, these results do raise interesting questions. For example, does the popularity of the lock emoji (🔒) in Brazil, Canada, and the US suggest that conversations about paywalls and Open Access are front-of-mind for these countries? Are questions about gender issues (♀️ and ♂️) more common in nations like Japan, Canada, and the US than in others?

Exploring these questions is a task for future research. But, for now, these findings offer a more nuanced understanding of emoji-based communication in the scholarly sphere.

“It was fascinating to see how each country used emojis differently,” Stefanie says. “No two were the same.”

Emojis may be a ‘universal language’, but it seems to be spoken with a wide range of accents, dialects, and expressions.

To find out more about the project, check out Stefanie Haustein’s book chapter on Scholarly Twitter Metrics, available as a preprint at arXiv.org.

FSCI2019 | A deep dive into scholarly communication

Each year in August, researchers, librarians, educators, students, and open access advocates gather together for the FORCE11 Scholarly Communication Institute (“FSCI”)—a jam-packed week of learning, discussion, and celebration of all aspects of scholarly communication. This year, I was lucky enough to be one of them—thanks to a generous travel scholarship. The experience was one I’ll never forget.

Over the course of the week, I had the chance to learn from an incredible community of people. I heard from librarians, publishers, and researchers about their changing role within scholarly communication and the challenges and opportunities that come with it. I gained perspectives from Mexico, Japan, Sudan, and beyond about the unique state of scholarly communication in each of these nations. I took part in conversations about open knowledge, open pedagogy, and open culture, as well as the many different forms these ideas can take.

I left FSCI2019 with many answers, but also with many questions. I’m summarizing just a few of them here for those who couldn’t attend in person:

Is “access” to knowledge enough?

What audiences are overlooked by ‘traditional’ scholarly publishing models? Does making research available actually make it accessible? And how do factors like geography, culture, infrastructure, and education influence who has access to knowledge and who doesn’t?

These questions came up again and again in all of my courses, as well as in many of the lightning talks and plenaries. Presenters highlighted the importance of offering educational materials in multiple languages, depositing publications in open repositories, writing for non-academic audiences, and more.

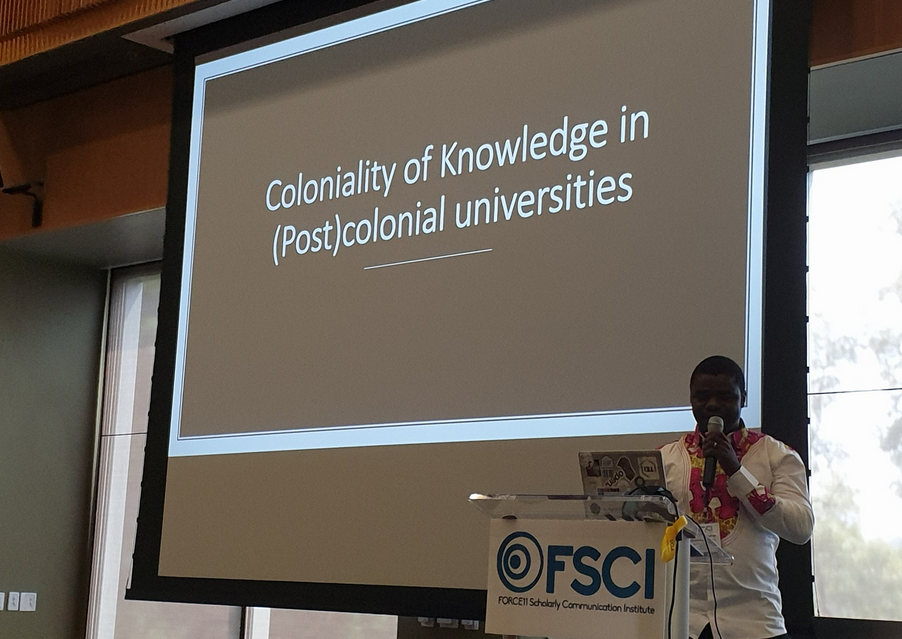

But what struck me most was Thomas Hervé Mboa Nkoudou’s plenary keynote, "Scholarly Communication reimagined from Post Colonies." During the talk (and, later, in his class on the same subject), he emphasized how contemporary academic publishing keeps researchers in the so-called ‘Global South’ at the periphery of research production. Highlighting the colonial nature of scholarly communication, he pushed us all to reconsider our own roles as producers, consumers, and disseminators of knowledge:

"We should explore alternative ways for communicating research, aside from a traditional, published journal article." —Thomas Hervé Mboa Nkoudou

What does the scholarly future look like?

The changes undergoing academic publishing were another key topic of conversation at FSCI this year. Should we ‘open’ up the peer review process or abandon it entirely? Is the preprint a viable alternative to a scholarly journal article? How do traditional publishing frameworks disadvantage early career researchers?

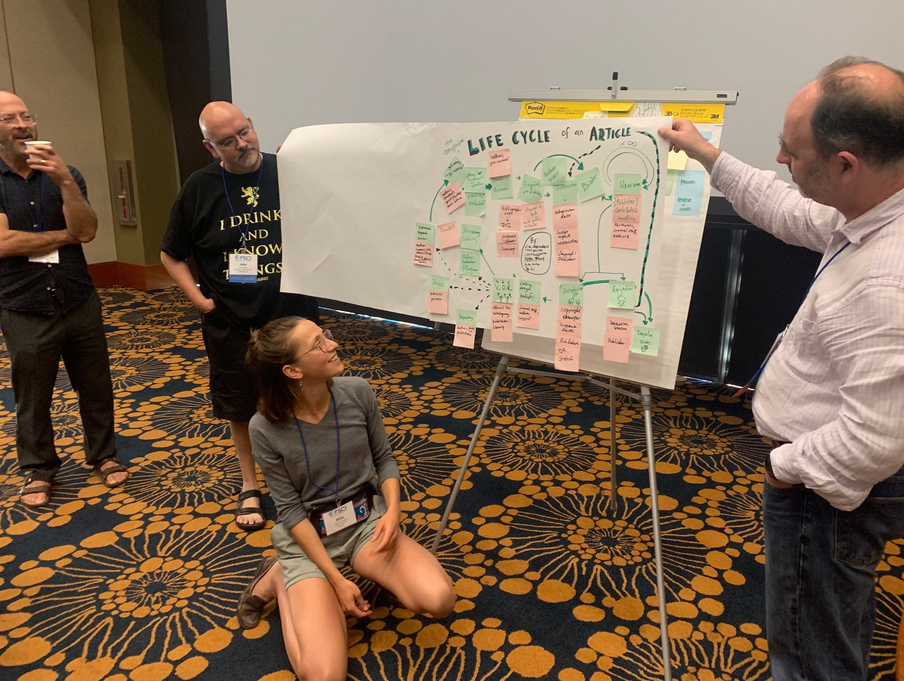

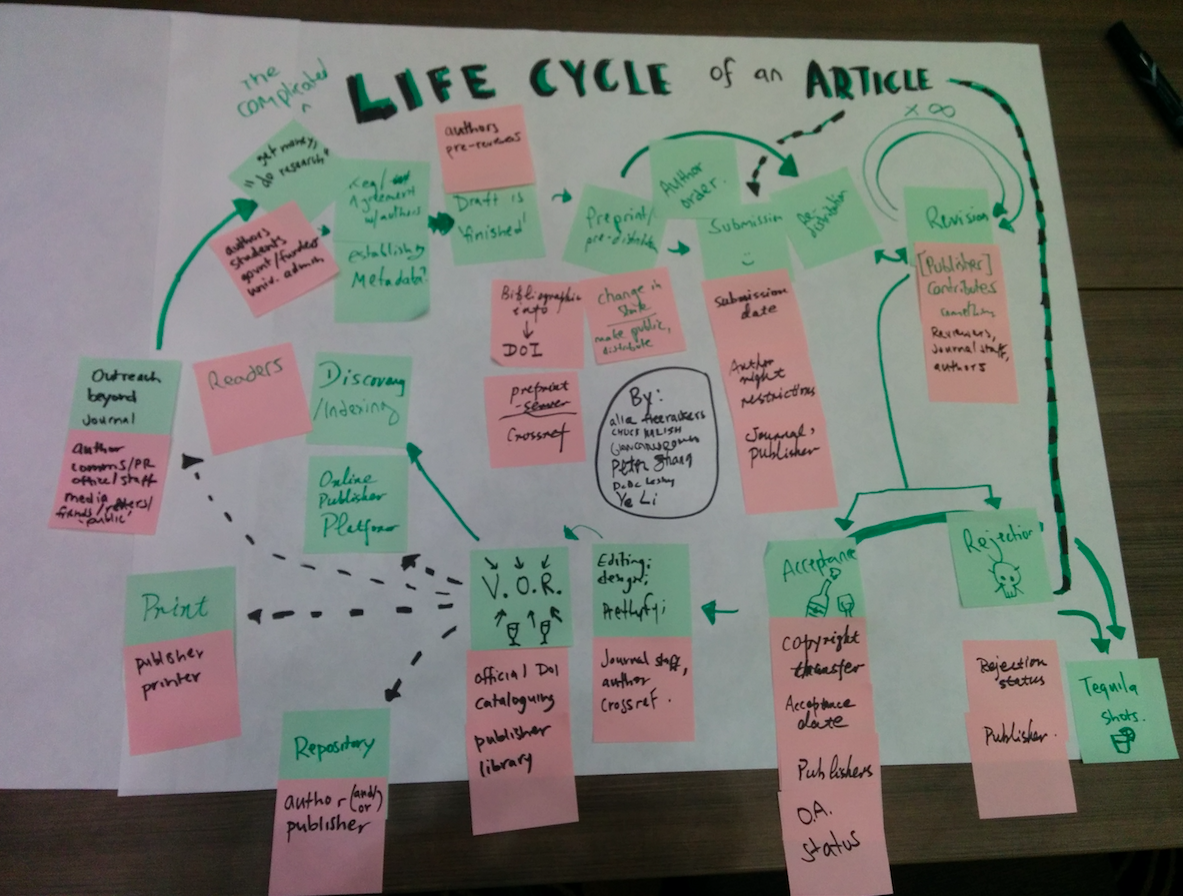

Questions such as these sparked fascinating conversations, especially in Cameron Neylon and Nicky Agate’s course, Inside Scholarly Communication Today. Through hands-on activities and lots of group discussion, we dug deep into the current nature of scholarly publishing—and brainstormed some creative ways it could be improved.

Can we build a scholarly communication system on collaboration, rather than competition?

How did a system meant to encourage sharing and collaboration become obsessed with maintaining power and prestige? Is a more open, inclusive approach to scholarly communication even possible? What would that mean for science—not to mention society?

From the classroom to the dinner hall, countless conversations centered on the rivalry that permeates so much of academic life. We discussed everything from peer-review sabotage to scholarly superiority complexes, brainstorming ways to prevent them. We daydreamed about the possibility of creating a more “generous” academic system—one built on trust and mutual support, rather than competition.

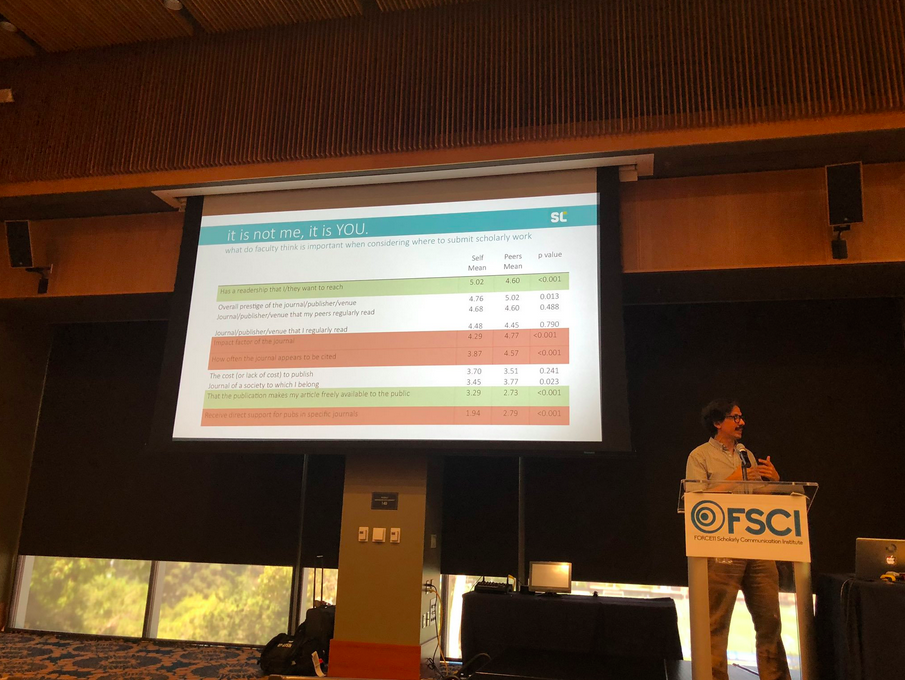

The final talk of the week—by the ScholCommLab’s own Juan Pablo Alperin—ended these conversations on a more positive note. Citing recent research about how faculty perceive their professional futures, he shared that many academics really do value openness, but feel pressured to pursue prestige-oriented publishing strategies because of what they think their peers value. This research wasn’t new to me, but I saw it in a new light after everything we’d covered during the previous sessions.

“No problem is too big, but every problem is too big if you constrain how you think”— Anita Bandrowski

As we wrapped up the closing remarks, I was reminded of something Anita Bandrowski said during one of the earlier presentations: “No problem is too big, but every problem is too big if you constrain how you think.” When it comes to changing our academic system, we still have a long way to go. But if we can address our misconceptions and be honest about what we truly value, change really is possible.

Find out more about the FORCE11 Scholarly Communication Institute on their website.

Publish or perish? Faculty publishing decisions and the RPT process

By Meredith T. Niles, Lesley Schimanski, Erin McKiernan, and Juan Pablo Alperin – with Alice Fleerackers

As tenured faculty positions become increasingly competitive, the pressure to publish—especially in “high impact” journals—has never been greater. As a result, many of today’s academics believe having a strong publication record is necessary for the review, promotion, and tenure (RPT) process. Publishing, for some, has become synonymous with professional success.

Yet little is known about academics’ perceptions of the RPT process and how they influence their publishing decisions. What research outputs do faculty believe are valued in RPT decisions? How do these beliefs affect where and what they publish?

To find out, we surveyed faculty of 55 academic institutions across the US and Canada, asking them about their own publishing priorities and those of their peers, as well as their perceptions importance within review, promotion, and tenure. Here’s what we found:

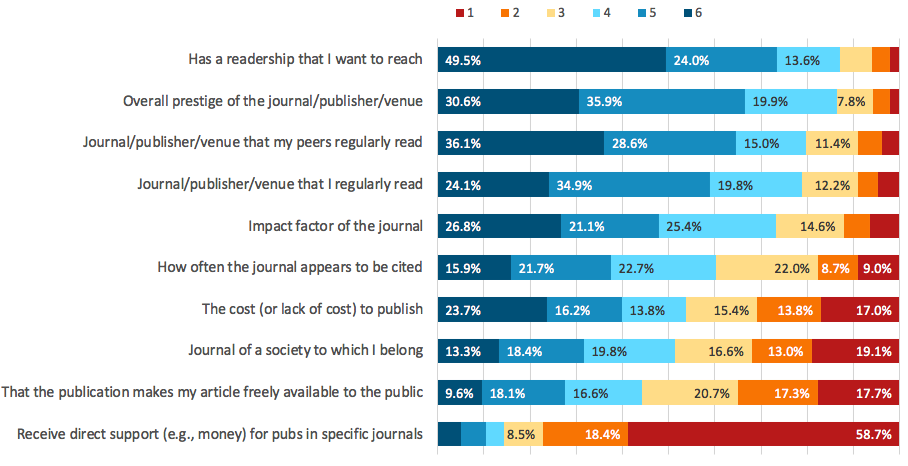

Faculty prioritize journal readership in publishing decisions...

When it comes to deciding where to publish their work, academics reported valuing journal audience above all other factors. The top three factors they identified were:

- Whether the journal had a readership they wanted to reach

- The overall prestige of the journal

- Whether the journal was regularly read by their peers

Of course, other factors, like the journal’s impact factor (JIF) or the fees associated with publication, were still important to many faculty, but to a lesser degree than readership:

Importantly, we saw some significant demographic differences among faculty in their publishing priorities. Non-tenured respondents—who are under greater pressure to perform than tenured faculty—placed higher importance on the JIF, for example. Younger faculty were also more likely to prioritize factors like journal citation frequency and journal prestige, compared to older, more established peers.

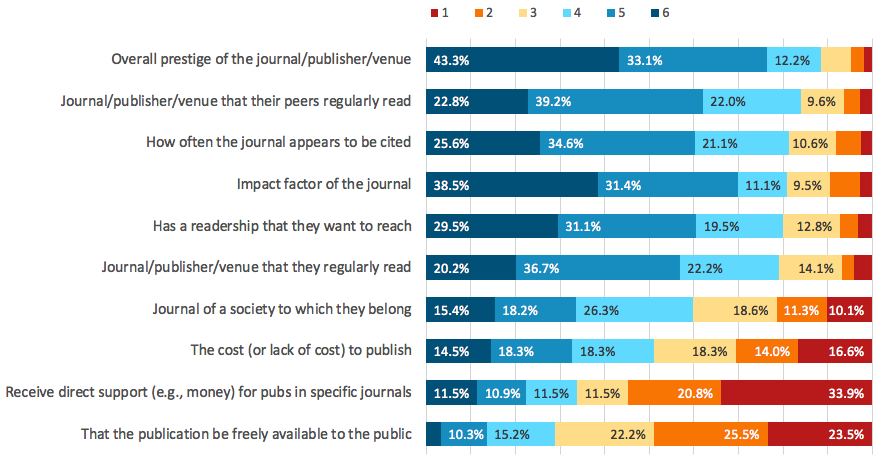

...but faculty believe their peers value prestige above all else.

When it came to evaluating others’ publishing priorities, however, faculty responded quite differently. They believed their peers would be more likely to value factors like journal prestige and JIF when deciding where to publish their work. They also believed their peers would be less likely to make decisions based on the journal’s readership or open access status:

This sense of illusory superiority when comparing oneself to peers is nothing new, but it was interesting to see it come into play in our survey.

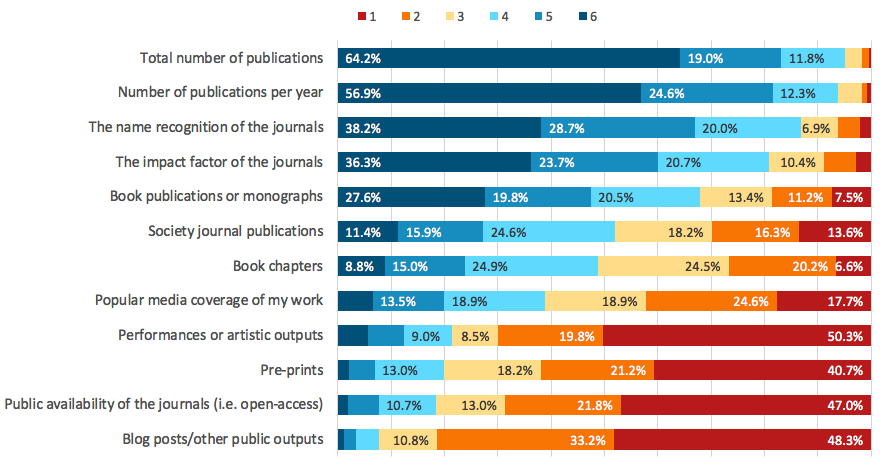

Academics see publication quantity and journal reputation as top factors in RPT decisions

Next, we asked faculty what factors they believed were valued most during the RPT process. We found a notable disjoint between their own publishing priorities and what they felt would benefit their careers.

Faculty identified the following three factors as being most important for RPT decisions:

- Total number of publications

- Number of publications per year

- Journal name recognition

Again, there were important demographic differences among faculty, with older, tenured respondents—those most likely to serve on RPT committees—being were less likely to value journal prestige and publishing metrics, compared to untenured respondents.

Faculty’s beliefs about the RPT process are key to their publishing decisions

Finally, we explored how academics’ perceptions of the RPT process affected their own publishing priorities through a series of models. In short, we found that these perceptions of what is valued by the RPT process were more likely to predict publication decisions than age, gender, or publication history.

Conclusion

Together, these results paint a complex picture of the pressures faculty face when deciding where to publish their work. On the one hand, most academics value the readership of a journal over its citation metrics. Yet, this value is at odds with the factors they believe will help them succeed in the RPT process—publication quantity and journal reputation—even though tenured faculty and those often on RPT committees didn’t value these factors as highly. Adding to this are the disjoints between faculty’s own publishing priorities and how they perceive those of their peers. Such disjoints highlight clear pathways for conversation in academia about what is most valued by communities for their scholarship, conversations we hope this work can help facilitate.

The results of this survey build on previous work examining the role of public scholarship and the journal impact factor in RPT documents. Read the full preprint at bioRxiv, or find out more about the RPT Project on the scholcommlab website.

To preprint or not to preprint? Research for a more transparent publishing system

"Academic life" by uonottingham is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

“For researchers, there is immense pressure to publish in journals that are highly competitive,” says Naomi Penfold, associate director of the scientist-driven nonprofit ASAPbio. “[This, in turn,] means that the process of sharing what you have found, evaluating whether claims are valid or not, and gaining recognition and visibility is all wrapped up in the long, arduous, and mostly opaque process of publishing at these few journals.”

Improving this “long, arduous” process is core to ASAPbio’s mission of advancing “innovation and transparency in life sciences communication.” It’s also the focus of a new research collaboration between ASAPbio and the ScholCommLab exploring the status of preprint adoption and impact in different research communities.

In this post, we’re shining a spotlight on the Preprints Uptake and Use research team, and offering a glimpse of their findings so far.

Why study preprints?

Academic peer review is often seen as a cornerstone of science, and remains one of the most trusted ways of assessing research quality. But despite its status within academia, there’s little evidence of its effectiveness. (In fact, some research suggests peer review may actually prevent high quality science from becoming published).

Whether or not this is the case is still unclear, but scholars are exploring new avenues for disseminating their work. Preprinting—openly publishing research findings before submitting them for peer review—is one such avenue. By allowing researchers to circumvent the lengthy peer review process, preprints have the potential to catalyze research collaboration and innovation—months before the final journal article is published.

“I see preprints as an online-first tool that allows anyone to discuss the latest findings while they're still fresh”—Naomi Penfold

“I see preprints as an online-first tool that allows anyone to discuss the latest findings while they're still fresh,” says Naomi. “Preprints could help increase the likelihood and speed that science is seen, understood, tested, and built upon, which would be beneficial for individual researchers and society at large.”

But despite these potential benefits and substantial growth in preprinting in the past few years, little is known about the use of preprints in individual academic communities. While we can track preprint numbers in major subject categories and on individual servers, we currently do not have data to understand who is preprinting and whether there are nuances between individual research communities: Which researchers preprint more than others in their network? In which research fields is preprinting growing in popularity, and in which fields is adoption disproportionately low? These are just some of the questions that the Preprints Uptake and Use research team is exploring this summer—questions that could help inform efforts to raise awareness of preprinting and measure their impact on science.

Meet the Preprints Team: Mario Malički and Janina Sarol

The ScholCommLab preprints team is comprised of two visiting scholars: Mario Malički and Janina Sarol. A recent postdoc at AMC and ASUS Amsterdam, Mario has been researching the role of journals in fostering responsible research conduct since 2017. Janina is a PhD student in Informatics at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign with a background in Computer Science and Information Management. Together, they bring a unique mix of skills and interests to the research team.

“I used to work at the university library back in Illinois,” Janina says, when asked how she first became interested in preprints. “I was transforming all of their collections into linked data, and I was surprised by how much dirty data there was.” There were so many authors and contributors, so many different articles and journals. Determining who had published what and where, she explains, turned out to be no small feat.

While others may have been frustrated by the messiness of bibliometric data, Janina was fascinated by it. “That’s what interested me,” she says, “trying to clean the data, so that we could do a better analysis.” She smiles, “Bibliometrics is like a library. All of the books seem to be stacked in the right place. But, when you dig deeper, things are not always so neat. “

“Bibliometrics is like a library. All of the books seem to be stacked in the right place. But, when you dig deeper, things are not always so neat. “ — Janina Sarol

Like Janina, Mario’s interest in scholarly publishing began when he discovered how flawed the system could be. It was 2011, and he had taken a step back from medical school to join the research department at the University of Split. He was working under the supervision of the editors of Croatian Medical Journal, the country’s top medical publication.

“They experienced a lot of people trying to bribe them to get into the journal,” he explains. “In most Croatian universities at the time, you needed at least one publication in a journal with an impact factor higher than 1 to get your PhD,” he continues. “In a country as small as ours, there was only one such journal—and that was theirs.”

Witnessing these informal pressures firsthand sparked a deep interest in how the process of authorship works—and how it could be improved. He dove into the world of meta-research, balancing his teaching responsibilities with this new passion. “I completely fell in love with meta-research,” he says, “I realized that I would never go back to the hospital.”

“I completely fell in love with meta-research, and realized that I would never go back to the hospital.” — Mario Malički

A messy today and a bright tomorrow

For the last month, Mario and Janina have been working under the supervision of ScholCommLab co-director Juan Pablo Alperin to collect, consolidate, and analyze data from more than 60 different preprint servers. Eventually, they hope to use the data to answer such questions as:

- How quickly do individual preprint servers develop?

- Who publishes preprints and how often?

- Do disciplinary or geographical factors influence preprint uptake or use?

- Are the preprints in any way different from the published papers?

- How many preprints end up being published?

But first, the team has to clean the data—a task, it turns out, that’s more complex than expected.

“The most striking thing about the project so far is that we had to go through each aspect of the metadata we were trying to collect—author, date, subject—and ask, ‘Can we trust this or not?’” Janina explains. “For most things, the answer was, no.”

The data the team has analyzed so far is so riddled with missing metadata, duplicate entries, and conflicting information that excluding problematic entries simply isn’t possible. “We’re not talking about 10, 20, or 30 records with errors,” Mario explains. “We’re talking about 1,000 records. If you exclude those, it’s ridiculous.”

But although the messy data poses challenges for Mario and Janina’s study, it also raises important questions for the future of preprints research.

“I think people presume that, because the data is out there, it’s correct... We’re hoping that, after this, people will be a bit more aware that you just can’t trust those numbers.” — Mario Malički

“I think people presume that, because the data is out there, it’s correct,” says Mario. “But preprint servers don’t always have checks in place in the same way that journals do. We’re hoping that, after this, people will be a bit more aware that you just can’t trust those numbers.”

Despite the setbacks, the team is optimistic about the future. They’re still plugging away at the data, and are in touch with some of the preprint servers with suggestions for how to improve their metadata systems.

“We’re excited to start analyzing the data,” says Janina. “If all goes well, we’ll be publishing a preprint of our own soon.”

To stay up to date about the Preprints Uptake and Use project, visit the ScholCommLab’s website or sign up for our newsletter.

Academic review promotion and tenure documents promote a view of open access that is at odds with the wider academic community

By Juan Pablo Alperin, Esteban Morales and Erin McKiernan. First published on the LSE Impact Blog on July 17, 2019.

The language of Open Access (OA) is littered with so many colours, metals, and precious stones, that you would be forgiven for losing track. The proliferation of these “flavours” of OA has been a useful analytical tool for those that study scholarly communication, but it has also complicated the discussion about what academics can do to realise the “unprecedented public good” of opening access to research that was at the heart of the Budapest Open Access Initiative.

Whilst those steeped in discussions about OA might be concerned about new economic models and the lack of clear licensing of much OA content (“bronze OA”), how do faculty from across the disciplines actually define OA? Do these definitions even matter to those outside of scholarly communication circles? Evidence we have gathered as part of a project to study incentives in academia suggests they do.

In a recent study, analysing documents related to the review, promotion, and tenure (RPT) process at a representative set of 129 universities from the United States and Canada, only 5% of institutions mentioned Open Access. Just as fascinating as this lack of interest and support for making research OA, however, were the misconceptions we found surrounding the term itself. For example one document cautioned faculty against “publishing in journals that are widely considered to be predatory open access journals”. Others equated OA with materials that are “self-published, inadequately refereed, open-access writing.”

Given that the documents that govern the RPT process embed these misconceptions and false associations, we wanted to know how faculty themselves thought about OA. Do faculty commonly associate OA with low-quality, non-refereed, predatory content?

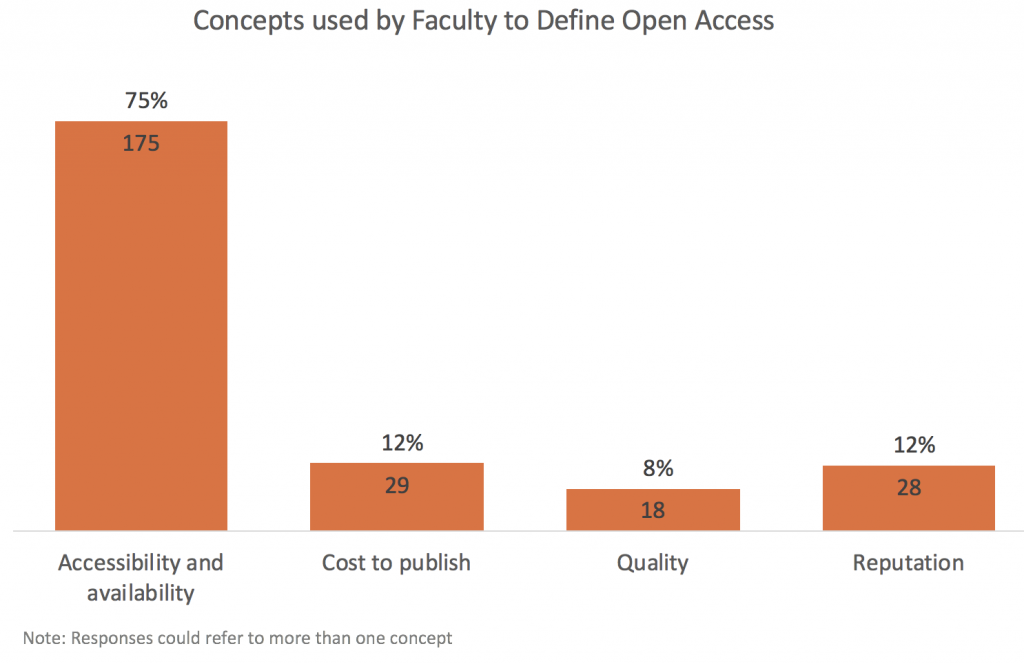

To answer this question, we surveyed faculty at 60 of the institutions from our sample about their perceptions of the RPT process, including an open-ended question asking them to define, in their own words, the term “Open Access.” We received 234 responses to this question, which we analyzed using open-coding and constant comparison. Our results show that faculty tend to define OA along four key axes: (1) Accessibility and Availability, (2) Cost to Publish, (3) Quality, and (4) Reputation. A distribution of how many responses fell in each category can be seen below.

Accessibility and Availability

The frequencies of the responses were encouraging: 70% of faculty defined OA by the ease with which a journal and its articles can be accessed by readers, including how much they have to pay (i.e., free). They define OA with phrases like “…accessible to all, free, on-line”, “do not need to pay to access journal articles” and, our personal favourite, “Can post link to Facebook, my mom can read it.”

Cost to Publish

At the same time, 12% of the respondents equated OA with an “author-pays” model. In defining OA, faculty responded by saying that OA is “Expensive for academics” or that OA means that one “Must pay to publish.” This conflation is not uncommon, both among academics and in the popular press. Although the author-pays model has been successful at growing OA, and has become the focus of some efforts to “flip” journals to OA (like OA2020 and Plan S), the majority of OA journals registered in the DOAJ do not follow this model, and increasingly groups are standing up against it.

Quality and Reputation

Other definitions expressed concerns about the quality and reputation of OA publications, which featured in 7% and 11% of definitions, respectively. Respondents defined OA with phrases like “often not the highest-quality” and “not always respected.” Such concerns about quality have surfaced in previous faculty surveys, and often stem from a misconception that OA journals have less rigorous peer review processes, despite evidence to the contrary and the transparent peer review in place at many OA journals.

Conclusions

Overall, the results of our survey give reason to be optimistic: the majority of faculty understand that OA is about making research accessible and available. However, they also point to persistent misconceptions about OA, like necessarily high costs and low quality. This raises questions: How might these misconceptions be affecting RPT evaluations? How should researchers who want to prioritise the public availability of their work guard against the potential that their peers hold one of these negative associations? And, as a community, how can we better communicate the complexities of OA without further diluting the central message of open access? Perhaps we can begin by adequately representing and incentivising the basic principles of openness in our RPT documents.

The findings and views presented here are the collective effort of the whole Review, Promotion and Tenure team at the Scholarly Communications Lab, including the authors of this blog post listed above, Dr. Lesley Schimanski (Simon Fraser University), Dr. Meredith Niles (University of Vermont), and Ms. Michelle La (Simon Fraser University).

ScholCommLab goes bowling!

This week, the Vancouver ScholCommLab packed things in early and hit the bowling lanes. Team bonding, apparently, is best achieved by participating in competitive individual "sports."

Each of us had their own unique strategic, from granny-style bowling to a carefully orchestrated gutter-bounce approach. We had a great time—and learned some important things along the way:

- For some reason, bowling involves only five pins in Canada (our international lab members are appalled.)

- Juan's Twitter handle was inspired by his bowling nickname... and not the other way around.

- We are far better researchers than we are bowlers—at least, we hope so!

We finished up the night with some good food, music, and, of course, a bunch of big smiles.

Meet the reverse flip journal: Q&A with Lisa Matthias

It all started with a tweet.

Scholarly communications analyst Najko Jahn was exploring the library catalogues of Springer Nature when he stumbled across something he hadn’t noticed before. A number of journals that had once been Open Access…. suddenly, weren’t.

He tweeted about the strange phenomenon, to which Open Access researcher Mikael Laakso quickly replied that he’d love to do a project on this, and would anyone be up for it? Within an hour, ScholCommLab visiting scholar Lisa Matthias had hopped on board, and the beginnings of a study were born.

Over the following months, the team scoured the web for examples of journals that had reverted from open to closed access. How common were these journals? And what could we learn from them? They uncovered some surprising results, all of which are available in a recently published paper in Publications.

In this Q&A, Matthias tells us more about these “reverse-flip” journals, and what they could mean for the future of Open Access.

Tell me about your paper. What did you find?

We live in a very complicated and exciting time for scholarly publishing, with the advent of Open Access changing the way in which we communicate research all around the world. However, we really don’t know much about some critical parts of this transition. So, Najko, Mikael, and I decided to explore one largely overlooked part of this: Open Access journals that have “reverse flipped,” or, flipped back to a closed access model. Some of these journals have flipped to a completely closed and subscription-based model. Others have switched to a hybrid publishing model, where the journal as a whole remains closed, but authors have the choice to make individual articles available through Open Access. We found 152 of these reverse-flipped cases in the last 13 years.

Were you surprised by how many reverse flips you found?

Yes? No? Both? I don’t like to presuppose what data will look like before gathering it. After scouring the data sources to see what we could find, we realized this was phenomenon is happening at a bigger scale than perhaps anyone had noticed before.

I think I was mostly shocked to see how many of these journals currently operate on a hybrid model. When they first flipped, the split was 50/50. Fifty percent of the journals flipped to a purely subscription model, and fifty to a hybrid.

Eventually, hybrid became the preferred reverse-flip option. Currently, around 80 percent of the journals in our study operate on a hybrid model.

Did you see any other trends over time?

There was a big spike in reverse flips in 2013, when hybrid OA started to become more prominent. Some funders and academic institutions started covering OA charges at that time, including hybrid OA, in their funding agreements and, more recently, as part of “OA Big Deals”. These agreements were intended to be a transitional mechanism towards full OA. But what becomes clear from the overwhelming complexity of the current scholarly publishing landscape is that many publishers have struggled to keep up with the demanding pace of this transition.

What else do you know about these journals?

We looked at a lot of factors in our study, including publisher, geographic region, subject area, and more. But one of the most interesting things was the initial OA status of the journals.

More than 60 percent of the reverse-flip journals we studied originally started as subscription-based journals. That means they went through a three-stage transformation: from closed to open to closed.

More than 60 percent of the reverse-flip journals we studied originally started as subscription-based journals. That means they went through a three-stage transformation: from closed to open to closed.

Lisa Matthias

It is difficult to try and guess exactly what this means. However, what it does tell us is that the motivations of these journals, for one reason or another, is at tension with a progressive transition to an OA system. For example, some journals might struggle again to maintain their financial sustainability or independence within a marketplace that is currently biased against smaller or lesser-known journals.

So it’s all about money?

Journals got 99 problems, and money is one. But it’s not everything.

We know that a journal’s first decade is its most vulnerable, as they have to compete in the prestige game in order to survive. So if sustainability was the only factor that influenced flipping, we would have expected to see a lot of the younger journals making the switch. But we found that reverse flips occurred most often in journals that were 15 years or older. Moving back to closed access seems to be more than just a survival mechanism. Possible other reasons might include the journal’s desire for greater reach and/or internationalization. We will never really know what the true motivations are unless we actually ask the journals, though.

What do you think we could do to prevent these sorts of reverse-flips from happening in the future?

That’s a good question. Well, there are a few things—there are so many levels to this question!

First we need high quality, sustainable, manageable infrastructure for Open Access journals to function. Then we need people—preferably scholars—to run these journals. This will help to keep control within the scholarly community, and hopefully also keep costs lower.

One of the most important things is for academics to move away from this prestige economy of chasing impact factors, so that other journals can survive too.

Lisa Matthias

But I think one of the most important things is for academics to move away from this prestige economy of chasing impact factors, so that other journals can survive too. This seems to be the most important challenge in scholarly communication that we face at this time.

Your title sounds rather familiar. Have I heard it somewhere before?

Funny you should ask. It incorporates lyrics from a Missy Elliott song!

We were looking for a title—we’d left it to the last minute. Mikael had some great ideas, but then I came in…

So Missy has finally found her place in academia?

Yeah! We even tagged her on Twitter, mentioning that we used her lyrics. But Missy has not responded yet.

For more, check out the full paper, available (Open Access) from Publications.